ALEXANDRIA, Va. — A fisheries commission postponed a decision Wednesday on whether to impose quotas or other restrictions on commercial fishing for baby eels, the translucent fingerlings that have become big business in Maine with prices that have topped $2,000 a pound.

The delay means that any new regulations on elvers or “glass eels” may not be finalized until early next year just prior to the 2014 elver season, if then. But several people who fish for elvers in Maine were pleased to emerge from Wednesday’s meeting without severe catch limits on a species that now ranks as the second most-valuable fishery in Maine after lobster.

“It’s better than closure” of the fishery, said Darrell Young, founder of the Maine Elver Fisherman Association.

For the second straight meeting, members of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s American eel management board were unable to reach any consensus on whether to establish quotas for elvers and, if so, how to carry them out.

Instead, commission members opted to direct a special policy committee to craft a proposal for a quota system applicable to the entire East Coast — opening the door to fishing beyond Maine and South Carolina, the only two states with commercial elver fisheries. The latest proposal is expected to come back to the commission in October, with final approval potentially by February.

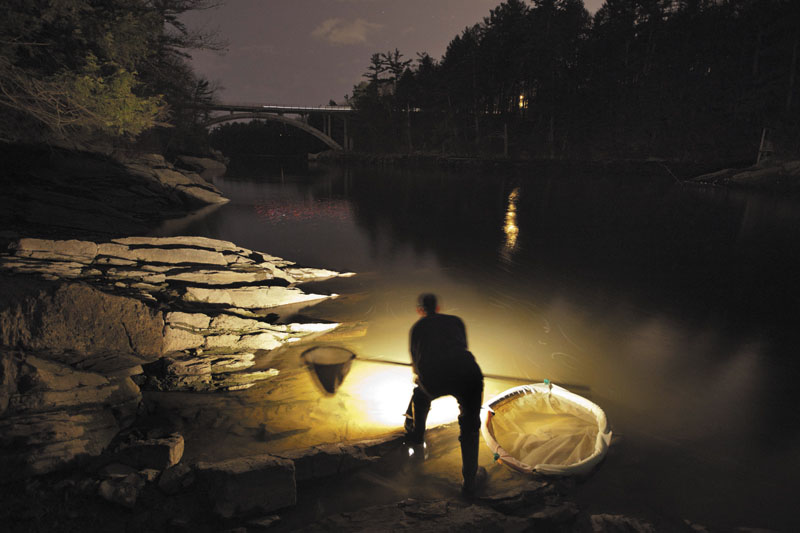

Maine issued 744 elver licenses this year, resulting in a catch exceeding 18,000 pounds. Beginning in mid-March, licensed fishermen staked out coastal streams to catch glass eels in long, conical nets or hand-dipped nets as the eels swam up river.

Terry Stockwell, director of external affairs at the Maine Department of Marine Resources, chaired the working group that proposed a list of recommendations that were only partly adopted on Wednesday. Nonetheless, Stockwell said he was comfortable with the decision to delay action on elvers, saying he believes it will lead to stronger and fairer regulations.

But Corey Hinton, a Washington-based attorney representing Maine’s Passamaquoddy Tribe, said the tribe hopes any changes are in place prior to the 2014 fishing season to avoid leaving all parties in “regulatory limbo.”

Unlike the state of Maine, the Passamaquoddy Tribe sets quotas for its fishermen as a way to protect the resource. But the tribe was involved in a high-profile sovereignty dispute with the Maine DMR this year after tribal leaders issued several hundred more elver permits than allowed by the state.

“We are encouraged by the direction the commission appears to be going,” Hinton, a Maine native and Passamaquoddy tribal member, said of the proposed quota-based system. “But the pace with which they are moving is definitely troubling. We had hoped they would make a decision at the last meeting.”

It was clear from Wednesday’s discussion that disagreements remain on a number of fronts, despite months of work by the working group and hours of discussion among commission members.

One of the biggest areas of discord is on the overall health of the American eel population. The stocks have been labeled as “depleted” and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is currently studying whether eels need protection under the Endangered Species Act.

But fishermen and some state regulators insist that they are seeing huge numbers of glass eels making their way up the rivers where they will spend most of their lives.

At one point during Wednesday’s meeting, a commission member proposed directing the policy committee to language for a 5,300-pound quota to be equally divided among the 15 states within the commission’s jurisdiction. Maine fishermen harvested more than 18,000 pounds of elvers this past spring. Under the 5,300-pound quota, Maine’s share would drop to just 353 pounds.

The proposal was rejected after commission members said it was overly restrictive.

“To give an equal allocation at this point certainly would be a disservice to the state of Maine,” said Tom McElroy, a representative from Rhode Island. “I don’t believe they have done anything wrong to have (allowed) fishing that was legal and properly managed.”

Jeffrey Pierce, executive director of the Maine Elver Fisherman Association, said his members could probably live with a quota of around 17,000 pounds but not one that reduces the catch by 45 percent, as others have suggested.

“I think the glass eel fishery was picked on pretty hard today. I don’t think we got a fair shake,” Pierce said afterward. But Pierce said he was pleased that the 5,300-pound quota proposal was rejected.

The American eel is, in many ways, an enigma despite the fact that it is one of the most widely dispersed species in the world. That lack of information complicates efforts to craft regulations, commission members said.

Eels are born from eggs spawned in the Sargasso Sea near the Bahamas. The tiny hatched eels are then carried by currents up the entire eastern seaboard, where they eventually find their way into rivers and streams.

Eels may spend 15 to 20 years in Maine’s freshwater rivers and streams before returning to the Sargasso Sea as adults to spawn. But habitat loss, hydropower turbines, pollution and other factors have dramatically reduced their numbers, scientists say.

Maine and South Carolina are the only two states that allow commercial fishing for elvers. But interest in other states has risen along with the price that Asian buyers — primarily for aquaculture operations — have paid for the baby eels.

“This is an opportunity unlike any other really that I am aware of,” said Louis Daniel, director of the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries. “When I look at the value of this fish in Maine, it is worth more than the two top fisheries in North Carolina.”

Kevin Miller can be contacted at 317-6256 or at:

kmiller@pressherald.com

Twitter: @KevinMillerDC

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story