MADISON — The Weston family has owned their home on the banks of the Kennebec River since 1790, and moving out or selling it was never an option.

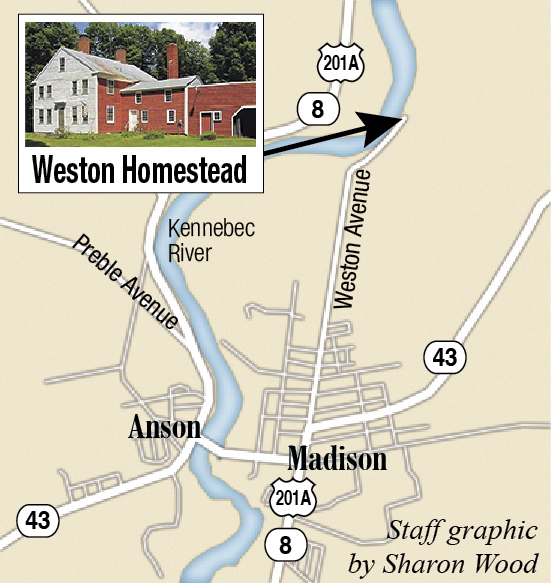

But times have changed, the family is scattered across the country and for the first time in its more than 200-year history, the home at 436 Weston Ave. and the more than 300 acres surrounding it may soon belong to someone else.

The Westons took good care of their property since Joseph Weston first moved to the plot of land from Massachusetts in 1771. Construction began on the house that’s there now in 1790. Over the years, the family added on — at one point moving a one-room schoolhouse and tacking it on to the dining room in the mid-1800s.

When hard financial times hit farms throughout the area in the 1890s, the Westons mortgaged most of the homestead farmland and livestock, but eventually got it back, with money from Addie Bixby Weston’s father.

The family lived there through World War II, and afterward, relatives would return to the house to ensure it was maintained.

When the flood of 1987 brought 57 inches of water from the Kennebec River pouring into the first floor of the two-story farmhouse, the Westons moved what furniture they could and restored what was damaged.

Through it all, the house stayed in the family.

Five years ago, the family decided to sell, but there was little interest in buying, let alone taking on the job of maintaining and preserving it.

The family has maintained the house, and it’s the site of an annual family reunion. It’s in good condition, with many furnishings that date back centuries. Though they listed it for sale, the family was worried about the property falling into the wrong hands — after decades of upkeep and work the last thing they wanted was to see the land subdivided and used for development.

But now, with the help of a real estate agent who saw something special in the house, a plan has evolved.

The family has connected with several historical preservation and conservation groups, and efforts are underway to preserve the entire 343-acre estate, including the woods and farmland.

In July the state Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry awarded a $112,500 grant toward creating a conservation easement on the property, a first step in securing the funding to preserve the estate.

“This is the best thing,” said Peter Weston, who lives in Scarborough and is one of 13 family members who share ownership of the estate. “It’s exactly what the family wants — to see the farm be preserved and appreciated.”

With the new plan the family has hatched, the estate will be divided into three parts each with its own caretaker — the home and barn with 8 acres; about 50 acres of farmland to be preserved through the Maine Farmland Trust; the remaining 282 acres of woods, which will become a conservation easement preserving the wildlife and ecological habitat and open to the public with the help of the Somerset Woods Trustees.

“It’s such a unique project,” said Nina Young, land protection and general manager for Maine Farmland Trust. “Every component is strong — a very well-stocked piece of woodland that has been sustainably managed, this historic house that is almost unchanged since it was built and contains all the family furniture and items in it. And this really gorgeous field that is the envy of farmers in a rich farming area.”

$5 AND AN OLD HORSE

Joseph Weston came to the area from Lancaster, Mass., in 1771, a few years before serving as a guide to Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War. He helped Arnold’s troops navigate the Skowhegan Falls in the Kennebec River on their way to the 1775 Battle of Quebec, and died of fever shortly after.

His son, Deacon Benjamin Weston, is said to have inherited the land from his stepfather, who bought it for $5 and an old horse in 1785, according to a family history compiled for a bicentennial celebration in 1986. The first deed, recorded in the county clerk’s office in 1793, lists the lot in Benjamin’s name.

The family believes he worked and lived there for at least a couple years before bringing his wife, Anna Powers, to the small cabin he had built in 1788.

The house — a two-story Federal-style clapboard frame — is believed to have been built between 1790 and 1800 and completed in 1817. In the meantime, Benjamin bought more land around the site, and the farm eventually grew to about 400 acres, including a large island in the Kennebec known as Weston Island, just north of the house.

Benjamin and Anna had 11 children, and they attached a one-room schoolhouse to make room for their family.

Their oldest son, Nathan, who along with his brother Benjamin founded a timber company, helped to fund the first railroad bridge over the river in Madison and contributed to the construction of the town’s first church building.

He eventually inherited the property and in turn sold it to his three sons in 1872, including Theodore, whose wife Addie Bixby was a correspondent for “Ladies Home Journal” in the late 1800s.

In addition to being dairy farmers and lumbermen, the Westons were strong advocates of education, and two of the six members of the first graduating class at the University of Maine were members of the family.

The farm mostly survived on money the family made in the timber business, but in 1927 they bought a dairy operation that they used to sell and deliver milk to homes and stores in Madison.

The dairy farm’s last year of operation was in 1945, when the last of the Weston boys to grow up on the property entered the Navy and the livestock and machinery sold.

Yet the house remained in the family, with someone living there through the 1980s, and has been the site of annual family reunions for years.

‘WE HAVE TO MOVE ON’

Teddy Weston, 93, of Winterport, remembers visiting the house for the first time in November 1938 with a Colby College classmate, a cousin of her future husband, Donald Weston, whom she met that weekend.

“It’s a magnificent place,” said Weston. “I remember the first time I went there. It was Thanksgiving time and in the middle of a snowstorm. I was so impressed with the age. Of course it has been modernized to some extent, but there are many things that have not been changed.”

During that cold November weekend, Weston said she was upstairs in the house and saw a Civil War uniform hanging on a hook in the hallway.

“I thought, ‘Holy Moses! What is that?'” she said. “I couldn’t believe it.”

The four sons of Wallace Weston, including Teddy’s husband Donald, have all died and no one from the family has lived in the house since 1986. A cousin, Nancy Drew, lives in a second house on the property that used to be a servant’s quarters.

Teddy Weston said that like her son, she supports the sale of the house.

“It’s come to a point where there is nobody living there and nobody in the family wants to live there. We have to move on,” she said. “If you leave the house idle for a very long time, that’s not good. I think this is the very best possible solution, that someone will value the house for the historical building it really is.”

After her husband died about five years ago, and the death of his surviving brother followed, the family decided to sell the house.

‘NOBODY HAS EVER MOVED OUT’

Donald Newell, a Unity real estate agent, said that when he first walked through the house with Peter Weston, he was amazed at the number of authentic and antique items still in it — the desks and chalkboard in the one-room schoolhouse; tools for making butter and peeling apples; boards for drying plants; and in the parlor the portraits of Ben Weston, his wife Almeda and their oldest son, Nathan.

“Until you go to a place where it’s all there you can’t describe the feeling,” he said. “Each room was like a tidal wave that just hit me with the stories it had to tell. I go into old houses all the time, but that one really took me back.”

It wasn’t just the house — which he said would be livable year-round with better insulation — that Newell said he was impressed with. He immediately recognized the value of the riverfront property, it’s woods and farmland, and encouraged the family to explore options that would preserve it — helping them to connect with Maine Farm Land Trust, Maine Preservation and the Somerset Woods Trustees, local and statewide organizations dedicated to land conservation and historic preservation.

He helped them to stage the house, or place all the items in the appropriate locations to lend a feeling of authenticity and as if the house had never been touched.

There are books laid out on the beds; children’s toys on the shelves in a playroom; dishes in the kitchen; spinning wheels and wood stoves; and stacks of newspapers and magazines in the attic. The Civil War uniform, though now in a glass box on a book shelf, is still in the upstairs hallway.

“It’s exceptional. I don’t know how this family happened to stay here, but they did it,” said Newell.

Preserving the house was not without challenges — perhaps the toughest among them and the one that most family members still remember is the April 1987 flood that brought 57 inches of water overflowing from the Kennebec River into the house. A marker on the wall about even with Peter Weston’s shoulder shows the water level.

The wallpaper from 1817 and 1836 is still in place and though most of the furniture had to be moved, it survived and has been placed back in the house.

“It retains all it’s original fireplaces, hearths, flooring and plaster work and all of the materials are still there,” said Greg Paxton, executive director of Maine Preservation. “It’s very significant because it’s one of the best preserved houses I’ve ever seen, if not the best, and I’ve been in the field for 40 years.”

Through a revolving loan fund, the organization helps find new owners for historic houses, using the fund to purchase a historic house and then making the money back on the sale of the house.

In 1977, the Weston Homestead was one of the first homes in Maine to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, according to Paxton, and is being listed for sale at $915,000.

“We are looking for a new owner who will be interested in the historic aspect of the building and maintain it well,” said Paxton. “It is what you might call a niche, but we have been getting a lot of response from around Maine and around the country to houses like this.”

A COMPREHENSIVE PLAN

Earlier this month Land for Maine’s Future, a project of the state Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, announced a $112,500 grant to create a conservation easement of the working forest — the first part of what those involved hope will be a comprehensive plan to preserve the estate.

The forest, originally harvested for the family’s own use, will now continue to be managed as forestland and will also be open to the public with an expansion of recreational uses, including hiking and fishing, all-terrain vehicle and snowmobiling, fiddlehead gathering and cross-country skiing.

The town of Madison, which has been involved in preliminary discussions with the nonprofit organizations involved, would love to see the estate preserved and be able to provide public access to the riverfront property, said Town Manager Dana Berry.

“Letting the public have the opportunity to enjoy the resources I think would be advantageous to the long-term growth of the area,” said Berry. “We certainly would like to see it preserved. It’s a local treasure basically.”

About 50 acres of farmland, coveted for its proximity to the river and a type of soil known as hadley silt loam, will also be preserved through the Maine Farmland Trust, a statewide organization that works to protect and preserve farmland.

The field is covered in tall stalks of corn about 10 feet high that belong to a local farmer who rents the property. Because of the many organizations involved in conservation efforts and the complicated process of securing funding, it will take time for the Westons to realize their vision for the property.

“There are a lot of pieces that still have to come together,” said Young. “It’s a very special place, and that’s why we’re all gunning to protect it, because it’s just so unique to Maine.”

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.