Monday was Opening Day, and we were reminded yet again that baseball is America’s national pastime. It’s hard to imagine a time when baseball wasn’t considered the national game, but long ago another sport was far more popular: competitive walking.

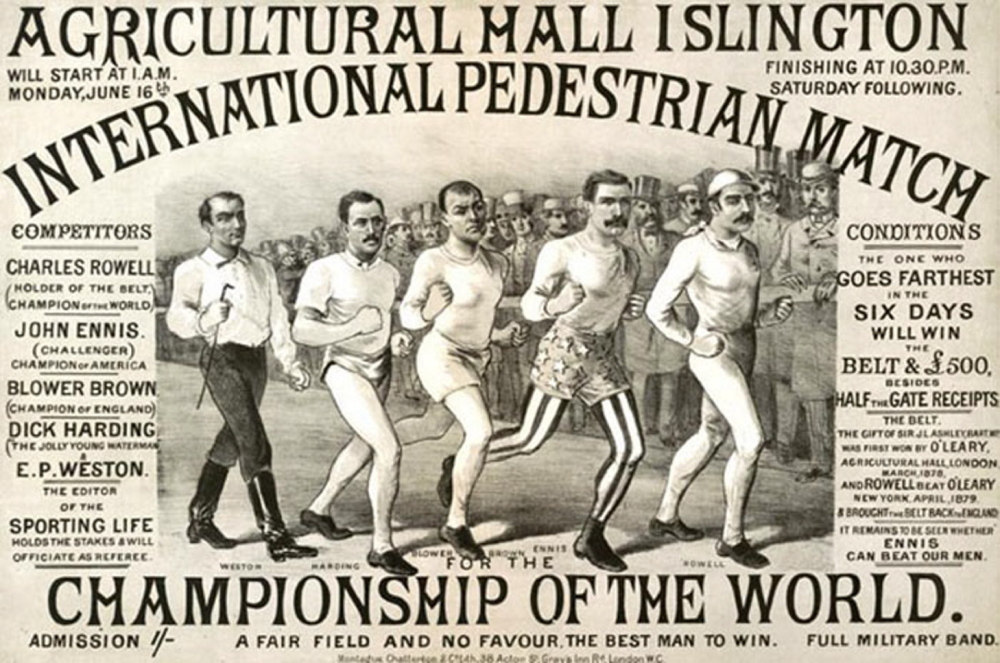

In the 1870s and 1880s, the country’s largest arenas were packed to the rafters with fans watching men — and sometimes women — walking in circles on dirt tracks. They raced around the clock for six days at a time. (Prohibitions on public amusements on Sundays made longer races impossible.)

Although running was sometimes allowed, it was not an effective strategy for races that lasted 144 hours straight — roughly the length of 50 baseball games. Stopping occasionally to catch a few winks on cots placed on the arena floor, the competitors pushed themselves to, and sometimes beyond, the edge of physical and mental collapse. A nation starved for entertainment in the days before radio and record players savored the competition.

The sport was known as pedestrianism, and its most successful practitioners were this country’s first celebrity athletes. Their images appeared on some of the first trading cards, and they received lucrative endorsement deals. Dan O’Leary, an Irish immigrant from Chicago who won a six-day race by walking 520 miles, was the spokesman for Dittman’s salt. Another pedestrian, John Hughes, was sponsored by the National Police Gazette. During races Hughes wore a shirt with the newspaper’s logo emblazoned across the front, one of the earliest examples of advertising on an athletic uniform (a trend that, to its credit, Major League Baseball has resisted).

Champion pedestrians were well paid. After a six-day race at Madison Square Garden (then known as Gilmore’s Garden) in March 1879 — attended by luminaries including James Blaine, who was then a Republican senator from Maine, and future president Chester Arthur — the winner, Charles Rowell, walked away with more than $18,000 (about $425,000 in today’s money). Not bad for six days’ work.

But just a decade later, pedestrianism was dead. By then, charges of race fixing and doping had diluted fan interest. During one race in 1876, the famous pedestrian Edward Payson Weston was caught chewing coca leaves — a practice that was considered unsportsmanlike, if not outright cheating.

Meanwhile, baseball was on the rise. The National League, founded as a ragtag enterprise in 1876, became a stable, profitable business after team owners imposed a $2,500 salary cap in 1885. Of the eight clubs in the league in 1890, only one, the Cleveland Spiders, no longer exists. The other seven clubs were, and still are, the Braves, Cubs, Dodgers, Giants, Phillies, Pirates and Reds. Fans who once had flocked to six-day races instead filled spacious new wooden ballparks.

For all its popularity today, baseball would do well to remember the demise of its predecessor as America’s favorite spectator sport. Players’ use of performance-enhancing drugs has sullied baseball’s image. TV ratings are declining.

For a brief time, it seemed that pedestrianism would be our national pastime forever. Even if it takes more than a century, history has a way of repeating itself.

Matthew Algeo is the author of “Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport.” This column was distributed by The Washington Post, where it first appeared.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.