WATERVILLE — A tussle over a library renovation at Colby College has sparked a debate about the role physical books still play for library users in an increasingly digital world.

About a year ago, thousands of books began to be transferred from their shelves at Colby’s Miller Library to a storage building built for that purpose, part of a $12.3 million renovation project that also brought new programs and study spaces into the library.

The renovation, which is scheduled to be completed this summer, drew complaints from students and faculty in part because stacks of books — about 40 percent of the library’s total collection — were put in storage off campus, where they are retrieved twice per day at the request of library users.

A group of 76 faculty members have signed a series of petitions against the renovation, while administrators have continued to move forward with the project. In an open letter from faculty published April 10 by the Colby Echo, the campus newspaper, they called the renovation “hurried” and “poorly thought-out” and say teaching faculty have been “overwhelmingly excluded from decisions about how to build and staff a better library.”

Under the current plan, the new library will include scores of large open spaces filled with group study spaces, as well as office spaces for Colby’s academic information technology department, a writing program and a center for the arts and humanities.

“We think we can make the Colby library a place for reflection and hard work without having huge open spaces as the first step,” Paul Josephson, a history professor who signed an open letter protesting the renovation, said Monday. “Many people feel that there need to be study areas, but people who signed the letter believe we’ve moved a little too quickly and it’s best to preserve more of the stacks. I believe the written word is still the wave of the future.”

At issue is what role the library will play in the future of the college.

“We brought into the library units that we think of as partners in both teaching and learning,” said Lori Kletzer, vice president for academic affairs and dean of faculty at Colby, who referred to the conflict as a “clash of visions.”

“We wanted to expand that symbolically, to symbolically have the library, yes as a place with books and also a place for people and programs to come together in this collaborative learning environment,” she said.

Faculty who have protested the project complain that the absence of the books and the introduction of wide open group spaces have transformed the atmosphere of the library into a place that discourages serious study.

People from both sides cited the importance of books as a reason for their position.

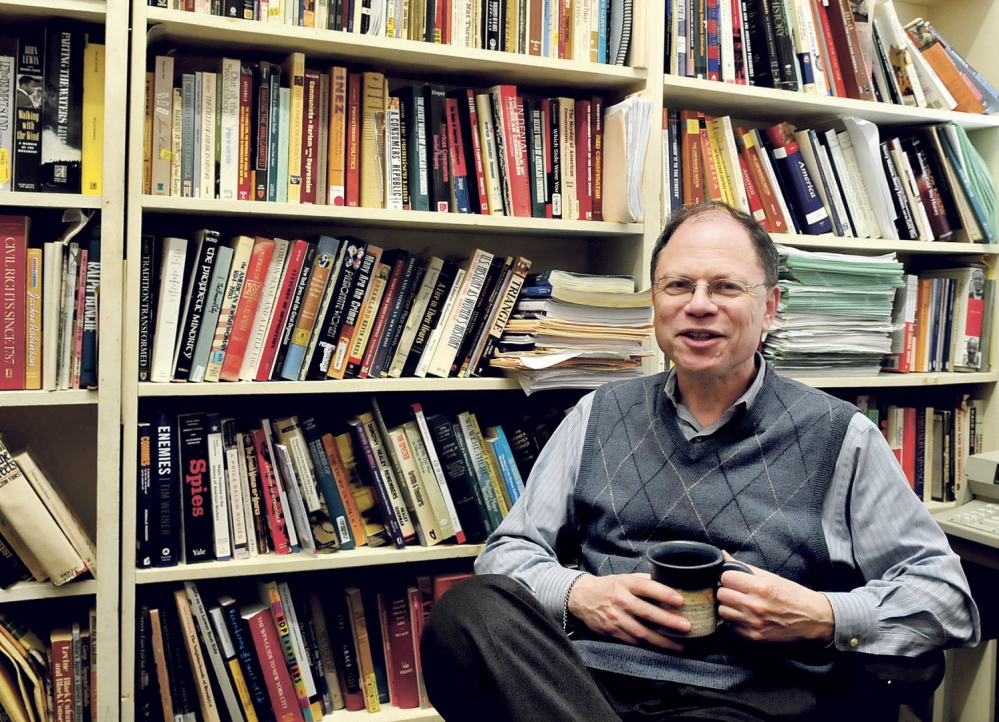

For Robert Weisbrot, a professor of history, physical books arranged by subject are important in part because the act of browsing through them can expose a researcher to different angles and ways of thinking about their subject.

“I can tell you that the loss of books has hurt my teaching,” Weisbrot said. “It’s hurt my students’ research. It’s hurt my research.”

Weisbrot said that seeing books clustered in a particular section, and browsing through their contents, is an integral part of research that needs to be preserved.

“I see other books on the same subject, some written earlier and some more recently, presenting perspectives that suggest how our thinking has evolved over time,” he said.

But Kletzer said a love of books isn’t a reason to reject the renovation — it’s a reason to embrace it. The renovation was needed, she said, because the Miller Library no longer has enough room to house its collection, which grows by about 8,000 titles a year.

“We now have storage space for decades into the future,” Kletzer said. “If we had not built a storage facility, we would have had to reduce our collection.”

When the library was last renovated in 1983, it was designed to accommodate the growing collection into the late 1990s. Now, Kletzer said, the library is able to meet its demands for another 25 years.

“I fully respect my colleagues differing point of view, but where we do not differ is this valuing of the book and the value of the Colby collection,” she said. “I grew up in those stacks as well. There are still stacks in the library. You can still get lost in the stacks.”

Josephson said the space could be allocated in a way that better balances books and other uses of the library’s space.

“I don’t know what percentage of space is for stacks, but my sense is it could be much more without losing those other uses the dean is referring to,” he said.

Digital collections have added another dimension to an ever-shifting idea of what belongs within a library’s walls.

“Many libraries, small colleges as well as large, have moved to retrieval storage,” Kletzer said.

Nissa Flanagan, president of the Maine Library Association, said Americans are embracing digital resources but not at the expense of traditional books.

“We have not seen a decrease in circulation of our print materials,” said Flanagan, who also works at Merrill Memorial Library in Yarmouth. “But we have seen an increase in our electronic circulation.”

In a Pew survey, 96 percent of Americans said libraries are valuable because they provide access to technology-based resources, but only 4 percent said they read electronic books exclusively, according to the 2014 State of America’s Libraries report of the American Library Association, which was published Monday to mark National Library Week.

Flanagan said technology has provided new opportunities, but remains a complicated and costly aspect of curating a collection of books.

Publishing companies charge libraries much more for electronic books than they charge consumers. Some have even sold copyrighted material that expires after a set number of viewings, which would mean libraries would have to continually repurchase materials.

“We’re working hard and trying to figure it out,” she said.

Flanagan noted that in public libraries, the idea of individual consumers browsing the stacks is a relatively new development that only became commonplace within the last century. Before that, most libraries operated on a retrieval system similar to the one being partially implemented at Colby.

She said the right answer to any adjustment is specific to the collection and user base of a particular library, but that it is rarely a simple matter.

“Change is hard,” she said.

At Colby, administrators and faculty have said they each respect the opinion of the other and hope to arrive at a resolution.

“I have tremendous respect for that passion that my colleagues bring to this,” Kletzer said. “I know that passion comes from their very deep commitment as teachers and scholars. Colby is a place where we can openly express differences of opinion.”

Faculty said they are motivated by a concern for the place that books have in the society of future generations.

“So far, the advance in technology has been wondrous and I have availed myself of it. All of us as faculty members have been thrilled with all of the advances,” Weisbrot said. “But to this point books have proven irreplaceable and invaluable.”

In the faculty’s open letter, they call on Colby officials to not “throw good money after a bad idea,” saying the library renovation poses “significant danger to Colby’s reputation as a leading liberal arts institution.”

Josephson said recent moves by administrators to include more faculty input into the project are positive, but said it has to be a first step in an ongoing process.

“We’re concerned about preserving the sanctity of the book in the 21st century,” he said.

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287 mhhetling@centralmaine.com Twitter: @hh_matt

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story