A Scarborough man who was the first to negotiate several of the trickiest routes up Cathedral Ledge in New Hampshire’s White Mountains fell to his death while climbing there Saturday.

Brian Delaney, 56, was taking on the Barber Wall, a technically challenging sheer vertical face in Echo Lake-Cathedral Ledge State Park, when he fell almost 65 feet from the top, a state conservation official said Monday. Delaney landed on a ledge and suffered numerous broken bones and internal injuries.

His death shocked many in the rock-climbing community who knew him as someone who stayed in great physical shape and was always meticulous in his safety preparations. They, along with other friends and family members, also lamented the loss of an immensely likable and humble man.

“Every person who met him – from janitor to the CEO of the company he worked for – thought he was their friend, and he was,” said his wife, Dr. Kristine Hoyt, a veterinarian.

Delaney worked in information technology for Hannaford Supermarkets. He enjoyed fine music, especially singing with his 14-year-old daughter, Hana, and loved animals even more than his wife does, Hoyt said.

“He would take a spider and put it outside. He had huge respect for all living creatures,” Hoyt recalled Monday.

The two met when Delaney brought his cat in for Hoyt to examine. “This cat looked just like him – bright-red hair and a prominent nose,” she said. “You only had to look at him and his cat together and start laughing … and for the 23 years I knew him, he made me laugh.”

Delaney was extremely devoted to his sport, and was “probably the healthiest 56-year-old you ever met,” she said.

“He was in love with the rock first and me second,” Hoyt said. “My husband went out (rock climbing) every beautiful day he could, and it was a beautiful day on Saturday.”

The fall occurred about noon Saturday in Bartlett, New Hampshire, near North Conway.

Delaney had been climbing solo using ropes to secure him in case he fell. It appeared that he had reached the top of the climb and was preparing to rappel down when he fell, said Alex Lopashanski, conservation officer for the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department.

“Somewhere during the transition of moving to another route or attempting to descend, he fell back down from the top of that cliff,” Lopashanski said Monday. “He was either preparing to descend or re-rigging lines when he fell.”

Lopashanski said Delaney had been standing on a flat area where it wouldn’t be likely for someone to just fall off.

“Something happened – either while rigging or moving around – that caused him to go down. There was no malfunction. He was connected to it,” he said of the safety harness and ropes that Delaney had been using to secure himself.

“It didn’t arrest his fall based on the way it was connected,” Lopashanski said.

It’s not clear exactly what happened, he said.

“In the end, all we can really say for sure is something went wrong – either it was reconnected to the wrong piece of rope or he fell before he was ready to descend,” Lopashanski said.

Other climbers who were nearby responded, and members of the Mountain Rescue Service and North Conway Fire and Rescue were summoned. Lopashanski said it took him about 20 minutes to reach the ledge and another 20 minutes to get to the spot where Delaney landed.

One of those in the rescue party was Brad White, owner of International Mountain Climbing School, who had taken climbing classes with Delaney in the 1970s when they were both young men.

“He was as mild-mannered as you can get, totally mellow … just a really good guy to talk with, a real family-type person,” White recalled Monday.

Rescue workers loaded the injured climber onto a litter and, secured by their own safety ropes, began carrying him down from the ledge. On the way, Delaney stopped breathing and emergency medical workers couldn’t get a pulse. He died before they could reach the bottom.

White said it’s difficult to have been part of the team that tried to rescue his friend, but that also makes it easier to accept.

“If you hear about it afterward, you’re helpless. If you’re there and fighting and working hard to make things happen, at least you feel you gave it your best shot. We did everything we could,” he said.

Danger is an inherent part of the sport – something climbers take pains to manage – but is impossible to eliminate.

“If it wasn’t for danger, climbing wouldn’t exist,” White said.

Rock climbers work to demonstrate that they can overcome the physical and mental challenges posed by the climb and make it back safely, whether it’s a 400-foot climb or 20 feet.

“This is the kind of thing that gives a slap in the face,” White said of Saturday’s accident.

He said the fall was probably the result of some kind of error on Delaney’s part because the equipment was intact – but exactly what happened is a mystery.

Delaney was well-known in the climbing community and had been tackling the challenging routes in Cathedral Ledge for decades. The first ones to navigate a particular route up a face have the honor of naming it and are mentioned in the guidebooks. Delaney’s name appears several times, said Craig Taylor, a guide with White’s climbing school.

Delaney and Ed Webster, author of the guidebook “Rock Climbs in the White Mountains of New Hampshire,” climbed and named one of the routes up Cathedral Ledge “Women in Love” 40 or so years ago. It was one of the hardest technical climbs mapped at the time, although the ratings have grown progressively harder since, Taylor said.

“He was the best of the best during those times, climbing at a super high standard, some of the highest on the planet. He was really, really good and putting up really hard routes,” Taylor said.

Climbers try to unravel the mystery of a route – to figure out each of the moves needed to scale it.

“Sometimes hot climbers have a lot of hubris. He was the exact opposite,” said Taylor, who had met Delaney but knew him more by reputation. “He could do the easiest climb in the world and that was great.”

Four years ago, Steve Arsenault of Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, joined his longtime friend Delaney on a climbing trip to Moab, Utah.

“He’s an extremely humble guy – real low-key, off the radar. He never looked for fame but really was one of the most talented climbers around in New England back in the day,” Arsenault said. “If Brian devoted his life to climbing, he could have been one of the best in the country.”

Jimmi Dunn of Colorado Springs, former director of the EMS climbing school in North Conway, climbed with Delaney in New England and once cut a new route to the top of a 400-foot cliff in Utah.

“He was intense. I remember one time back in the early ’70s, he was doing about 70 pull-ups in a row,” Dunn said.

Delaney had kept himself in good climbing form.

“I understood he was climbing really well and in top-notch shape and very alert. I guess you’d have to say it was a freak accident,” Dunn said Monday, noting that rock climbing is a sport that does not tolerate such accidents. “When you have a freak accident in bowling, you drop the bowling ball on your toes.”

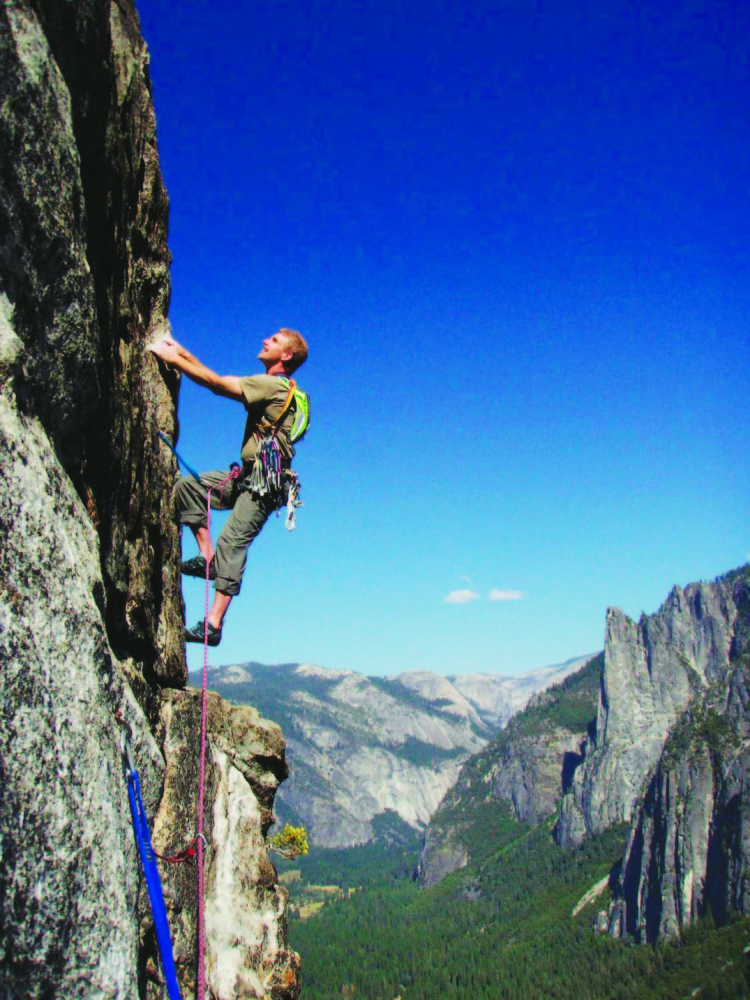

Last year, Delaney achieved what his wife described as his greatest physical accomplishment – an ascent up the face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park.

But, Hoyt added tearfully, it is not the legacy she values most.

“The thing I am the most proud of, of all my husband’s accomplishments in the whole world – and he has many – is that he was the best father anyone could ever be,” Hoyt said. “The thing he was most proud of in his entire life was his daughter.”

Hoyt said that in lieu of flowers and cards, donations can be made to Hana Delaney’s college fund made out to: USAA College Savings Plan, account number 500038446-0114, and mailed to USAA College Savings Plan, P.O. Box 55354, Boston, MA 02205.

David Hench can be contacted at 791-6327 or at:

Twitter: @Mainehenchman

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.