MANCHESTER — John Babb looks at the computer screen at his desk as numbers bounce up and down with the constant stream of information from Wall Street.

On this day, crude oil is up to $3.82 per gallon and gasoline and heating oil prices have responded with a 10-cent increase. An increase like that would have been unthinkable less than decade ago, but now the only thing stable about the price of oil is its volatility.

“A few years ago, if there was a change of 1 or 2 cents, I was holding trucks knowing prices were going down for the evening or sending trucks out knowing they were going up,” Babb said. “People call and ask for prices now. If they don’t like them, I suggest they try calling back in an hour or two. It’s day to day now. It’s hour to hour.”

After holding steady in the 80- to 90-cent range for much of the 1990s, oil prices began to rise in 2000. Prices, particularly in the last few years, have been prone to sudden and dramatic swings; but they have generally trended upward over the last decade.

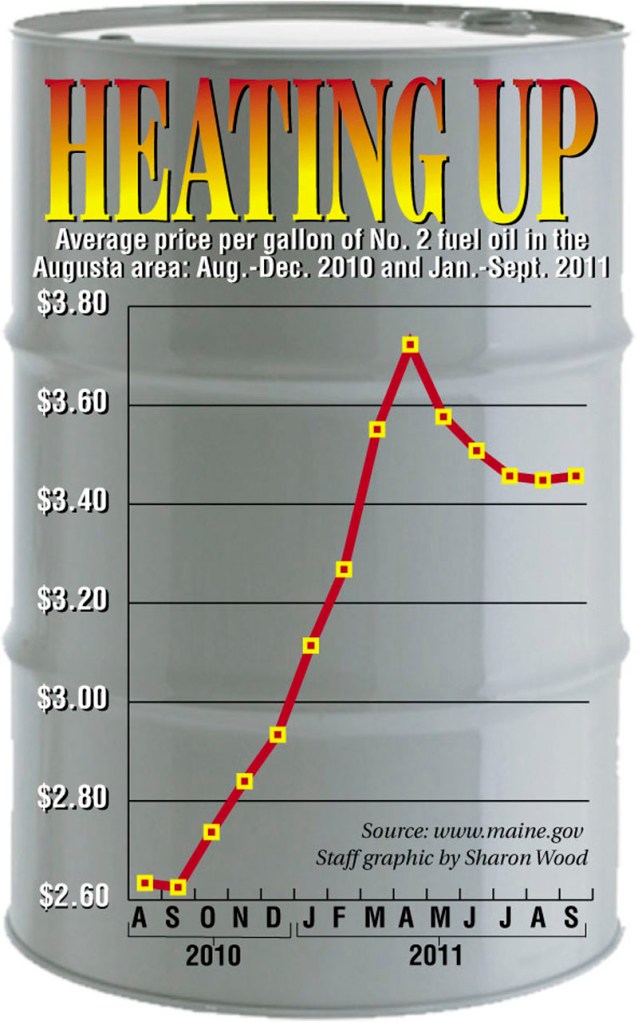

The national average for home heating oil in January 2000 was $1.48 per gallon, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. By January 2008 that number had risen to $3.36 per gallon. Prices fell back to $3.10 per gallon by January this year.

The national average on Nov. 21 was $3.93 per gallon; in Maine, it was $3.75.

The causes behind the increases are as variable as the prices themselves, ranging from natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina in 2005 to ongoing unrest in the Middle East.

Babb thinks oil prices can be traced to three main culprits: speculation in the stock market, overproduction of U.S. currency and U.S. energy policies.

Speculation

Oil prices in the 1990s were kept in check because the commodities markets were regulated, Babb said. People who purchased oil on the market really wanted the oil to sell.

That changed in 2000 when then-President Bill Clinton signed the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which created what has come to be known as the Enron loophole. The loophole, Babb said, changed the value of oil from a commodity to be sold to a cash cow to be manipulated.

“They are able to control the market to a degree and ensure themselves a profit,” Babb said. “Oil commodities now follow the stock market very closely.”

Oil prices historically have been tied to use, but no longer. For example, just a few years ago the average Maine homeowner consumed about 1,300 gallons of oil each year. The average is now about 800 gallons, thanks in part to the push to make homes more energy-efficient.

Such a drastic decrease in demand should have pushed prices down, but they have only increased.

“Sometimes the best cure for high oil prices are high oil prices,” Babb said. “People are forced to use less oil (and prices drop.) That’s how it normally happens, but speculators have changed the equation.”

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act signed into law in July 2010 is designed to rein in oil speculation, Babb said; but the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which is tasked with implementing the law, has been slow in developing rules.

“Almost every other commodity is tightly regulated,” Babb said. “It should be the same with oil commodities.”

Currency production

Babb attributes the depth and duration of the economic recession to soaring oil costs.

The government’s response to the recession has only worsened the problem, he said. As the Federal Reserve has printed money to bail out lending institutions, the value of the U.S. dollar has plummeted. All oil is traded in U.S. dollars.

“When we’re printing more money, it puts more in the market, making the dollar worth less,” Babb said. “As the dollar becomes worth less, oil becomes worth more.”

Volatility, particularly, is a reflection of the dollar.

“When the dollar goes down, the cost of oil goes up,” he said.

Energy policies

The U.S. imports about 60 percent of its oil from Canada and Mexico. Fractions come from other nations, such as Venezuela; and a small fraction comes from the Middle East, Babb said.

“The U.S. is the biggest user,” he said. “It influences the prices when we don’t allow our own product to be brought out of the ground. If we would tap a fraction of the oil in this country, our economy would come roaring back.”

Domestic drilling has been opposed by environmentalists who fear damage to local ecosystems and who instead want to push for alternative energy sources.

Babb believes we can go after our own oil supplies while protecting the environment.

“It can be done responsibly. It should be done responsibly, but it needs to be done,” he said. “We have to address all these issues. Energy drives everything, but it’s not being addressed.”

Craig Crosby — 621-5642

ccrosby@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.