E TOWNSHIP — Only 1,638 feet above sea level, Number Nine Mountain isn’t on any list of notable Maine peaks. Like adjacent Maple, Saddleback and Hedgehog mountains, Number Nine is a modest bump in the vast woodlands that stretch as far as the eye can see in this corner of central Aroostook County.

In autumn, the hills form a golden backdrop for tiny Number Nine Lake and the two dozen camps that ring its shores.

Over time, the 12-mile gravel road from Bridgewater to the lake has been widened for logging trucks. Electricity – which comes from nearby Canada because Aroostook County isn’t connected to the U.S. power grid – arrives on a single pole run.

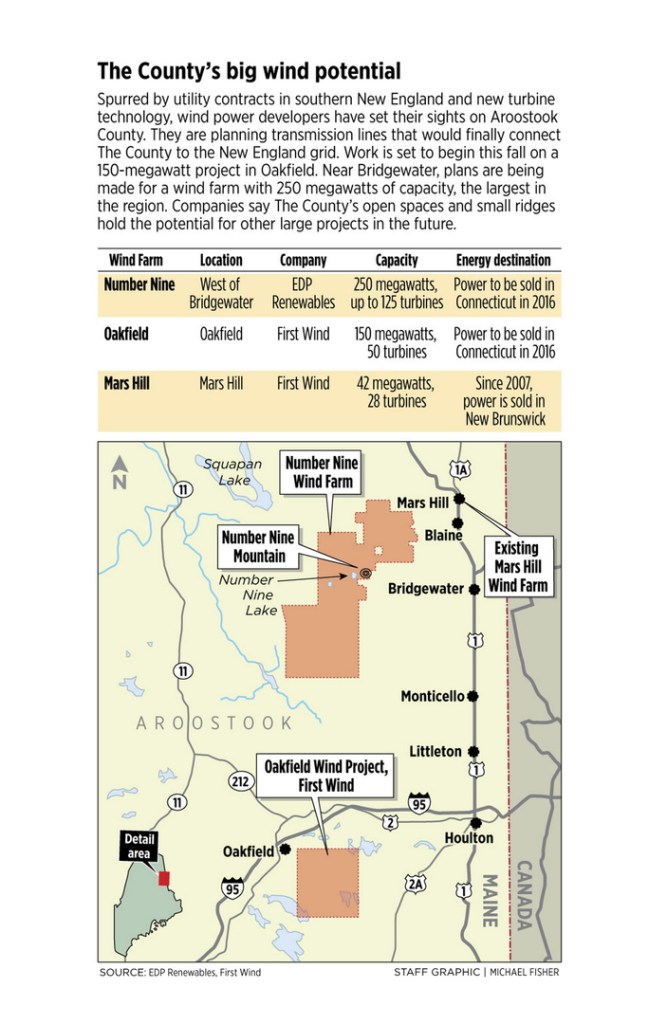

This seems an unlikely place to build New England’s largest wind energy project. But this is where EDP Renewables, part of a global energy company, plans to erect a $500 million wind farm to generate power for consumers in Connecticut. The project, featuring 125 towers with blade tips that could reach 400 feet in the air, would be scattered for miles across the hills and have a capacity of 250 megawatts of power – enough to run 74,000 homes for a year.

EDP Renewables is not alone here. Twenty-five miles to the south, on wooded hills that surround the pasture and cropland of Oakfield, Boston-based First Wind is poised to start construction on a $400 million wind farm. The 50 turbines there will have the capacity to generate 150 megawatts, and fulfill contract agreements with utilities in Massachusetts.

Both companies say they see the potential for hundreds of additional megawatts of capacity in Aroostook County, and are willing to spend tens of millions of dollars to hook into the New England grid. The two projects, as well as others that may come, have the potential to create a major hub for wind power in an area better known for its potatoes, long winters and access to Maine’s North Woods.

The trend is being driven by new state policies in southern New England, which are compelling utilities to sign long-term contracts for unprecedented amounts of renewable power. At the same time, modern turbine technology has lowered the per-hour cost of a kilowatt, making wind more competitive with other sources of energy, such as natural gas.

The combination of these factors has finally made it economical, developers say, to build the expensive transmission lines needed to send Aroostook’s wind to the U.S. market and, in the process, bring badly needed revenue to one of the poorest parts of Maine.

“Northern Maine is routinely referred to as the holy grail,” said Katie Chapman, EDP’s project manager for the Number Nine Wind Farm. “The limiting factor is transmission.”

Chapman’s company plans to build a 40-mile line that can handle 1,000 megawatts of energy, an oversized connection that hints at the desire for future projects. First Wind is planning a 59-mile line that could cost $80 million, a fifth of the total Oakfield project. These lines eventually could be operated by other companies, or help integrate wind into larger plans to move power from Canadian hydroelectric dams to southern New England.

Developers like Aroostook County for its remote setting, away from tourism centers and high-value mountains. The hills here may be small and spread around, but it turns out this topography is good for wind power production. The vast open spaces let breezes pick up speed across the landscape and arrive at the wind farm with less turbulence. That translates into “cleaner” wind. Today’s taller turbines and bigger blades can extract energy from this wind with efficiencies that were unheard of five years ago.

A preview of what this area has to offer came in 2007, when First Wind erected the state’s initial, large-scale wind farm at Mars Hill, northeast of here. The hill is unusual, a long 1,660-foot-high ridge on the Canadian border that rises out of the potato fields.

First Wind had no choice at the time but to sell the power from Mars Hill in neighboring New Brunswick. Now it has a New England option, supported by long-term contracts.

OBSTACLES AND OPPOSITION

As with all major construction ventures, Aroostook’s wind potential faces obstacles.

Any new transmission line must be approved by ISO-New England, the regional grid operator. Engineers must determine that hooking up large amounts of far-flung wind power won’t jeopardize the stability of the grid. That’s a growing concern. Northern Maine is the weakest part of the regional grid, the ISO says. Developers who don’t install robust connections run the risk of having their project’s output taken off-line at times, something the ISO already has done.

Competitors also may slow things down. Two energy companies that lost out to EDP in Connecticut’s renewables bidding recently raised questions about the process. Connecticut regulators approved the contract last week.

Anti-wind activists are, of course, dismayed and have vowed to fight environmental permits.

Last week, Friends of Maine’s Mountains testified at a hearing before the Massachusetts Public Utilities Commission, which must approve utility contracts for the wind farm in Oakfield as well as five other proposed projects in Maine. The group’s public affairs director, Chris O’Neil, argued that regulators should consider the damage that will be done to his state.

“The woefully low energy density of grid scale wind development, relative to its sprawling scope and scale, has the potential to destroy Maine’s quality of place for very little benefit – economic or environmental,” O’Neil said.

Utilities have said that the long-range contracts they signed for Maine wind power are in the range of 8 cents per kilowatt hour. They say that’s comparable to the cost of electricity from natural gas, which generates more than half the power in the region.

In his testimony, O’Neil cited ISO-New England figures that wholesale electricity costs last year fell to a 10-year low, to 3.6 cents/kwh. He didn’t mention that wholesale natural gas prices were at extreme lows last year and now are rising.

While price is a talking point, opponents object most strongly to the visual impact that hundreds of wind towers will have on Maine’s scenic, rural vistas. They note that wind has a limited operating capacity in the Northeast, spinning turbines only around 30 percent of the time, over the course of a year. Overall, wind doesn’t generate enough power to greatly reduce the use of fossil fuels, they say, so isn’t worth the impact on the environment.

“Most people never get up to Aroostook,” said Penny Gray, a wind power opponent who is a co-owner of the Harraseeket Inn in Freeport. “It’s the other Maine. It’s big-sky country and the big woods.”

But Gray, who owns an off-the-grid home in Fort Kent, acknowledged that The County doesn’t have the same tourism and scenic attractions as Maine’s western mountains, which have been a base of anti-wind sentiment.

“I don’t know,” she said. “There’s almost a sense of despair (in Aroostook). No matter what residents say, they’re going to have to live with these things.”

That’s been the outcome, so far. Lakefront owners in Island Falls, one town away from Oakfield, lost a 2011 Maine Supreme Judicial Court challenge to an earlier version of First Wind’s project. Conversely, Oakfield voters overwhelming approved the wind farm, eager for the millions of dollars in financial benefits that will flow to the town for 20 years.

‘WHOOSH, WHOOSH, WHOOSH’

Like much of rural Maine, Aroostook County suffers from an aging, shrinking population. The official jobless rate hovers around 9 percent, nearly twice that of Greater Portland. The largest employers include community hospitals in Presque Isle, Fort Kent, Caribou and Houlton, along with a paper mill in Madawaska, a potato processor in Easton and a couple of Walmart stores.

People here remember when a Texas company called Horizon Wind came calling five years ago with the promise of jobs and investment. Big plans were drawn up, but nothing happened. Horizon went bust during the recession, and was bought eventually by EDP.

News that EDP had revived the old Horizon project was just getting around earlier this month. October is a busy time here and The County is preoccupied, moving to the rhythms of autumn.

Trucks loaded with potatoes labor up U.S. Route 1, as farmers finish the harvest. Pickups pull trailers draped with dead moose out of the woods, as hunters return from their annual ritual. Chairlifts start and stop at Big-rock Mountain in Mars Hill as workers prep the ski area for the first flakes.

Fall also is a time to close up camp.

Diane Libby eased her four-wheel-drive truck up the narrow track leading to Number Nine Mountain, topped with a fire tower/communications array. At the summit, she could feel the bracing wind. She could spot the outline of Mount Katahdin on a cloudy horizon. She could look down on Number Nine Lake, where a couple of dozen camps ring the shoreline.

Libby’s family has come here to hunt, fish and relax in solitude for half a century. Her dad, Emmett Porter, heads the local camp owners association.

A retired chemical engineer who returned home after a career in New York, Libby said she’s not against wind power. She simply wonders how EDP can put up all the towers, roads and wires without washing fish-killing silt into the streams, and subjecting camp owners to noise and the sight of massive turbines.

“I come out here for the peace and quiet,” Libby said. “I don’t come out here for whoosh, whoosh, whoosh.”

Emmett Porter’s log-sided camp is a living history display of a way of life. Rows of deer antlers hang on one wall, the hunt dates inscribed below. Smiling children hold up fish in photos. The trophy moose head that Porter shot near the camp last year peers over the scene.

Down the lake a bit, Rodney Jones had been out hunting partridge and was checking on his wife’s family’s camp. He hadn’t heard the news that the wind project was back on, and wasn’t happy about the prospect.

From the camp dock, Jones could see Saddleback Mountain on his left. Number Nine Mountain rose on his right. He and Libby chatted and wondered: Can EDP build its wind farm without erecting turbines that can be seen and heard from the camps?

“Nobody wants to see windmills along the lake,” he said.

JOBS AND COMMUNITY BENEFITS

It’s too soon to say whether that wish can be granted. EDP is still working on specifics of the project, Chapman said. The company has just begun meeting with local officials to introduce the plans. It soon will open a field office in Presque Isle. The permitting process is ramping up, with a goal of being in operation in 2016.

Most of the Number Nine Wind Farm will be in the Unorganized Territory. The closest town is Bridgewater, on the Canadian border south of Mars Hill. For travelers on Route 1, Bridgewater is little more than a wide spot in the road. But Bootfoot Road, the only pavement heading west, will be a prime entry point to the project site.

Bridgewater’s town manager, Jill Rusty, said there’s not much awareness yet among the 600 residents. She met briefly with Chapman and expects the company to contact selectmen soon.

Keith Kingsbury, a selectman and potato farmer, said he hopes the project will bring some financial benefits to town. Maybe EDP will upgrade some roads, or lease a building. Kingsbury also has a camp on Number Nine Lake. He recognizes some opposition there, but expects widespread support in town.

“If there’s going to be a little financial boost and it’s not in your backyard, why not?” he said.

EDP has said the project will create 300 construction jobs and a dozen permanent positions. It also has leased 58,000 acres for turbine sites and roads and transmission easements.

Wind power developers in Maine also have to fund an annual community benefits package, a payout based on turbine generating capacity. It’s too early to know how that package will come together for Number Nine, but the company has pledged to work closely with local residents during the development process.

“We expect to do a lot of listening over the coming months to make sure that our project benefits communities and brings much-needed, clean, renewable energy to New England,” Chapman said.

‘STABILIZING’ FACTOR IN OAKFIELD

That process already has played out in Oakfield, where the dynamics are very different.

First Wind’s project is largely within town limits. That gave Oakfield an opportunity to be a vigorous participant and negotiator in the process. The result was a community benefits package that will pump a total of $25 million into the town over 20 years. Money will go to road construction, a new public safety building and new firetrucks, among other things. Another part of the package will provide tax relief to 230 families. This is on top of 300 or so construction jobs.

The money is a big deal in a town of 700, where there hasn’t been enough tax revenue to pave town roads for years. Oakfield prospered when the Bangor & Aroostook Railroad hauled potatoes and lumber out of The County. Now the boom times exist only in old photos at the Oakfield Railroad Museum, in the former train station. The largest private employer is Katahdin Forest Products, a family business known for its innovative cedar log cabins.

“This is stabilizing the town,” said Dale Morris, the town manager. “Done the right way, it’s setting Oakfield up for quite some time.”

To illustrate the need, Morris and Jim Sholler, a former selectman who chaired the town’s wind farm review committee, showed off the condition of the town’s 60-year-old fire barn. Firetrucks just barely fit inside. Upstairs, Morris jumped on the floor. The springy rebound suggested the floor’s days of holding a crew of first responders are numbered.

Morris and Sholler are proud of the town’s deal with First Wind. But Oakfield also benefited from the passage of time, and the experience at Mars Hill. Some of the 28 turbines there are close enough to homes to bother residents. Some homeowners have reported sleep problems and other health issues. Oakfield wanted to minimize similar controversy.

The town created a local wind farm review committee, hired a sound consultant and negotiated an operations ordinance. State law requires a setback from wind turbines designed to keep noise below a certain level. Where that level would be exceeded, First Wind negotiated sound easements with roughly 20 people. They will be paid an undisclosed sum each year for 20 years, in exchange for living closer to the towers. In some instances, First Wind couldn’t reach a deal with landowners, and had to move turbines to a different location.

PUBLIC MEETINGS AND ACCEPTANCE

One of the sound easements was negotiated with Greg McNally. A Registered Maine Guide and a fur tanner, McNally lives on 20 acres of former pasture in a Katahdin log home. Sam Drew Mountain stretches beyond his patio door. It’s one of the Oakfield Hills, the rolling ridges that punctuate the town’s farm fields and woodlands.

McNally’s home is 2,000 feet from a turbine site, but he thinks the tree line will block the view. He has taken a few trips down to First Wind’s Stetson Wind Farm, in Washington County near Danforth, and decided he can live with the sound. In his opinion, the wind farm is a business that won’t require town services and will provide money to improve the roads.

“I didn’t have a problem with them going up in the first place,” he said. “I’d rather have these than a super Walmart or a nuke plant.”

McNally’s acceptance is typical of the reception wind power has gotten in Oakfield, according to Matt Kearn, First Wind’s vice president for business development. The lessons First Wind learned at Mars Hill have led it to increase turbine setbacks and seek more community input, he said. The Oakfield project was reviewed at 10 public meetings. The community benefits package was approved by a vote of 100-1. The tax agreement won 80-20.

Oakfield is scheduled to be on line in 2015. As work begins here, First Wind also has nine towers erected west of town that are collecting wind and weather data.

“We’re interested in doing more, long-term,” Kearn said.

Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story