WATERVILLE — Two years and 20 searches after she disappeared, Ayla Reynolds is still missing.

Police say someone knows what happened to the child, but no one is telling. Officials say as time goes by, finding out the truth gets harder.

The blond-haired, blue-eyed toddler who would now be 3 and a half years old was last seen in December 2011 at her 29 Violette Ave. home. Her father, Justin DiPietro, reported her missing the morning of Dec. 17, telling police he last saw her when he put her to bed the night before. DiPietro said he awoke to find Ayla’s bed empty, and he believes someone took her from the house.

State police believe Ayla is dead and have said that the three adults who were at the Violette Avenue home when Ayla was reported missing aren’t telling authorities everything they know.

In the last two years, police, state game wardens and volunteers have searched for Ayla, relatives and supporters have set up websites and written blogs, and psychics have offered opinions. Authorities say Ayla’s case has become the largest police investigation in state history.

Ayla is one of nearly 25,000 children in the U.S. reported missing who have been gone more than 60 days, according to Bob Lowery, senior executive director of the missing children’s division of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. An average of about 2,000 children are reported missing in the U.S. every day, he said.

Many are found quickly and returned to their homes within a day or so, he said.

“Cases like Ayla’s are unusual,” Lowery said last week. “A child of this age, missing this long, is rare, but we do experience them. We do see them around the country.”

Maine State Police continue to work on the Ayla case nearly every day, according to Steve McCausland, spokesman for the state Department of Public Safety. Police are interviewing and re-interviewing people, reviewing records and analyzing evidence as part of the investigation, which has cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, he said.

Lowery says the search must continue.

“We don’t give up hope for children, but we also don’t give false hope,” he said.

Even though nearly two years have passed since Ayla’s disappearance, investigators are still determined to find her, McCausland said.

“There are some days when there is frustration that creeps in and then we remember who we are working for and that frustration subsides because we’re working for Ayla,” he said. “The determination of investigators is as strong as it was two years ago and I’ve seen that firsthand and it is a determined, committed group of investigators that have been working this case and that work continues.”

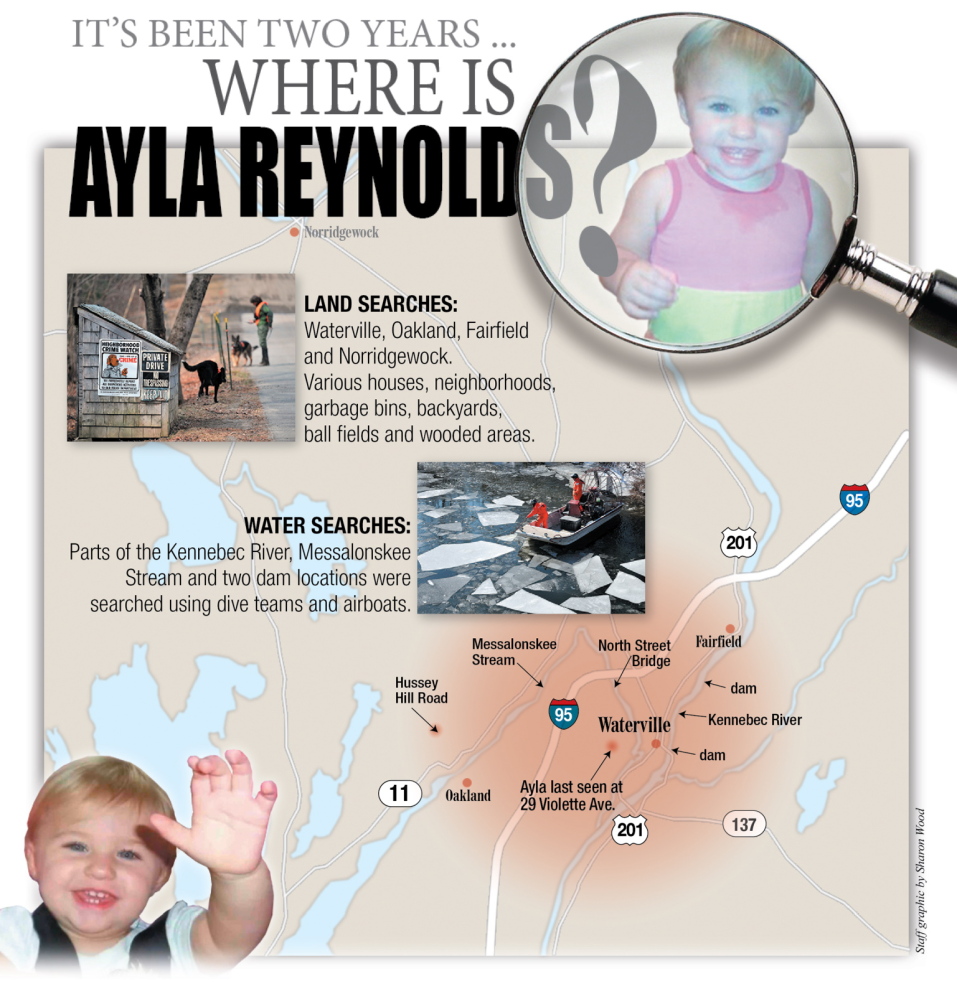

Searching for Ayla

McCausland said this week that 20 searches have been conducted for Ayla in the two years since she was reported missing. Some of those organized searches have been public and some kept private, he said.

The Maine Warden Service coordinated the searches, which have included state and local police, FBI agents, firefighters, volunteers and dogs.

They have searched by air, land and water, inspected neighborhoods, gone house-to-house and scoured riverbanks, woods and fields.

Dive teams have searched the Kennebec River, Messalonskee Stream and other bodies of water in central Maine.

The most recent large-scale search was off Hussey Hill Road in Oakland, where police spent a morning diving in a pond in a field and searching a wooded area, with no sign of Ayla.

“The searches will continue,” McCausland said this week. “There will be more searches. None at this point are planned, but there will be more.”

McCausland won’t discuss what, if anything, investigators have found during the searches, but he said the operations have allowed police to eliminate certain areas as possible locations for evidence of Ayla’s whereabouts.

“There have been some items found which we have disclosed following searches, but we have not gotten into any specifics,” McCausland said.

The latest search in Oakland yielded the discovery of bones, which police said were later tested and confirmed to be from an animal.

Although odds of finding Ayla alive are not good under the circumstances, Lowery, of the Missing and Exploited Children’s Center, said his organization will continue working to find her. The center sends representatives to the location where the child was reported missing, distributes images of missing children, develops age-progressed photos of missing children and help spread awareness.

Others found alive

Searches are important, as police look for the children as well as clues to their whereabouts, Lowery said. But he concedes that in many cases it’s like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

Time is the enemy, but there are exceptions.

“We have seen cases where children were found alive who were thought to be deceased,” Lowery said.

Examples include Jaycee Dugard, the 11-year-old girl kidnapped in 1991 in South Lake Tahoe, Calif. She was found in August 2009, after spending 18 years as the captive of her kidnapper, Phillip Craig Garrido.

Shawn Hornbeck was kidnapped Oct. 6, 2002, as he rode his bicycle near his home in Richwoods, Mo., and was missing more than four years before he was found Jan. 12, 2007. He had been kidnapped by Michael J. Devlin.

Elizabeth Smart was 14 when she was abducted from her bedroom June 5, 2002, in Salt Lake City and nine months later was found about 18 miles from her home with kidnappers Brian David Mitchell and Wanda Barzie.

And more recently, on May 6 this year, three women from Cleveland were rescued from a house where they were held captive by Ariel Castro, who abducted them between 2002 and 2004.

Smart and Dugard were both discovered because of alert strangers. Hornbeck and the women in Cleveland managed to escape their captors and get help.

The Ayla case initially was handled by Waterville police, which later turned the investigation over to state police. Waterville police still assist in the case, with officers from Waterville and other area agencies often seen participating in searches.

Waterville Police Chief Joseph Massey said he’s reluctant to comment on the case now because said his department is no longer the lead agency. But Massey said he thinks investigators do not want to miss an opportunity to crack the case.

“I think that’s a prudent thing to do,” Massey said. “I think a lot of people don’t realize that sometimes during an investigation we want to eliminate possibilities. When people talk about progress, that’s part of the process, eliminating people and eliminating areas. That certainly helps define the investigation.”

Massey conceded that generally the longer a case goes unsolved, the more likely evidence can be destroyed, lost or tampered with.

“So, in the best case scenario, we’d like to solve all serious cases within a few hours,” he said.

As time passes, police are also concerned about evidence being left out in the elements.

“Any time a person is reported missing, we’re dealing with a person, so time becomes very critical, particularly if the person is at risk or vulnerable because of their age, physical or mental condition,” Massey said. “When we get those types of cases, we aggressively work them and obviously, we know time can be a factor, so we put a lot of resources into those kind of investigations.”

The missing children’s center’s website lists the names of between 1,500 and 2,000 missing children, but the organization is working on between 3,500 and 4,000 cases, according to Lowery.

Someone out there has a key piece of information that is important to the case, even though that person may think it trivial, Lowery said.

“Ayla’s mother needs answers and we really urge that person to come forward and share that information,” he said.

The full story?

Three adults and three young children were in the Violette Avenue house the night Ayla reportedly disappeared. Besides DiPietro and Ayla, DiPietro’s then-girlfriend, Courtney Roberts, of Portland, and her young son were there, as well as DiPietro’s sister, Elisha DiPietro, and her infant daughter.

Justin DiPietro told police that when he put Ayla to bed Friday night, Dec. 16, 2011, she was wearing a green one-piece pajama outfit with polka dots and “Daddy’s Princess” on the front. Her left arm was broken and in a soft splint and sling. DiPietro said he fell on Ayla weeks before when he slipped while carrying groceries into the house.

The child had been in her father’s care since October while her mother, Trista Reynolds, was in a drug rehabilitation program.

On Dec. 15, 2011 — the day before Ayla disappeared — Reynolds, who lived in Portland, filed for full custody of her daughter.

Six days after her disappearance, police put crime scene tape around the house at 29 Violette Ave., which is owned by DiPietro’s mother, Phoebe DiPietro. Phoebe DiPietro reportedly was not home the night Ayla disappeared.

Two weeks later, police announced they suspected foul play. More than five months into the investigation, police said they believed Ayla was dead.

Focus turned to 29 Violette Ave., where she was last seen alive.

“We do not think we’ve gotten the full story from the three adults who were in the home that night,” McCausland said this week. “That would be Justin, Elisha and Courtney. Our stance has not changed. We think that they know more than they’ve told us.”

All three adults were contacted through Facebook this week and only one responded.

“All I have to say,” Elisha DiPietro wrote, “is that I love my niece and hope that she comes home soon.”

Seeking answers

Reynolds will not be speaking publicly about her daughter’s case this Christmas, according to her stepfather, Jeff Hanson.

Hanson, who manages the website www.aylareynolds.com, also declined to answer questions about the case, but emailed a statement to dozens of reporters, legislators and others, describing the pain the family feels two years later by her absence, particularly around Christmas.

The statement, which Hanson describes as an open letter, asks that people press for justice in the case.

“Demand answers from the state,” the statement reads. “Why are those present in the house where Ayla’s blood was shed decorating their trees and hanging their stockings while Ayla is out in the cold unknown for another Christmas? Why are they free to sing the songs of the season with their own toddlers when Ayla will never know ‘Silent Night,’ ‘Deck the Halls’ or ‘Joy to the World?’”

Authorities have said they found traces of Ayla’s blood in the house. Reynolds, citing evidence briefings shown to her by police, has described large amounts of Ayla’s blood being found in multiple locations.

The letter also targets the DiPietro and Roberts families, asking, “Where is the justice in the DiPietro and Roberts families building snowmen together or their children climbing on Santa’s lap for the iconic childhood photograph denied Ayla and those who loved her?”

It asks that those responsible be held accountable.

“We cannot truly know the peace of Christmas while our Ayla is out there somewhere, alone, and her killer and accomplices are smirking in their confidence the law won’t catch up with them.”

Phoebe DiPietro did not respond to a reporter’s email this week. In September, two days before DiPietro’s court appearance, Hanson released a statement from Reynolds calling for DiPietro’s prosecution, as well as Roberts’ and Elisha DiPietro.

“We respect the decication of the police agencies and the prosecutor’s office in pursing this case,” the statement said. “However, we disagree with the delaying arrest and prosecution.”

Phoebe DiPietro, Ayla’s paternal grandmother, said the same day in a statement to the Morning Sentinel that the case should remain focused on finding the child rather than pressing for criminal charges.

Last week, Phoebe DiPietro did not respond to a reporter’s email seeking comment.

At 29 Violette Ave. on Tuesday, a black car was parked in the driveway next to a big tree bearing a no-trespassing sign. A large sign displaying Ayla’s photo was replaced with two small green plastic flower boxes whose plants were blanketed in snow. A large teddy-bear shrine that had grown in the yard in the months after Ayla disappeared was gone.

In the cold afternoon, a large yellow cat sat on the DiPietro’s step, gazing.

At the house next door, John Roy was grieving the loss of his partner, Pati Redeagle, who died from cancer in August at age 61.

The couple, interviewed by the Morning Sentinel earlier in the summer about living next door to the house from which Ayla disappeared, had said they hoped the mystery would be solved, but they weren’t optimistic.

Roy said this week that strangers still drive by or walk through the neighborhood and stare at the DiPietro house. If Roy is outside, they ask him what he thinks really happened that night.

“I still get that all the time — a couple of times a week,” he said. “I tell them all the same thing: I don’t know any more than you do. I wish I did. I think it’s a cold case at the point. I wish I could resolve it but I don’t think it’s ever going to get resolved.”

Penny Rafuse, who lives a few houses east of the DiPietro home on the opposite side of the street, said the pain neighbors feel has not waned.

“I totally agree with law enforcement,” Rafuse said. “Someone in that house knows what happened to her on that night. They can run. They can hide. They can put up ‘no-trespassing’ signs on the lawn. It is just a matter of time.”

McCausland said police are still getting calls from people offering tips in the case. Early on, they asked that psychics no longer call, and that directive still stands, he said.

If people have essential information they have not shared, police want to hear from them, he said. He asked that they call 624-7076.

“If people have called in with information, they do not need to re-call,” McCausland said. “We can assure them that that information was tracked down, even though we may not have called them back.”

Amy Calder — 861-9247 acalder@centralmaine.com Twitter: @AmyCalder17

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story