TOGUS — But for a violent moment in 1986, someone once said, James T. Luoma has lived a remarkable life.

His story isn’t simple: A decorated, disabled Vietnam war veteran, he became a policeman and nurse while battling post-traumatic stress disorder. Later in life, he became a Pentecostal minister.

Now 63, he’s the head chaplain at VA Maine Healthcare Systems-Togus, a 500-acre campus outside of Augusta that is the oldest veterans’ facility in the U.S. and has a 67-bed hospital for general medical, surgical and mental health care.

Luoma was in a prison cell, he has said, when he found God.

On a July day nearly three decades ago, he shot and killed his 25-year-old wife, Sherry, at their Ohio home. That has never been disputed. He has maintained the shooting was an accident.

Details of past domestic abuse and cruelty while he was a policeman came out in his trial. After an initial murder conviction, Luoma got a new trial that resulted in a shorter sentence.

A decade ago, he left prison. He got ordained, started a prison ministry and began a career with the federal Department of Veterans Affairs, first in Dayton, Ohio. Luoma, whose nursing license says he lives in Fairfield, was hired to lead Togus chaplains in October.

Luoma declined to be interviewed for this story. However, a Kennebec Journal review of public records and news media reports unearthed biographical information on him, much of it told in his own words.

Officials at the Togus hospital said they couldn’t comment on Luoma or his hiring, but those in charge there probably didn’t know of Luoma’s crime because of an informational wrinkle in federal hiring policy.

David Rankin, who retired as Togus’ chief human resources officer in 2010, said the process is conducted in a way that probably kept hospital officials from seeing his federal background check — a VA hospital hiring someone who has already worked at one must rely on the first hospital’s check if the person is being hired for a similar position, and those checks in many cases can’t go back further than nine years.

A situation such as Luoma’s seems rare.

The Rev. Robert Certain, executive director of the Military Chaplains Association, a national support and service organization, said he hasn’t met a chaplain with a background like Luoma’s.

Rankin also said that during his career with the department, which included time at two other hospitals, he never found an employee with a past like Luoma’s.

However, he stopped short of saying there’s a problem with the VA’s hiring policies.

“I’m still enough of a civil servant to not criticize the process,” Rankin said. “As the young people say, ‘It is what it is.’”

Those who know Luoma say he’s a changed man since the shooting and deserves a chance in his new role.

“A lot of guys are nonreligious because of what happened in Vietnam — got wore out on God,” said Michael Stewart, of Washington state, who was in Luoma’s Army platoon in Vietnam. “If Jim’s done something to find his inner peace, good for him.”

TROUBLE ABROAD, AT HOME

Luoma dropped out of high school to join the Army at age 17. He wasn’t allowed in Vietnam until he turned 18. The private first class went there in 1968 as a combat medic.

Stewart remembers Luoma as “Doc,” a common name for medics. The job was dangerous. Luoma was injured twice before his combat duty ended violently in 1969.

Medics were responsible for going onto battlefields after fighting to check on American soldiers and enemies, Luoma told the Ohio State Nursing Board years later, according to a hearing transcript. His last time on a battlefield, Luoma said, he leaned down to check on a Viet Cong soldier.

It was a woman who had just lost both of her legs but was still alive and conscious. Then Luoma heard a distinct pop — the sound of a Chinese hand grenade.

He backed up; the grenade exploded. The woman was blown to pieces. The blast knocked Luoma several feet back, unconscious, with 67 pieces of steel in his knees, neck, groin, abdomen and back.

He recovered, served two more years in Oklahoma, then went back to Ohio and became a policeman, got married, then divorced.

Luoma rejoined the Army in 1975 as a drill sergeant, going back to Fort Sill, Okla., where he had served after his tour of duty in Vietnam.

All the while, he said later, he suffered from PTSD. He would wake up screaming from nightmares replaying combat scenes. Often he would get killed in those dreams. He left the Army again in 1978, going back to Ohio to take a police job.

He later said that during his law enforcement career, which ended in 1983, he helped jail about 2,000 felons; but there were also problems. His first wife, Paulette Blevins, later told police he used to beat her, and that’s why they divorced for good after two marriages.

Luoma was hired for another police job in 1979 but didn’t survive his probationary period, according to a 1993 Dayton Daily News article. Luoma’s personnel file said he left a prisoner jailed in handcuffs, kicked the legs of suspects before frisking them, searched a female shoplifting suspect without probable cause and fixed a traffic ticket.

Before getting hired to that job, a personality survey found that Luoma was “basically stable” but also “guarded and defensive,” showing “some anger and some anti-social feelings.”

In 1982, he was diagnosed formally with PTSD at the Dayton VA Medical Center’s mental health clinic. Around that time, he married Sherry for the second time — his fifth marriage, and his third wife. Luoma also decided to become a nurse around then, a nod to those who had helped him recover.

Problems remained: Sherry took out divorce papers and told a co-worker at a credit information company that Luoma had threatened suicide because of it, according to court records. Before then, she told a co-worker that when she told Luoma him she wanted a divorce, he left the room and came back with a gun, saying no one else could have her.

The same co-worker wrote to police that Sherry always had “the look of a trembling child, one that was scared but didn’t know what to do.”

Records also say that a male co-worker started dating Sherry after divorce papers were filed and she got a restraining order against Luoma. The man also reported that Luoma threatened him with both death and injury.

In 1985, Luoma graduated from Wright State University with a nursing degree and a 3.49 grade-point average.

However, he worked as a nurse for only about five months before July 31, 1986, when his then-estranged wife went to their house to talk. She brought Dairy Queen food for dinner. He had been showing his son how to load, unload and clean a shotgun.

‘IT WAS AN ACCIDENT’

Luoma has said Sherry was shot as he was moving the gun from the table to the counter. It went off accidentally just after she came in the door, he said.

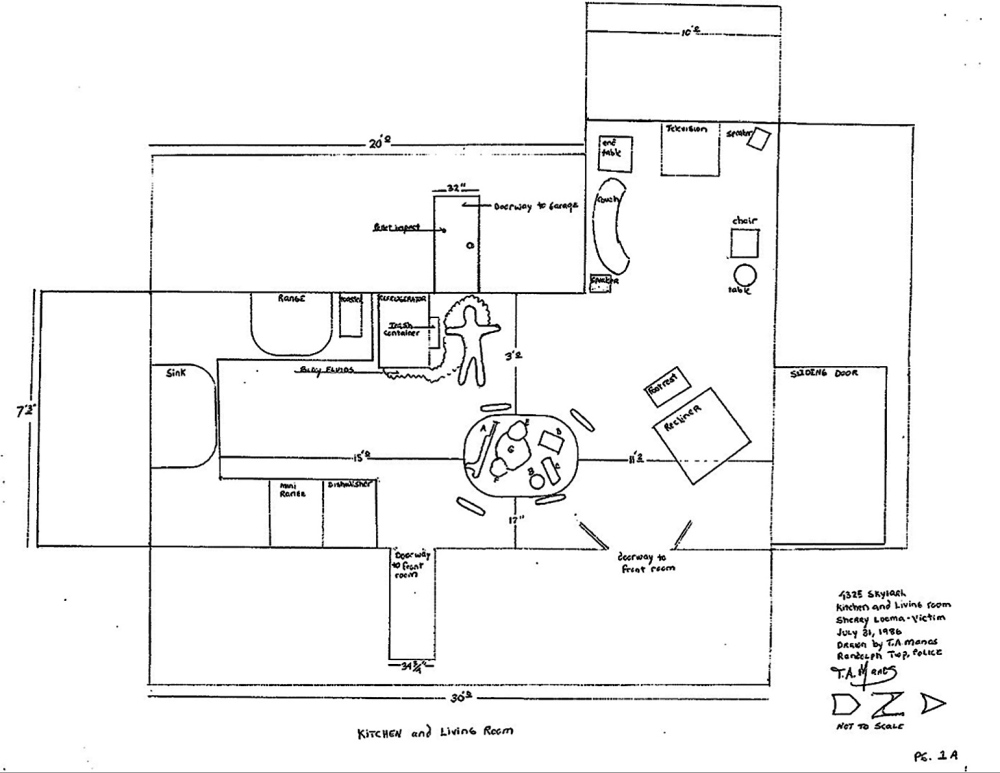

She died of a shotgun blast to the neck, falling just inside the door, court records say.

Luoma’s 16-year-old son from another marriage, James Christopher Luoma — Jimmy — was home at the time in another room. He later told police that his father had been acting in an “odd manner.” The day before, he said, his father told him he could kill someone without having the killing traced back to him.

The younger Luoma later told police that when Sherry walked in the door, his father grabbed and raised the gun. The boy said his father pulled the trigger in a joking gesture, the gun clicked and Sherry recoiled. Then the boy turned around and said he heard a gunshot.

“I yelled and screamed and accused him of killing her purposely,” Jimmy told police later that day. “I yelled and said, ‘You did it. You did it. I know you did it.’ Then he kept saying, ‘No, no, no, it was an accident. I’m serious. I’m serious.’”

Then, the boy said, his focus turned toward saving Sherry’s life. The elder Luoma called an ambulance and sent his son across the street to get a paramedic neighbor for help, but he wasn’t home.

Jimmy Luoma, now living at an Air Force base in Texas, declined to be interviewed for this story.

Police arrived at the scene to find Luoma with blood on his mouth and hands from trying to revive Sherry. He said at one point he felt a pulse, but she was pronounced dead at the scene.

He told police that he didn’t mean to shoot her and didn’t think the gun was loaded, crying during an interview with a police lieutenant.

“I’d rather (it) be me than my wife,” he said. “I love my wife, I, my wife was my whole life.”

Days later, police allowed Luoma to speak to his wife’s therapist, who told him that Sherry had been coming over to Luoma’s house to apologize for her infidelity. She planned to say she wanted to get back together.

Learning that made Luoma “feel extremely terrible, still does,” he told Ohio’s nursing board in 2004, “because I loved her very, very much.”

FINDING GOD IN PRISON

Luoma was indicted for murder, pleading not guilty by reason of insanity caused by PTSD. Suicide attempts and flashbacks to Vietnam were cited during his trial, the Dayton Daily News reported.

The prosecutor, Mathias Heck Jr., later said Luoma’s Vietnam experiences were no excuse for murder, particularly because he had abused his wife before, according to the newspaper.

That argument won out at first. After a 10-day trial in 1987, the jury was out 42 minutes before delivering a guilty verdict, Luoma told the nursing board in 2004. He was later sentenced to 15 years to life in prison.

That verdict didn’t stand, however, because Heck ran into trouble for his conduct at the trial. At one point, he told the jury that they would be sending Luoma home if he was acquitted because of insanity. In fact, he would have gone to a psychiatric hospital.

The verdict was thrown out and Luoma was re-sentenced in 1991, pleading guilty to manslaughter and getting sentenced to 10 to 25 years, plus another three years for using a gun.

Luoma alleged misconduct again in 1992. According to the Dayton Daily News, he made lurid headlines by filing civil lawsuits that claimed he had had a romantic relationship with his attorney, who won the appeal that got him a new trial. She was the wife of a judge Luoma said had threatened him with extension of his sentence or transfer to a high-security person because of the affair. The woman’s attorney, David C. Greer, wrote in a letter then that she had fallen in love with Luoma, but his rights weren’t violated, the newspaper reported.

Greer said recently that Luoma’s lawsuits were dismissed and the woman and her husband are still married. He’s now a senior federal judge in Ohio’s southern district; she’s a magistrate in an Ohio municipal court.

In a later account written for a prison ministry group, Luoma said when he went to prison, he was distraught and “believed that because I had turned my back on God and because of my crime that he had turned his back on me.”

Luoma felt that way until Feb. 28, 1994, at 7 p.m.

That evening, he was watching TV in his cell when Billy Graham, the televangelist, came on with Charles Colson. A former lawyer for President Richard Nixon, Colson did federal prison time for his role in the Watergate scandal. Afterward, he founded Prison Fellowship Ministries, the most notable prison ministry in America even today.

Luoma recounted going to the TV to change the channel. When he did, he began to cry. He said he listened to Colson, hearing “afresh and anew … how God had loved him and every prisoner.”

That made him drop to his knees and confess his crime and sins, he said.

“As I did so I felt a tangible release physically from the burden of sin and knew that I was forgiven, loved and totally cleansed of everything!” Luoma wrote.

By all available accounts, Luoma was a good prisoner for the rest of his stint. He later said he read nursing magazines and the Bible, and in 2001 he applied to an associate degree program offered in the jail. The professor told the nursing board in 2004 that Luoma got a 3.95 GPA before getting the degree in business administration — his single B grade being a result of surgery.

The deputy warden at his prison said Luoma clerked for him, performing typing and filing duties.

“You have two kinds of inmates you actually remember, the kind that cause trouble and the kind that don’t, and maybe that you would work with,” said Michael Sheets, a deputy warden at Madison Correctional Institution during Luoma’s stay, to the nursing board in 2004. “He was the kind that was no trouble.”

‘AN EXEMPLARY LIFE’

After 17 years and nearly six months, Luoma left prison. He later got a job at a gas station, completed parole and got aid from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to attend the seminary. He graduated from Cincinnati Christian University in 2008 with a master’s degree.

A 2004 decision by the Ohio nursing board also allowed him to keep his nursing license, despite the state’s argument that Luoma’s crime warranted full revocation of the license. During the hearing at which that was decided, Luoma gave a detailed account of his life before, during and after prison.

A state psychologist told the board that Luoma’s PTSD wouldn’t affect his interactions with patients and the public, though he recommended that Luoma not serve in an emergency room or in trauma situations. The psychologist said Luoma’s PTSD manifested itself internally, in the form of personal stress, nightmares and anxiety, but he had learned coping methods.

Michael Hardesty, the hearing officer in the Luoma case before the nursing board, sided enthusiastically with Luoma.

“It would appear that Mr. Luoma, but for one fatal second in his life in 1986 has led an exemplary life and overcome a myriad of (setbacks) through sheer determination and effort,” Hardesty wrote in a recommendation to the board.

Stewart, who served with Luoma in Vietnam and now volunteers as a veterans’ service officer in Washington state, wrote a letter of support for Luoma.

In a recent interview, Stewart said he also has PTSD and committed crimes upon his return home, serving a prison stint for drug smuggling before turning his life around. That’s why he wrote the letter.

“When Doc’s problems came along, I had a feeling for what happened,” Stewart said. “In my heart, Doc’s a good man.”

Luoma was allowed to keep his license, which is still active with restrictions. It was last renewed in October 2013.

In 2006, Ohio state records show, Luoma started Bearing The Burden Ministries, a nonprofit corporation that said its purpose was to give religious assistance to ex-offenders, the incarcerated and the hospitalized. The corporation had three officers: Luoma; his wife, Tracy; and another Ohio minister.

By 2011, he had a chaplain’s job at the Dayton VA Medical Center, where he worked until moving to Togus in October.

TOGUS LIKELY DID NOT KNOW

Luoma’s annual salary is more than $69,000, according to information provided by Togus spokesman James Doherty, who said hospital officials can’t discuss Luoma or his hiring, citing privacy issues.

But a provision in federal hiring rules, provided by Doherty, indicates that Togus probably didn’t know of Luoma’s conviction when he was hired, even though Luoma went through a background check years earlier when the government first hired him.

If an employee of one federal veterans’ hospital applies to a second hospital for a job that requires the same level of background investigation as the current job, rules say the second hospital must abide by the first hospital’s background check. It can’t conduct its own review.

Also, when a hospital determining a potential employee’s basic suitability for a job, only the last nine years of the applicant’s life are relevant. Jobs requiring higher access to sensitive materials than Luoma has are subject to more stringent checks. This means, in many cases, that prospective employees aren’t obliged to disclose a criminal conviction older than nine years.

So in Luoma’s case, the background check would have been conducted just after he applied for the Dayton job. His conviction would have been too old for him to be required to disclose it. Dayton VA spokeswoman Kimberly Frisco didn’t respond to a question about what the hospital knew of it and when.

If Dayton found out, Togus wouldn’t have seen that background check, according to Rankin, the former Togus human resources officer. He said Togus would have gotten his personnel file, which by law doesn’t contain the background check. Results of that would have stayed in Dayton, he said.

“I’m not making excuses for Togus, but I don’t think there’s any way they knew anything other than this was an employee who was cleared for suitability,” Rankin said.

Otherwise, past felonies alone don’t bar someone from getting a job with the federal government in many cases. For example, the veterans department’s website says it examines potential hires on a case-by-case basis, taking into account “the circumstances surrounding the conduct, the recency of the conduct, and the absence or presence of rehabilitation.”

Veteran candidates also get preference in hiring with the veterans department and other agencies. Disabled veterans — such as Luoma, who told the nursing board he was deemed partially disabled because of PTSD in 1982 — get an even higher preference.

‘GIVE THE GUY A CHANCE’

Some say the public’s response to Luoma’s crime and his current job will hinge on individuals’ belief in redemption.

“I think he’s come a long way,” said Stewart, Luoma’s former fellow platoon member. “I wouldn’t fear having Doc around me. He knows what triggered him and served his time for it.”

The Rev. Karen Swanson, director of the Institute for Prison Ministries at Wheaton College, an evangelical institution in Illinois, was Luoma’s teacher in a nondegree correctional ministry program he attended after leaving prison, remembering him as “a really good student and also very compassionate.”

She said he has had a consistent mission since leaving prison: helping people.

Ronald Brodeur, of Chelsea, adjutant of the Maine department of Disabled American Veterans, a service organization that works at Togus, said he has met Luoma only briefly since he got the job there, and he didn’t know about the crime.

After learning of it, Brodeur, also a Vietnam veteran, didn’t rush to judge.

“I’d say that everybody needs to be looked at for who they are and where they’ve been and what they’ve done, so I wouldn’t be making any judgments at this time,” Brodeur said.

But judgments could affect Luoma’s job, said Certain, of the Military Chaplains Association. Some veterans might shy away from confiding in someone they learn has killed a family member, and it’s “part of the long-term consequences you just have to live with” as a felon, he said.

Still, Certain, an Episcopalian who was a prisoner of war in Vietnam and now lives in Georgia, said hardship — be it as a soldier or prisoner abroad or at home — could inform chaplains, who must counsel a diverse group of veterans, many of whom have faced hard times of their own in or out of combat.

“Some of those folks may actually find a chaplain who has done murder as someone who can help them resolve their own sense of moral injury,” Certain said. “Who knows? I’d give the guy a chance.”

Michael Shepherd — 370-7652mshepherd@centralmaine.comTwitter: @mikeshepherdme@mikeshepherdme

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story