Sitting in a massive crane propped on the edge of a barge, Tim Kollman pulls a lever that lifts a clamshell bucket off the bottom of Portland Harbor. As the bucket rises, the entire crane swivels until the boom hangs over a hollowed-out barge called a dump scow. He releases the bucket’s contents, swings the crane back to position and lets the bucket drop to the water.

Kollman makes this same maneuver every 70 seconds. In one shift, he lifts up the bucket 300 times and digs up enough mud to fill more than five Olympic-sized swimming pools.

“You strive to be the best,” said Kollman, who works to keep the bucket moving as efficiently as possible. “The better you are, the more you work.”

Seven days a week, 24 hours a day, crews on the dredge barge are digging up the bottom of Portland Harbor, a $9.2 million project funded by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. They began digging Feb. 6 and won’t stop until March 25, when the bucket makes its last scoop in Casco Bay somewhere off Spring Point.

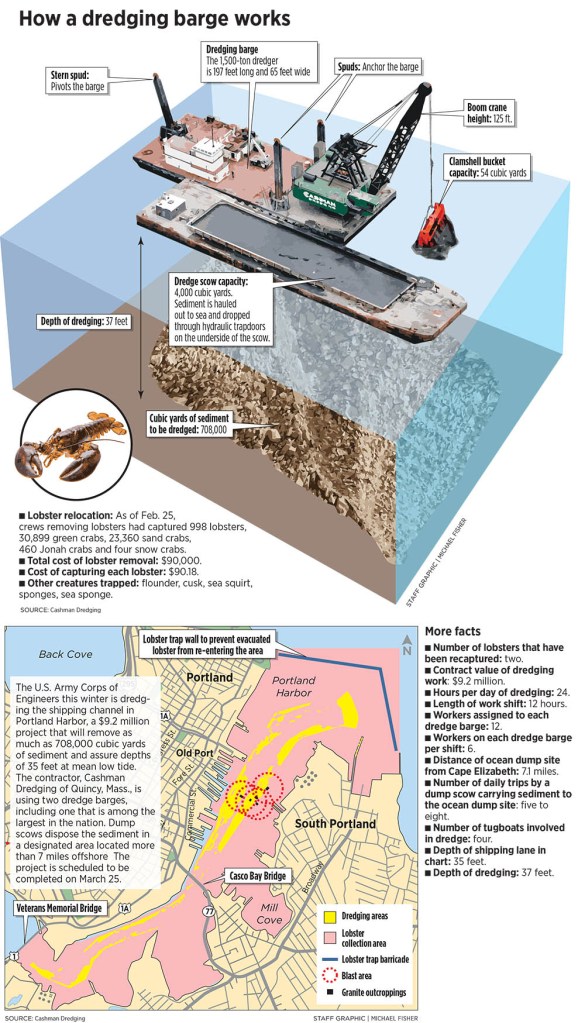

This is a maintenance dredge, meaning the goal is to maintain the shipping channel’s charted depth at low tide of 35 feet. Because the dredge bucket is not accurate, the crew is digging to 37 feet to make sure it doesn’t leave behind anything that could grab the bottom of a passing oil tanker.

The dredge barge, the Dale Pyatt, is one of the largest in the nation. With each scoop, its bucket picks up 54 cubic yards of sediment – enough to fill the beds of 27 full-sized pickup trucks.

There are 12 workers assigned to the barge. They work in 12-hour shifts, half at night and half in daylight.

Six other workers run a smaller barge, the F.J. Belesimo, which wields a smaller, heavier bucket with teeth. That barge, which operates only during the day, is used to tackle the hard-bottomed sections of the harbor’s shipping channel, while the Dale Pyatt grabs the soft clay and sand.

At the end of each shift, crew members are ferried home on a boat that drops them off at Rickers Wharf next to the Google barge, which hasn’t moved since it was towed into the harbor last October.

‘WALKING’ BARGE, MOVING LOBSTERS

The Dale Pyatt moves. It doesn’t have a propeller, though. It moves as though it was an old man walking with a cane.

The dredge has three legs, or “spuds,” which sink into mud and hold the dredge in place while the crane is digging. The dredge lifts its twin front spuds while a cable pulls the lone stern spud so it pivots at an angle and propels the barge backward. The crane operator uses the bucket to steer the barge, which can “walk” in only one direction.

The shipping channel runs between 400 and 1,000 feet wide, and the dredge digs in 80-foot-wide lanes mapped out on a computer screen that displays a color-coded view of the harbor bottom based on depth.

The dredge reaches the end of one lane, turns around and starts on another.

“We are basically mowing the lawn, if you will,” said Norman Bourque, project manager for Cashman Dredging.

Most of the dredging is focused on the edges of the shipping lane because ship turbulence clears out the middle and pushes the sediment to the side.

Four tugboats haul the four dump scows to a designated spot 7.1 miles east of Cape Elizabeth. There, hydraulic doors on their bottoms open up, releasing the sediment to the ocean floor about 200 feet below.

The digging only stops when the seas outside the harbor are too rough for the tugs to safely haul the dump scows.

In preparation for the dredging, since December a local two-man crew has been removing lobsters from the harbor and taking them to an undisclosed location on the other side of Fort Gorges. Using special traps designed to catch juvenile as well as adult lobsters, they must clear an area of lobsters before the dredge barge can start digging.

“The dredge is then free to come and follow us down the river,” said Lance Hanna, deputy harbormaster, who along with lobsterman Jim Buxton make up the lobster relocation team.

In 1998, the last time the harbor was dredged, crews removed more than 36,000 lobsters. But the trapping was done in the early fall. By the time trapping began this year, most of the creatures had already relocated themselves by crawling out of the harbor to deeper water, which is warmer in winter. As of Feb. 25, Hanna and Buxton had captured only 998 lobsters.

The lobster removal project, designed to protect the lobster fishery, cost $90,000, which is split three ways by the Maine Port Authority and the cities of Portland and South Portland. If no more lobsters are trapped, it will have cost $90.18 to relocate each individual lobster.

Because of the high cost, the lobster removal idea will be reconsidered the next time the harbor is dredged, Hanna said.

BLASTING NEEDED TO BUST GRANITE

Besides mud, sand and the occasional lost lobster trap, dredge crews also have removed 1,550 cubic yards of rock from the harbor

Crews on another Cashman vessel, a drill boat called the Kraken, last month drilled holes into granite outcroppings in the shipping lane, packed them with explosives and blasted. The granite is located in the shipping lane in five spots. Although the ledge was about 35 feet below the surface, sediment over time would build them up. So the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers called in the Kraken.

An odd-looking vessel that has three drill towers, the Kraken is named after a legendary sea monster that is said to dwell off the coasts of Norway and Greenland.

The Kraken lived up to its name in Portland Harbor. Each blast was actually multiple explosions set off in rapid succession in a linear pattern. The explosions were muffled by the water. Shock waves from the blasts created a low, fast-moving wave of foam, the kind a sea monster might make while swimming just below the water’s surface. Watch a vide of the blasting here.

Fish killed by the blasts floated to the surface and become quick meals for sea gulls. In New York Harbor, where the blasting occurred much more frequently during a recent dredge project, the gulls would swarm the Kraken whenever they heard the alarm announcing the one-minute countdown that preceded each explosion. Portland’s gulls never figured out that trick.

Before the blasting began in Portland, residents in the condominiums on Chandlers Wharf were anxious about the blasts, and some tried to stop them. They can now relax. The Kraken left the harbor Saturday morning.

At the end of this month, the rest of the dredging crew will leave Portland and move on to New Haven, Conn. There, they will dredge a harbor clogged with sand and sediment stirred up by hurricanes Sandy and Irene.

This is their life, traveling from harbor to harbor and up and down the nation’s waterways. The lifestyle is fun when one is young, but gets harder when their children grow old enough to attend school, crew members say.

The money is good. Kollman, for example, earns more than $36 an hour as a licensed crane operator, the highest-paid job on the union scale. But he misses his 10-year-old daughter back home in Pennsylvania.

He took some time off last week to be with her on her birthday. He then headed back to Portland to start digging again.

“She still cries when I leave,” he said.

Tom Bell can be contacted at 791-6369 or at:

tbell@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.