Frank Hillman has been trying to sell his building in downtown Gardiner for three years, and around two months ago he thought he had found a buyer.

But that was before the developer heard the quote for flood insurance on the property.

The buyer expected to pay about $2,000 a year for flood insurance. The actual price tag: nearly $20,000.

“That quote literally made everything come to a screeching halt,” said Dustin Slocum, the Brunswick-based developer hoping to purchase Hillman’s building to house the Gardiner Food Co-op.

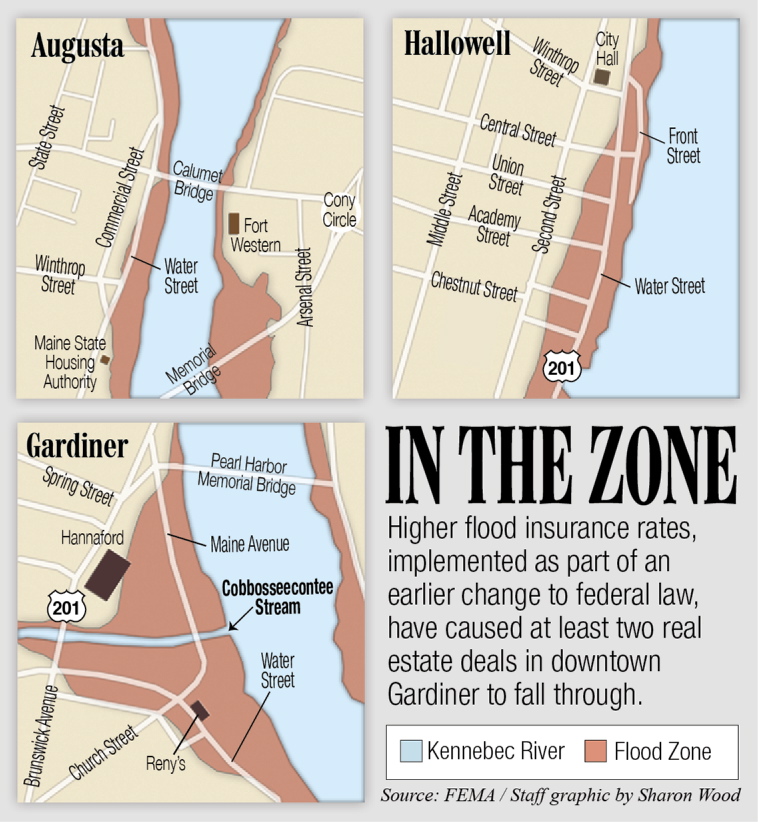

It’s at least the second real estate sale in downtown Gardiner that fell through this year because of high flood insurance premiums caused by a federal law passed in 2012 to try to return the flood insurance program to solid financial footing.

Although lawmakers updated the law in March to halt most of the steep increases, the subsidized rates for older buildings in the floodplain are still expected to slowly increase until they reflect the actual risk of the properties. Buildings receive subsidized rates if built before the end of 1974 or before the community adopted its first flood map. Most towns and cities in Kennebec County first adopted flood maps around 1980 or later.

For properties well below the floodplain, such as Hillman’s and the rest of the downtowns of Gardiner and Hallowell, those deal-squashing rates could be the new reality in less than two decades if the Federal Emergency Management Agency increases them as much as the new law allows and if nothing is done to mitigate the flood risks.

ANOTHER DEAL DOOMED

An insurance agent in Augusta who provided a flood insurance quote that led to the unraveling of another real estate deal in downtown Gardiner, Ryan Madore, said he doesn’t expect premiums to continue to rise that much.

Madore, a senior account executive at United Insurance, said the building for sale on Water Street in Gardiner had a flood insurance quote of roughly $2,700 annually in 2012. The quote for that same property jumped to $26,000 for a prospective buyer this year because of the 2012 law.

Now, after the recent changes returned the subsidies starting May 1, the annual premium for flood insurance is $2,200.

He said he doesn’t think FEMA will raise the rates that much again because it would be impossible to operate or purchase downtown buildings with such high increases.

“That was my major concern,” Madore said. “Whether it’s Hallowell or Augusta or Gardiner, every community that I know of is working so hard to rejuvenate and bring business to their downtown, and it’s certainly a major issue to have flood insurance premiums get that astronomical. It becomes cost-prohibitive to own any property downtown.”

However, the state coordinator for the federal flood insurance program said it’s not clear from the guidance provided by FEMA how much flood insurance rates will increase for subsidized properties.

“We’re definitely going to have to be watching this,” said program coordinator Sue Baker.

Flood insurance is required for buildings in the floodplains with mortgages. It’s not required once the mortgage is paid off or if an owner purchases with cash or gets private financing from the previous owner.

More than 35 percent of the roughly 9,200 flood insurance policies in Maine receive some type of subsidized rate, according to Baker. Most of the roughly 3,300 of the subsidized policies will see increases, but elevation certificates showing lower risks could slow or prevent the increases, she said.

The new law requires increases of at least 5 percent a year for most subsidized premiums and allows up to 18 percent increases for most buildings.

The increases for some buildings, including non-residences and ones with severe or repetitive losses, were capped at 25 percent a year.

Baker said she doesn’t yet know how high the rates will increase each year for property owners. For a building with a $2,000 subsidized premium, the owner could see a rate of $20,000 a year in about 15 years if FEMA increased the rate 18 percent annually.

The only thing communities and building owners can do is try to mitigate the risks by taking steps such as flood-proofing the buildings, Baker said.

“In this day and age, you’ve got to mitigate the problem to change the rates,” she said.

REDUCED RISK

Nate Rudy, director of economic and community development for the city of Gardiner, said he’s looking to find out what type of federal grants are available for floodplain mitigation, especially in historic downtowns like Gardiner.

He said the immediate, acute need for the city is to ensure property sales aren’t falling apart because of flood insurance changes, but the city also needs to look for ways to lower the risk of flooding in its downtown buildings.

“I’m hoping that in the long term we will find the leadership we need to reassess the way this program is administered, so it doesn’t represent a grave threat to downtowns like Gardiner,” Rudy said.

The Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012 was passed to make the federal flood insurance program, which found itself deep in debt following payouts to property owners hit by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and earlier storms, more sustainable over the long term. It directed FEMA to phase out subsidies for older buildings and to change how the flood rate maps affected policy holders.

Most of the buildings receiving subsidies, which represents about 20 percent of total policies nationally, began seeing 25 percent premium increases at renewal.

Some owners trying to sell properties saw ten-fold increases in the premiums, causing outcry in flood-prone areas, especially along the coast.

The changes in March returned subsidized rates for older primary residences and businesses, according to a memo from FEMA, and allowed new policyholders purchasing eligible buildings to receive the subsidized rates starting May 1.

Madore, the insurance agent in Augusta, said he was surprised to see the quote for the downtown Gardiner building after May 1 actually drop lower than the subsidized rate from 2012.

Although he doesn’t think the rates will rise to the $20,000 to $30,000 range for similar downtown buildings, he said municipalities should partner with the building owners and the federal government when possible to find ways to floodproof the buildings.

“The cost to actually build structures or do what is needed, I don’t think the building owners could afford to pay it out of their pockets,” Madore said. “I think it really has to be the community and the building owners working collaboratively to revitalize their downtown.”

Building owners can dry and wet floodproof their structures to reduce their flood risks and lower insurance rates. Dry floodproofing is done by making a structure watertight to prevent a flood from entering, while wet floodproofing measures prevent or provide resistance to damage by allowing flood water to enter the structure.

NEW SLATES FLOODPROOFED

In downtown Hallowell, the developer who purchased the Slates restaurant building after a fire gutted it in 2007 had to dry floodproof the building because it’s in the floodplain.

Lon Walters, the developer from Waterville, said the efforts, which included constructing a rubber membrane around the building to make it watertight, didn’t provide any cost benefit, but it was required because the building was being substantially rebuilt in the floodplain.

Walters said he doesn’t remember how much that portion of the construction cost, but he wouldn’t have chosen to do it if it wasn’t required.

Peter Bethanis, the Readfield-based architect who did the work, said it would be impossible to estimate how much floodproofing may cost a building owner, but a building may not be worth as much as it costs to do all the work in some cases.

“Is it possible?” he said. “Anything’s possible if you have enough money.”

The potential cost is why Patrick Wright, director of Gardiner Main Street, said it’s important to pursue federal grants.

He said since the federal government recognizes the cultural importance of places and buildings on the National Register of Historic Places, such as downtown Gardiner, it should assist in protecting them with either preferential flood insurance treatment or funding.

“The situation still remains that flooding is a concern,” Wright said. “It always has been. It’s no surprise here. The best we can do is make our downtown buildings flood resistant to the very extent possible.”

Paul Koenig — 621-5663pkoenig@centralmaine.comTwitter: @paul_koenig

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.