OAKLAND — In front of a T-Mobile call center, at the cornerstone of the business park, is a four-way intersection with two options leading nowhere, roads ending in thickets of trees.

The call center employs around 600, jobs that some say were worth the millions of dollars that area taxpayers have poured into FirstPark over the last 15 years.

“It kind of validated the rationale of why we needed to invest in a facility like that or a project like that,” said John Butera, who served as executive director of the Central Maine Growth Council when FirstPark landed T-Mobile in 2004 and now serves in Gov. Paul LePage’s administration. “It’s a long-term investment.”

But there are only about 200 employees in the rest of the park, scattered among less than two dozen small medical offices and financial firms. On paper, the investment hasn’t come close to paying off for the 24 central Maine communities that invested in FirstPark.

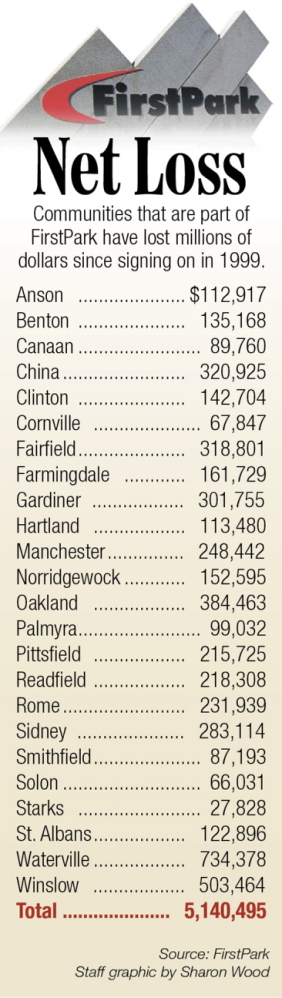

Cities and towns had lost a total of $5.14 million on it as of last July, largely to pay off borrowing that funded the park’s construction. Some tax revenue is returned to them annually, but they got back only 40 percent of what they paid in last year.

Jobs at the park — the reason the communities say they joined to fund the development — have remained stagnant since 2006, when T-Mobile opened the call center. In 2011, a third of the jobs at the call center were held by people living in municipalities that didn’t buy into the park.

However, original proponents of the project, including city and town officials, argue that the lack of lot sales and job growth is the result of the larger economy and that the forming of the park’s governing body devoted to economic development in the region, the Kennebec Regional Development Authority, is a victory in itself.

Although not all city and town leaders see the value of being members of the authority, there appears to be growing hopefulness that a fresh direction from the park’s fourth executive director, Brad Jackson, who took the reins a year ago, will result in the region attracting more of the 3,000 jobs promised by the project architects 15 years ago. Still, without any successes since T-Mobile, it’s difficult for some residents and community leaders to see the value of their investment.

“At this point, the citizens and community of St. Albans don’t feel like they’ve gotten what they’ve been told they’d get out of it,” St. Albans Town Manager Rhonda Stark said. “They signed up thinking great things were going to happen, and it hasn’t happened.”

She said the town, about 35 miles from the park, has been trying to get out of the investment ever since it joined.

The city of Gardiner’s representative to the authority general assembly, Nate Rudy, advocated at the last two annual budget meetings that the park reduce its budget out of respect for the financial challenges faced by municipalities. Both times he was the only municipal representative to vote against the budget; but this year, in February, the town manager of Fairfield also voted to not send the budget to the general assembly.

Rudy said he thinks there are areas in the budget that could be reduced, and it doesn’t appear the park leadership understands the communities’ needs. The authority was created to provide economic development to the entire region, and it hasn’t done that to date, he said.

Rudy said a recent proposal to use surplus revenue to pay the Central Maine Growth Council — another economic development group representing Fairfield, Waterville and Winslow — to conduct business outreach and other proposals to sell additional economic development makes him question whether the park leadership is representing the municipalities’ interests.

“Either provide member communities with more value or reduce our expenses; but just to say, “Well you all signed this agreement, and if you don’t like it, too bad; quit your complaining,’ that seems a bit untoward,” Rudy said.

In Readfield, about 25 miles from FirstPark, Town Manager Stefan Pakulski said the idea of towns and cities in a region joining together to attract economic development opportunities was a good one, but it’s difficult for the townspeople to see how the park has helped them.

“There’s no tangible, direct, visible benefit that people say is happening in Readfield,” he said. “I think I heard that maybe one time there was a resident that was employed up there at one point. I don’t know if they are anymore.”

Pakulski is hopeful that the park and the development authority eventually will provide the jobs and economic boost to all of the region, especially under Jackson’s new leadership, but he said it’s not clear whether the park will ever deliver on its promises.

“This was a decision made out of optimism — hopefully not hubris, but certainly a decision not made it out of fear. It was a decision made to do something positive,” Pakulski said.

TOUGH GOALS TO MEET?

When one looks back at the feasibility study conducted by New Hampshire-based RKG Associates in 1998, the jobs and revenue projection appear very optimistic in retrospect.

The financial projections presented to residents of the member towns and cities as part of the pitch for the park showed they could expect to see positive yearly returns by 2004 and a total net return of $700,000 this year. Instead, communities paid out almost $600,000 this year.

The projections also anticipated communities would recoup their entire investment by 2009. Those projections also included another $6.5 million in bonds for a complete build-out of the park that were never taken out because of the lack of business interest.

Although the addition of T-Mobile in 2006 pushed job totals ahead of projection at the time, the totals have remained mostly flat since. The study anticipated the park would have created more than 2,000 direct jobs by this year and 3,000 by the end of the 20-year investment.

However, Steve Levesque, the commissioner of the Maine Department of Economic and Community Development at the time the authority was created, said recently that the job projections should be viewed in the context of when the study was done. Since then, advancements in technology have lowered the number of employees needed for many jobs, he said.

Waterville City Manager Michael Roy said he thinks the two unforeseen events — the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, and the Great Recession through all of 2008 — stunted the park’s development.

“When this park was proposed, two things were made clear: It’s a 20-year project and it’s a risk. There are no guarantees that we will fill the park up as quickly as we’d like, but we set goals,” he said.

Roy, who was Oakland’s town manager at the start of the project, said that although he thinks they might have overestimated the demand for this type of development, it’s too early to say the park hasn’t been successful.

“We still believe in the viability of it. We’re still committed to making it a success,” he said. “We have an uphill battle for the remaining term of the contract, but we still believe it can be a job creator for the area.”

SUCCESS FROM COOPERATION

Efforts that led to the creation of the development authority and FirstPark began in the 1990s with meetings between the Kennebec Valley Chamber of Commerce in Augusta and the Mid-Maine Chamber of Commerce in Waterville.

Craig Nelson, the president of the authority and one of the project’s architects, said the Augusta and Waterville groups historically had been rivals, but they began meeting in the mid-1990s to try to find ways to work together on economic development.

The communities were seeing mills struggling or closing, so the members thought, “You know, we need to do something to try to pick this area up by the bootstraps,” said Nelson, in an interview in his Augusta law office earlier this month.

They formed a new entity called “The People of the Kennebec” to champion some type of regional development effort. Levesque, now executive director of the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority in Brunswick, suggested developing large, regional business parks to bring new companies to the state.

Levesque said many individual towns and cities were building their own industrial parks at the time, but the parks didn’t have the necessary capital or infrastructure to succeed. The goal was to build several of these “superparks” across the state instead of dozens of small community parks, he said.

Then-Gov. Angus King jumped on board with the idea, and the Legislature passed a bill in April 1998 creating the authority.

“From the time it had its public hearing and the time the governor signed the bill, I think was less than two weeks. It just went,” Nelson said, slapping one hand quickly across the other. “Everybody thought that was a really good idea.”

The state offered a $1 million Community Development Block Grant for communities that were able to work together to develop one of the parks. However, only the Kennebec authority succeeded in rallying the regional support needed. After King left office at the start of 2003, the idea for more “superparks” fell by the wayside.

Even FirstPark didn’t attract as many communities as originally targeted. Some, notably Augusta, decided to not join because they were concerned about the upfront costs or questioned the project for other reasons.

Residents in Augusta rejected joining the authority, 976-560, in a citywide referendum.

City Manager William Bridgeo said he thinks it was rejected because of the uncertainty about such a long-term payback period and the feeling that the roughly $100,000 requested to join the authority could be spent better on economic development inside the city.

“Not to say that regional cooperation isn’t a good idea,” Bridgeo said. “I think that idea of municipalities banding together to do something collaborative, pooling their resources together, had merit then and has merit now.”

In the end, 24 communities — 12 in Kennebec County and 12 in Somerset County — agreed to invest in the park.

“A lot of people have asked me on and off over the years, why did those 24 towns vote the way they did?” Nelson said.

Since he and Levesque both lived in Farmingdale, they gave the presentation to their town, Nelson said. He recalls picking out around two dozen parents with children who had graduated with his children but had taken jobs out of state. The business park, he told them, would allow young people in the area to stay in Maine.

“It was about jobs — not just current jobs, but more jobs for our children and future generations. That’s what the votes were all about,” Nelson said.

Some supporters of FirstPark say that although it hasn’t yet reached the number of jobs originally projected, T-Mobile’s decision to open its call center there makes the project a success.

However, T-Mobile locating in FirstPark led a major Maine company to drop its plans to open a similar operation there.

L.L. Bean already had purchased two lots and begun initial construction on a 50,000-square-foot call center to replace its Waterville location, when T-Mobile surprised everyone with its announcement. Three days later, the outdoor retailer dropped its plan for FirstPark because of concerns that T-Mobile would dry up the workforce needed for its plans to supplement its 220-year-round employees at the facility with hundreds of seasonal workers.

Speculation and fear that L.L. Bean would move its Waterville call center out of central Maine — or out of Maine completely — prompted then-Gov. John Baldacci to meet with company executives to assure them of the viability of the region’s labor market. In March of the next year, L.L. Bean announced its commitment to keep the call center in Waterville open.

Five years later, the retailer closed the Waterville call center, citing high costs and challenges associated with operating the call center in the mall plaza.

L.L. Bean still owns the two lots in FirstPark.

NEW DIRECTOR, NEW STRATEGY

Jackson, FirstPark’s executive director, said he’s taking a different tack to business attraction than what had been done before.

Instead of focusing on passive advertising such as print, he said he’s trying aggressively to get in front of decision makers at growing companies to pitch central Maine and not just the park.

Jackson said a regional strategy, like what was originally envisioned with the creation of the authority, is necessary because the business park isn’t close to a major city such as Boston or even Portland. There’s no real demand for office space with high-end infrastructure and facilities, he said.

That’s why Jackson said he is pitching the entire region to prospective companies. If other locations or business opportunities would make more sense for the companies, Jackson will connect the companies with other parties in the region, he said.

“This park will not develop in isolation. It will advance when the region advances,” he said.

Jackson said he understands the frustration of communities that still haven’t gotten a financial return on their investment. The business model didn’t work as projected, but it still makes sense, he said.

The legislation to create the authority allows cities and towns to leave the authority only after it turns a profit. Even then, the communities still will be on the hook for any outstanding debt. The current bond is expected to be paid off in 2021.

The original plan called for the cities and towns to take on another $6.5 million in bonds to fund the five construction phases over the 20-year period, but Jackson doesn’t anticipate that happening anymore. The build-out for the rest of the park’s six lots is now estimated to cost $3.8 million, and Jackson said they’ll try to use any future business developments to help fund it.

He didn’t express concern about whether communities would try leaving after the debt is paid off.

“I’m hoping by that time, I would have demonstrated the value of my approach and that it’s something worth paying for,” Jackson said.

The strategy hasn’t resulted in any definitive prospects yet, but Jackson said the companies he’s targeting will be looking to expand within the next year or two. He anticipates making presentations to around 30 companies this year.

A pharmaceutical company from New York toured the park last spring, he said, and executives there could make a decision about expanding in the next year to bring about 150 jobs to the park. He has also visited companies in New Brunswick last fall, and he was in Quebec province last week to make more pitches.

“Judge me in three years from now,” Jackson said.

Paul Koenig — 621-5663pkoenig@centralmaine.comTwitter: @paul_koenig

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story