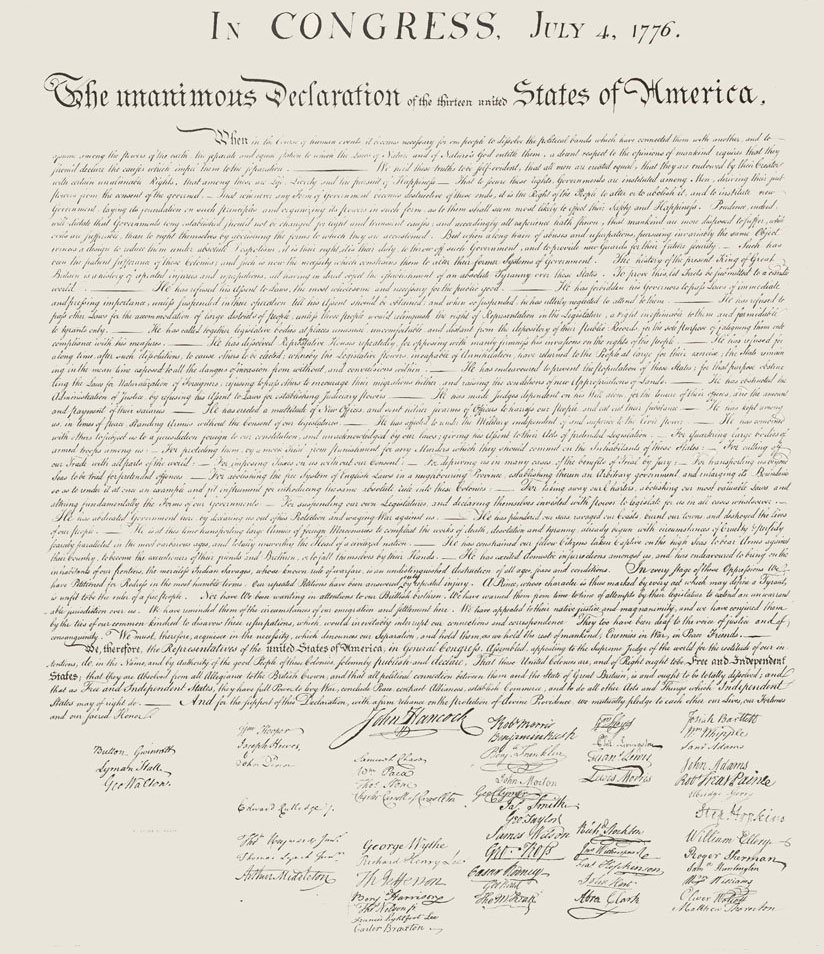

While celebrating this holiday weekend, with parades, barbecues and fireworks, take some time to reacquaint yourself with the reason we celebrate Independence Day on the fourth of July — the Declaration of Independence.

More than any other single document, the Declaration of Independence explains what it means to be an American. Uniquely among the nations of the world, Americans at our best define ourselves not by race, or blood, or language, or religion, but by our collective dedication to the political philosophy of natural rights and democratic self-government laid out in the Declaration.

To be an American is to join wholeheartedly with the “we,” who in Thomas Jefferson’s magnificent words, “hold these truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” We hold, further, “that to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed.”

The American creed is simple, but revolutionary: The people do not exist to serve some king or titled aristocrats or entitled bureaucrats.

Government exists to serve the people by securing our rights, which means that its role, though essential, is limited.

Government does not exist to promise us happiness, but only to provide us the freedom and security required for the pursuit of happiness. And government has no natural or divinely ordained authority: all its power comes from us, from our consent.

The last element of our national creed follows from the first two, and it is the crucial premise in the Declaration’s argument for American independence.

We hold “that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government” in its place. In other words, when a government systematically violates the people’s rights and the people withdraw their consent to its authority, the government loses its claim on our obedience, and the people gain the right to establish a new government, by revolutionary means if need be.

Jefferson hastens to add that revolution is a last resort, but he proceeds to make the case that King George and the British Parliament have repeatedly and deliberately violated the colonists’ rights and have so dramatically demonstrated their contempt for the people’s wishes that political independence and a war to win it are justified.

The list of grievances against the British — there are 27 in all — comprises the bulk of the Declaration. They are best appreciated by reading them aloud to a crowd of your friends and acquaintances at your Fourth of July party who, after a few beers and a couple of hot dogs, will holler and cheer at all the right moments.

If you aren’t ready to join in sprit with our revolutionary ancestors when you read (or hear proclaimed aloud) that the King is “transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to complete the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages,” you might as well call yourself a Loyalist and emigrate to Canada.

The grievances make for spirited and fun reading for us today, because the governments our forebears established after declaring independence have done such a good job of living up to the ideals of the American political creed. Today they read as a sort of anti-Bill of Rights, a list of political wrongs our founders specifically forbade our governments from perpetrating.

But we must remember that, for those early Patriots, the war for independence was as desperate and dangerous as are today’s popular uprisings against the tyrants of Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, Syria and elsewhere.

When the signers of the Declaration mutually pledged to each other their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor, they were in deadly earnest. Several of them lost everything they owned in the war, and a few lost their lives; all shared the terrible risks of waging what their enemy the King regarded as a treasonous war of rebellion.

We, however, remember them as heroes. The least we can do to honor them is to remind ourselves of the ideals for which they fought and which remain, today, the foundation of our republic.

Joseph R. Reisert is associate professor of American constitutional law and chairman of the department of government at Colby College in Waterville.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.