Claire Moulton is one of a handful of parents in Maine who is waiting for a missing child to come home.

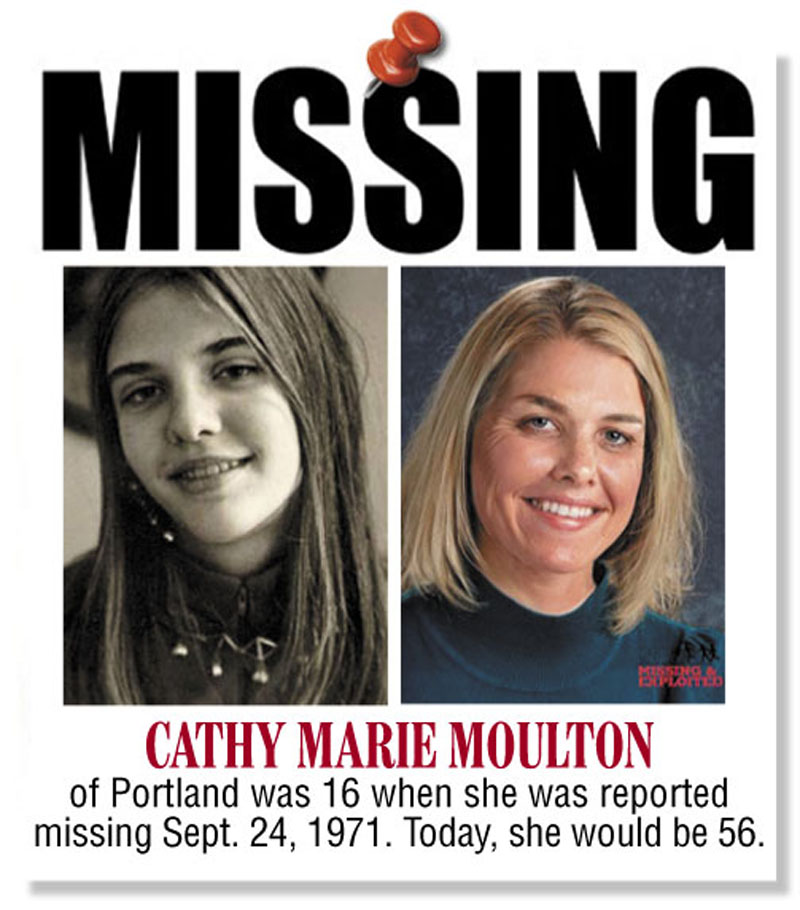

Moulton’s daughter, Cathy Marie Mouton was 16 years old when she was last seen on Sept. 24, 1971. Today, she would be 56. Every day, for more than 40 years, Moulton’s mother is preoccupied with thoughts of her missing child.

“You never forget,” she said. “I mean, every day I pray that somehow, somewhere, we’ll find her.”

There are six unsolved missing children cases in Maine, according to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, a nonprofit organization, and state police. Four of the children disappeared in the 1970s, one disappeared in the mid-1980s and 22-month-old Ayla Reynolds of Waterville disappeared seven weeks ago.

Parents of three of the missing children describe an unending ordeal that haunts their thoughts every day. Without closure, it’s difficult to live a normal life, they said.

“It’s a nightmare,” Moulton said. “We’ve been living with this for a long time now.”

Cathy is the oldest of the Moultons’ three daughters. She was last seen walking on Forest Avenue in Portland, according to the Charley Project, an online database for missing person cases.

In the early days after her daughter’s disappearance, Moulton developed a ritual. “Our house had a sun parlor on the front, and every day I used to go out on parlor and look up and down the street expecting her to show up,” Moulton recalled. “I just couldn’t believe she wouldn’t be coming home.”

The ritual persisted for decades, she said.

“I kept doing it right up until a year ago when we moved. But, I had not-as-high hopes in recent years,” she said.

Moulton and her husband still live in Portland. They are in their 80s.

“At this point, we’re concerned whether we’ll ever know what happened to her before we die,” she said.

Hope for closure

Devorah Goldburg, public relations senior manager at the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, said the parents of missing children struggle with the uncertainty.

“It is very difficult,” she said. “Parents tell us repeatedly that the worst thing is not knowing.”

Goldburg said the center never gives up hope of finding missing children.

“No case is closed until we either find the child or learn with certainty what happened to the child,” she said. “We work very hard to keep hope alive, and to remind communities that the child is still missing.”

Carol Ross said her hope wavers.

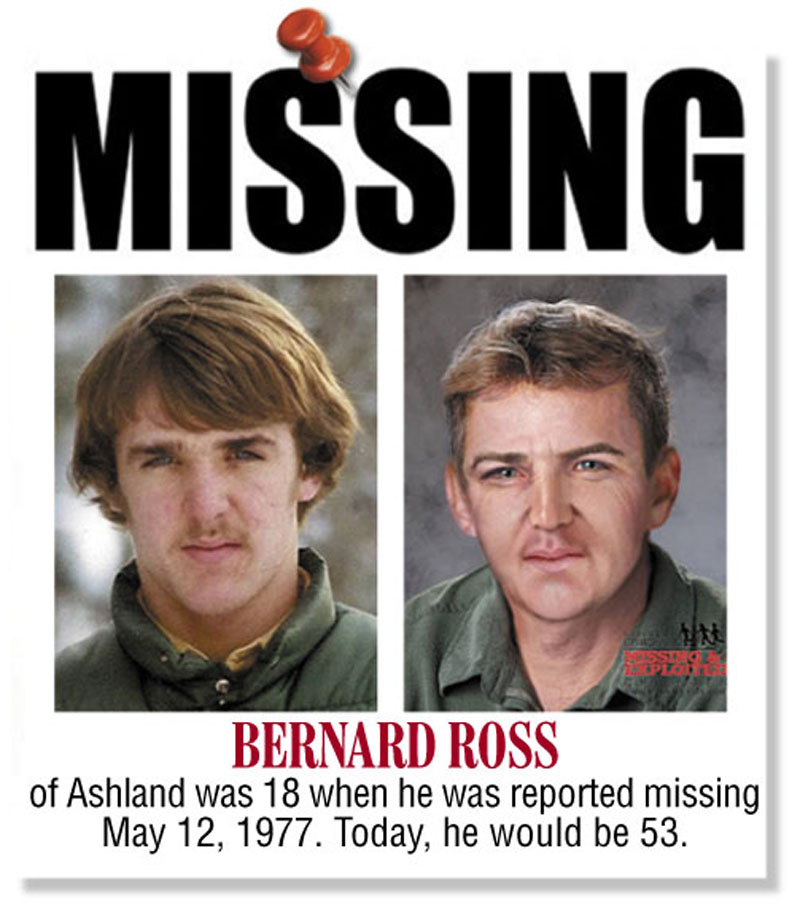

In 1977, her son, Bernard Ross Jr., was 18 when he drove off in his aunt’s pickup truck in Presque Isle. Ross was reportedly despondent when he left. The truck was later found, but Ross is still missing.

Today, he would be 53.

“I go from thinking he’s out there somewhere — maybe in a hospital or carrying on a new life,” Carol Ross, 74, said. “Other times, I think he must be gone, because he would have called us.”

Ross and her husband, Bernard Ross Sr., 76, live in Portland.

Recently, the Rosses got a glimpse of what their son might look like today after the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children developed an age-progressed image. The center combined the parents’ and siblings’ facial features with their son’s high school senior portrait to show what a middle-aged version of Bernard Ross Jr. might look like.

“It’s still kind of strange to look at it,” the father said.

He added that news of missing children, like Ayla Reynolds, stirs old feelings.

“It brings up some pain, some grief and hope for that child,” he said.

When a missing child is a toddler

In addition to Ayla Reynolds, there are two unsolved missing children cases in Maine that involved small children. Two young boys vanished in the early 1970s in separate incidents.

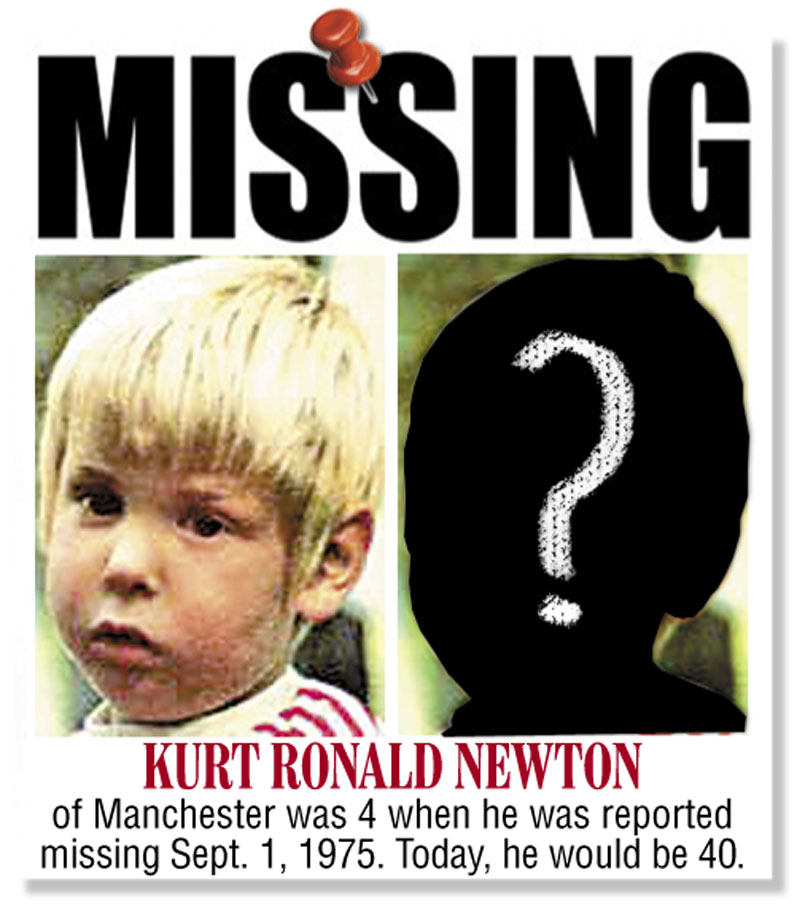

On Sept. 1, 1975, Kurt Ronald Newton of Manchester vanished from Natanis Point Campground in Chain of Ponds in western Maine near the Quebec border. He was 4 at the time. Today, he would be 40.

Kurt was last seen riding a Big Wheel tricycle near his parents’ campsite, according to the Charley Project.

Department of Public Safety Spokesman Steve McCausland said efforts to find Kurt were historic.

“One of the largest searches of the decade was mounted up there to try to find him,” he said. “All they found was his tricycle.”

After the search concluded, Kurt’s parents mailed missing child posters with Kurt’s photo to every school district in the United States.

His parents, Ronald and Jill Newton, who still live in Manchester, declined a reporter’s request to be interviewed.

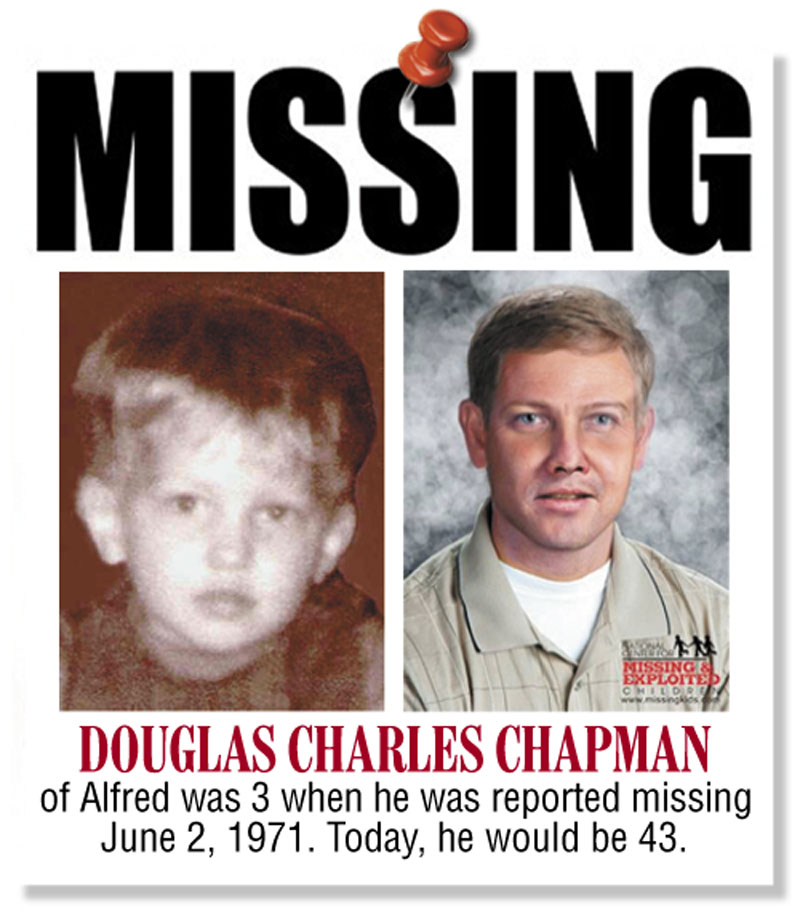

Four years before Kurt Newton disappeared, Douglas Charles Chapman was last seen playing in a sand pile outside his parents home in Alfred on June 2, 1971.

He was 3 at the time. Today, he would be 43.

A search dog followed Douglas’ scent from the home, “through a field, past an apple orchard onto a farm, and down the driveway to the main road,” according to the Charley Project.

The ensuing six-day search was one of the largest ever for a missing person in York County, according a 1993 Associated Press story. It included about 3,000 volunteers, aircraft from the Navy and National Guard, and scuba divers.

Officials even pumped local wells dry to look for the boy, the story reported.

In 1993, the boy’s father, Gary Chapman, successfully pleaded with police to deepen the investigation.

He said police had been convinced Douglas had wandered off, died and would eventually be found, but Chapman wanted investigators to consider abduction.

The boy’s parents are divorced. His mother, Carole Allen, moved to New York, and his father to Waterboro. Neither could be reached for comment.

Someone has answers, Allen said in 1993.

“It doesn’t make sense that a child should disappear and nobody saw anything,” she said.

In 2001, Chapman told the Hartford Courant that his son’s disappearance was difficult for the community to accept.

“People want to believe that these things don’t happen and kids just don’t disappear,” he said. “Well, kids disappear way too often.”

McCausland said police still get tips on both missing boys.

“We, from time to time, have received inquiries from people who either think they themselves could be Douglas or Kurt, or thought they recognized one of them,” he said. “None of those leads have panned out.”

Never give up

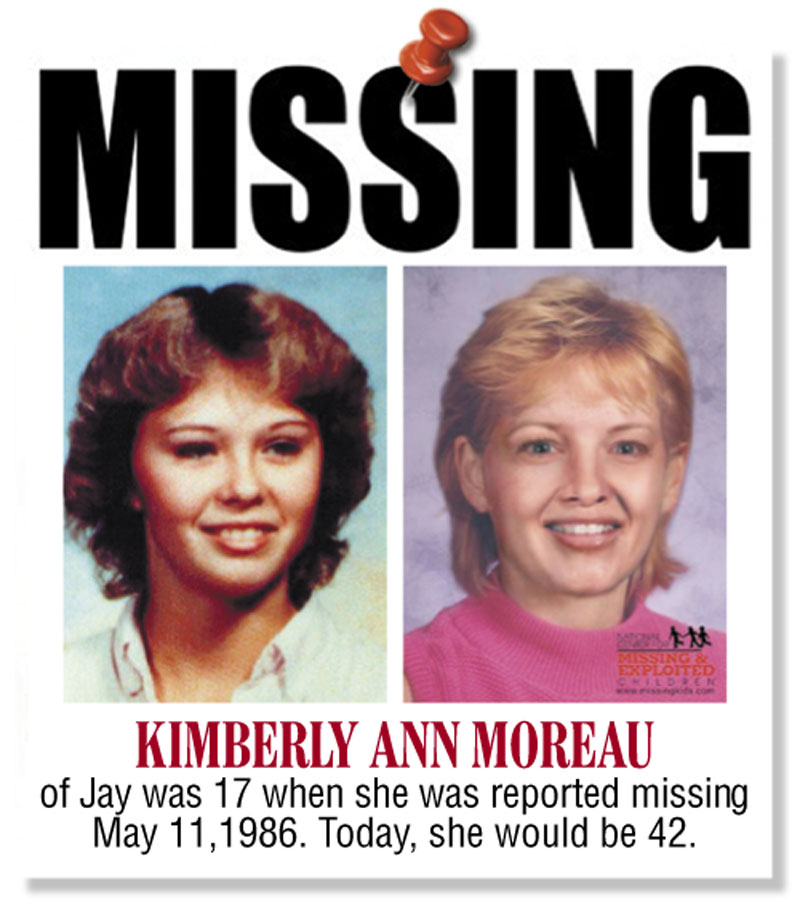

Richard Moreau’s daughter vanished nearly 26 years ago. Every day, he wonders what happened to her.

Kimberly Ann Moreau was last seen in May 1986 in Jay when she climbed into a white Pontiac Trans Am driven by a man she had met earlier that day, according to the Charley Project. She was 17 at the time. Today, she would be 43.

The driver of the car is considered a person of interest in the case, but he was never charged.

Richard Moreau, 69, said he and his wife knew right away that something was wrong when their daughter wasn’t at home at dinnertime. The next morning, the Moreaus reported their daughter missing, but police didn’t get involved for another 48 hours, he said. When they did, police said the girl had probably run away.

Moreau and his wife didn’t agree with police, so they performed their own investigation with the help of two family members. The Moreaus talked to people in the area, took statements and compiled a folder of evidence that they eventually turned over to detectives.

“We could not rely on anyone else to get it done,” he said.

Four months later, state police took over the investigation, Moreau said.

“They realized this was something more than just a child that ran away, and they listed her as exploited and endangered, which, as far as I know, is how she remains listed today,” he said.

Those initial years were difficult, Moreau said.

Soon after Kimberly disappeared, Moreau and his wife concluded that their daughter was dead. Within a year, Kimberly’s grandfather died from heartbreak, Moreau contends. A year later, Kimberly’s mom died of cancer.

“I had three years of what I classify as total hell,” Moreau said. “Pardon my language, but that’s the best way I know how to put it.”

A few years later, in 1991, Moreau took matters into his own hands again after he was encouraged by private investigators to spread awareness of his daughter’s disappearance.

Moreau began taping missing child posters onto utility poles throughout the area, he said. Also, as a supervisor in the shipping department of International Paper Co., Moreau would insert missing posters into shipments. Those posters have been sent to cities in Asia, Europe and South America.

“She’s basically been around the world,” he said of his daughter’s image.

Moreau estimates he has distributed more than 50,000 posters, and that number continues to climb.

As recently as last month, Moreau was hanging new posters in Jay, he said. Whenever posters deteriorate from weather, Moreau replaces them with fresh copies.

Moreau said he hopes his daughter’s remains will be found so she can be buried in the local cemetery next to her mother, grandmother and grandfather. He wants the opportunity to visit his daughter’s grave and talk to her. And he’s imagined countless times what it would be like to have that kind of closure.

“It would be like taking 10 tons off my shoulders,” he said. “I’d be able to go to bed at night, lay down and get a full night’s sleep without ever waking up.

“I would be able to say, ‘Darling, I know you’re home, and I love you.’ “

Ben McCanna — 861-9239

bmccanna@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.