Portland officials are stepping up their efforts to fight FOG – the fat, oil and grease washed down kitchen drains that clog city sewer pipes and accumulate by the ton at treatment plants.

Several months after groups began raising awareness about clog-inducing bathroom “wet wipes,” city officials have launched a new campaign to reduce the amount of grease and fatty materials dumped down drains from homes and restaurants.

The campaign to reduce grease buildup rather than deal with the messy aftermath is part of a pollution-reduction plan developed with federal regulators.

“It’s always been an issue, but we have dealt with it [in the past] primarily at the pumping stations,” said Bradley Roland with the Portland Public Services Department’s engineering division.

Like many cities, Portland is under pressure from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to improve how it handles wastewater in order to prevent raw sewage from ending up in local waterways. In addition to spending more than $100 million on sewer infrastructure, the city is increasingly focusing on fats, oils and greases, or FOG, that can obstruct sewer lines and cause waste to back up into streets or homes.

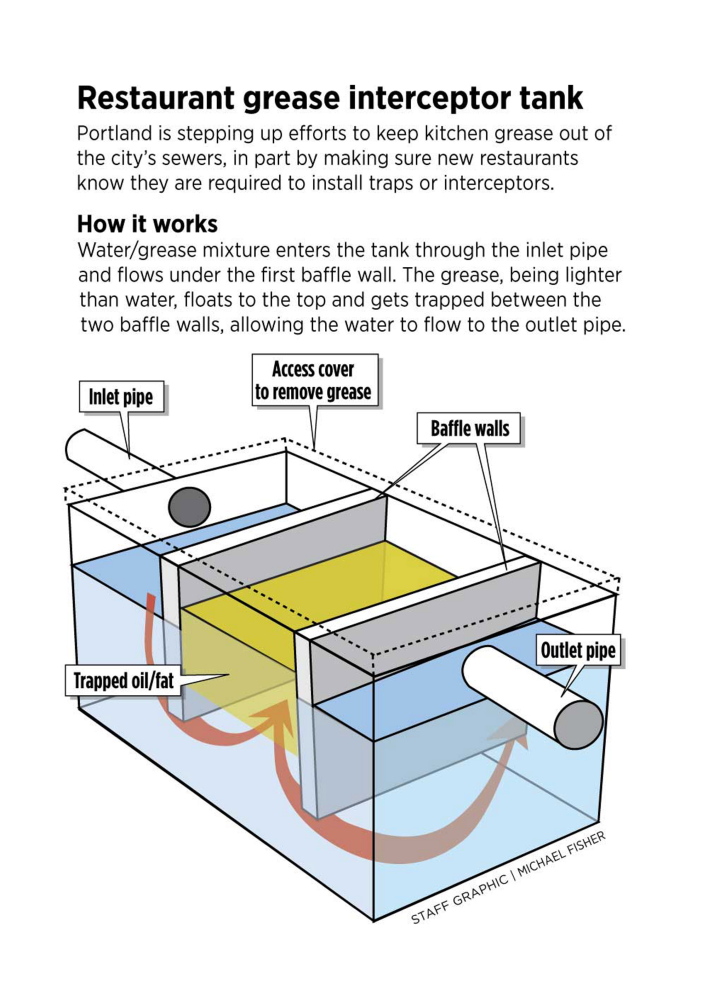

Beginning in December, the city’s Public Services Department began notifying applicants for restaurant licenses early on in the process that they would potentially have to install grease-collection systems.

Such systems – which can run between $4,000 and $10,000, depending on the size and location – have been required for new restaurants or major modifications for years. But some restaurant owners did not learn about the requirement until late in the review process, while other projects may have slipped by because they were not large enough to trigger a site review.

The FOG collection policy does not currently apply to existing restaurants, although Roland and Public Services Director Mike Bobinsky said an expansion is likely in the future given the number of restaurants in the city.

“We are known as a sort of foodie town. We love our restaurants,” Roland said.

Cleaning up excess FOG buildup in a city or town’s infrastructure is a messy, time-consuming and costly affair. Last year, officials in London had to clean out a 15-ton lump of grease and “wet wipes” that became so famous that locals dubbed it “fatberg.”

While Portland has yet to see a grease clump large enough to name, the city’s restaurants, homeowners and businesses generate plenty of grease.

In 2013, Portland Water District employees removed roughly 70 tons of the greasy mess from the district’s pumping stations and treatment plant, costing the city more than $60,000.

Every few months, the massive accumulation of grease at the treatment plant is scooped up with a backhoe and loaded into trucks for disposal at ecomaine’s facility. The gunk can also contribute to odor problems at the facilities and will clog pipes if they are not maintained regularly.

Scott Firmin, director of wastewater services at the Portland Water District, said workers must clean the sludge treatment lines at the treatment facility weekly by flushing them with hot water, a process that takes time and costs money.

“I can’t tell you what it costs to do it, but I can tell you we have to do it to keep things going efficiently,” Firmin said.

The city also has a list of more than a dozen streets and nine pumping stations that require at least semiannual cleaning because of past problems with FOG buildup at the sites.

City officials are also planning a public educational campaign urging residents to collect fats, greases and oils in containers for disposal in the trash rather than down the drain. They are also urging residents to wipe excess grease out of pots and pans – and then dispose of it in the trash – before washing.

The anti-grease campaign comes on the heels of a “wet wipes awareness campaign” waged by the Portland Water District, the Maine Wastewater Control Association and an industry trade group.

Although marketed as flushable, the increasingly popular wet wipes can clog in wastewater treatment facilities as well as in sewer pipes, especially when combined with grease.

The groups’ awareness campaign, which included signs on supermarket shelves and “don’t flush” reminders on checkout receipts, recently received an “environmental merit award” from the EPA.

Firmin said they are still evaluating whether the campaign made a difference, but he is optimistic that Portland-area residents are thinking twice before flushing the wipes.

“The initial numbers show there has been a decrease,” Firmin said.

Kevin Miller can be contacted at 317-6256 or at:

kmiller@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story