Rosie the Riveter was not just one woman. She was Geraldine Doyle, who found work as a metal presser in the American Broach & Machine Co. of Ann Arbor, Mich. She was Rose Will Monroe, a Ford employee who built B-24 and B-29 bombers at the Willow Run Assembly Plant near Ypsilanti, Mich. She was Rosalind P. Walter, from Long Island, who worked as a riveter on the night shift on a Corsair fighter airplane and who inspired the 1942 hit song “Rosie the Riveter.”

The fact that “Rosie” wasn’t any one individual is true on two levels. Many women in World War II-era America embodied the “Rosie” icon, in that thousands upon thousands of women took up traditionally masculine, down-and-dirty jobs in the factories and shipyards.

Even the icon herself, however, was not a representation of a single character. “Rosie the Riveter,” as we know her now, is a fusion of cultural fragments, some real, some fictional.

J. Howard Miller painted classic image of the woman who looks with cat eyes at the viewer, flexing a rugged muscle and flaunting a sharp cheekbone, the poster girl (to put it quite literally) for the slogan “We Can Do It!”

Norman Rockwell was the creative mind behind another of these fragments, perhaps less well known than Miller’s, but one that deserves the same iconic status.

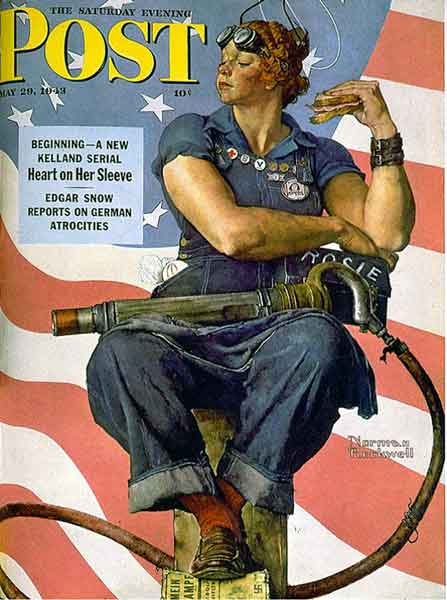

Rockwell’s Rosie, whose name we know from the lunchbox where her elbow rests indifferently, sits on a stump during her sandwich break, riveter in her lap, factory goggles pushed up on her forehead.

Rockwell used a woman by the name of Mary Doyle Keefe as his model for this Rosie, who appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1943.

It is presumed that the basic composition of the painting, that is, the naming of the woman Rosie and the riveter in her lap, is a reference to the popular song of the time “Rosie the Riveter,” the lyrics of which celebrate the female factory workers of the war effort.

Rosie’s muscular physique, dirty face and her worn overalls suggest that she is comfortable working in a factory, traditionally a man’s job, to support the United States war effort. She looks strong and confident, a far cry from a dainty “dame.”

The patriotic symbolism in the painting is abundant. In fact, it is hard to miss. Besides “Old Glory” waving in the background, Rosie sports several patriotic buttons and pins on her chest, including a “V” for victory.

Many scholars have noticed the image’s resemblance to Michelangelo’s “Prophet Isaiah,” as painted on the Sistine Chapel. So what was Rosie a prophet of? She does convey a sense of superiority in Rockwell’s painting. What or who is she superior to, and what higher power does she have the privilege to communicate with?

In the Bible, God tasked Isaiah with converting sinners to saints and trampling on evil, just as Rosie does to Hitler’s ideology. The resemblance to Isaiah, complete with a halo above her head, suggests that she is fighting for God’s cause — to defeat the original Axis of Evil — and to preserve the American Way. With the rivet gun, a symbol of America’s industrial dominance, in her lap and with her foot literally crushing a copy of Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf,” Rosie shows a uniquely American spirit, an unequaled strength and an indignation to Hitler and his Nazis for trying to crush the American Way.

She is 100 percent American patriot and she is not to be messed with.

It is not entirely absurd to consider the painting a token of feminism. If Rockwell’s Rosie is a prophet, it seems she must be communicating with the feminist movement in its current and future stages.

If this is so, this Rosie is a prescient figure representing the progress of gender equality that had yet to appear. It is as if she is not just confident about, but actually knows, what kind of progress women will make in her country.

After all, today’s women are accepted in the American workforce, although even at this point in history, many would say feminism has a long way to go. Some may even argue that there will always be progress to make in the feminist movement — that absolute gender equality will never exist, but that it is worth it to keep striving for.

This outlook makes Rockwell’s painting utterly timeless and an undying symbol for America that is important in a historical context as well as to generations of empowered women.

Essay by Amanda Buel, http://rosietheriveter wecandoit.com. Reprinted with permission.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.