Late one night, Deputy Joseph Jackson got a call at home from an officer who had just arrested a driver for swerving all over the road.

The officer called Jackson, a Somerset County sheriff’s deputy, because he is a trained drug recognition expert. The driver had silver paint on his face that could indicate he’d been “huffing,” or inhaling paint fumes, and had failed field sobriety tests.

Under standard protocol, the officer took the driver to the jail, where the driver tested negative for alcohol.

If alcohol is abused, an officer can build a case for operating under the influence. To build a case based on drug intoxication, police must call one of 80 drug recognition experts in the state who can weed out which combination of drugs might be in a driver’s system.

In the case of the Somerset County driver, the officer told Jackson that by the time the driver was taken to jail and the officer called Jackson, he already seemed less impaired than he was when initially pulled over.

“The officer is already telling me that this guy is starting to come around,” Jackson said. “I tell him, I could run up and come look at him for you. Depending on what type of chemical was in the paint, I still might be able to see some of the medical things. But most likely there would be nothing to see.”

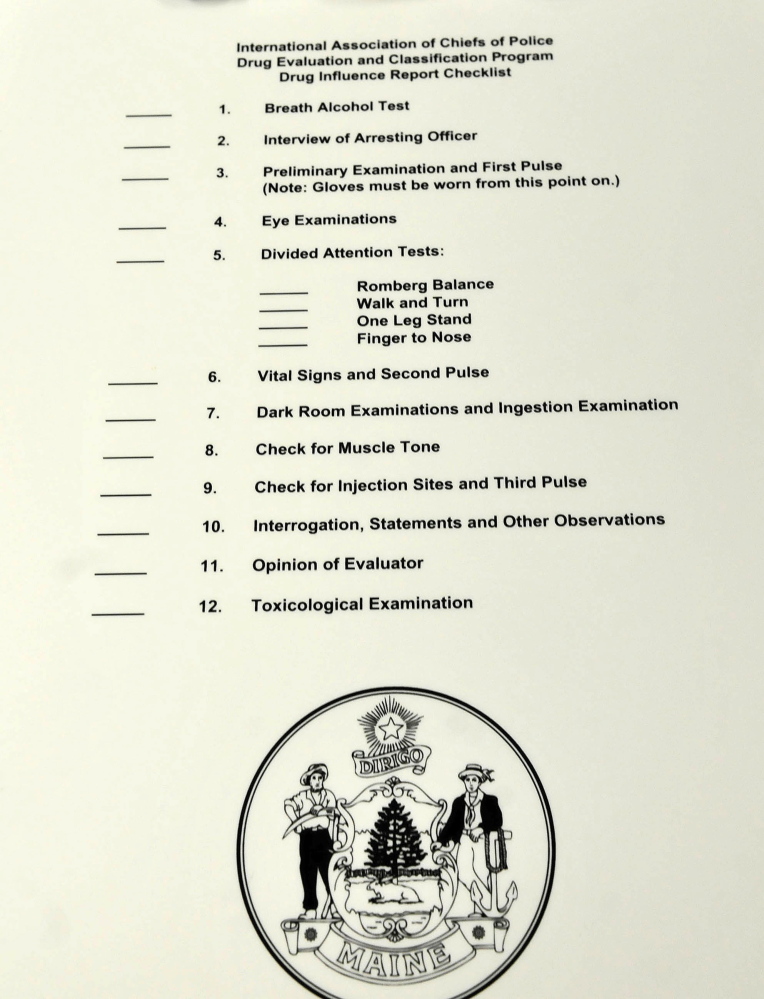

Even after he explained how the effects of inhalants probably would wear off by the time he arrived and conducted the 12-step drug detection procedure, officers still waited for Jackson to come.

Others in similar circumstances, though, would call the case a loss and either turn it over to the district attorney or drop charges against the driver, who is then free to leave.

Long distances, the short-lived effects of drugs and only a few trained experts to work large patrol areas are some of the challenges facing drug recognition experts trying to charge driving under the influence of drug cases, and these challenges are aggravated in rural areas of Maine such as Somerset County, where Jackson works.

The issue is compounded by the fact that the training to recognize the hundreds of ways drugs and drug combinations can present themselves is considered one of the hardest courses taught at the Maine Criminal Justice Academy. The next course starts in January, and applications are being taken now; but officials with the program say recruits are hard to come by and not all applications are accepted.

The academy is still interviewing candidates for the upcoming course in January. Jim Lyman, training coordinator for the Maine Criminal Justice Academy, said he is pleased that out of the five candidates who applied so far, two are from Hancock County.

He said that’s “exciting because Hancock and Washington are hard to get candidates from because the agencies are so spread out.”

SMALL DEPARTMENTS AT A LOSS

In 2013, drug recognition experts in Maine submitted 264 urine samples for testing with the Department of Health and Human Services testing laboratory, the final step police take to build a drug OUI case. There were more than 8,000 arrests on the charge of driving under the influence in 2013 in Maine, according to the Secretary of State’s Office.

While the cost of training an expert is picked up by the Maine Bureau of Highway Safety, having a drug recognition expert on staff is still hard on some of the smaller, more rural departments.

Lyman said having an officer trained as a drug recognition expert can be too much to ask of a small rural department that can’t always spare one of its four or five officers to go on a three- or four-hour call for the county.

The Franklin County Sheriff’s Department has no drug recognition experts on its staff, Sheriff Scott Nichols said. Nichols said all police training requires upkeep and recertification, and deputies in the small department already are maintaining other specialties that assist other departments.

“We have three K-9 units, which keep us pretty busy. We’ve got a guy now that’s gone training to learn accident reconstruction,” he said.

There are two police officers in Franklin County and three in Somerset County who are always on call as drug recognition experts, in combination with a drug recognition expert from Maine State Police Troop C that assists both areas.

The Franklin County Sheriff’s Department, Wilton, Rangeley, Carrabassett Valley, Madison, Pittsfield, Skowhegan and Fairfield don’t have drug recognition experts, so they rely on experts from the Somerset County department.

DRUG EVALUATION

In Franklin County, Sgt. Edward Hastings, of the Farmington Police Department, also on call as the Chesterville fire chief, said if he’s not working, it can take 30 or 40 minutes for him to arrive at the jail when he is called in as a drug recognition expert.

When evaluating a person, he said he looks at both medical and physical signs that the driver might be displaying.

He takes blood pressure, temperature and pulse to see if any vital signs are elevated or lowered. He holds up a chart of different-sized semicircles next to the driver’s eyes to see what size they are and whether they react to light changes.

He asks about current drug use and observes body language and muscle tone. All experts have a form that includes a picture of an arm where experts can document track marks. In one example, Jackson said he noted 1 inch of collapsed blood vessel in a woman’s arm, which indicated about 250 previous injections to the same site.

There is a chart with pictures of triangles where the Hastings makes a dot to show where the driver’s finger landed when asked to touch his or her nose.

By the time the officer rules out alcohol, gets the suspected driver to the jail and calls for a drug recognition expert, some substances may be out of the driver’s system, Hastings said. Others can impair a driver for the night.

Measurable signs of cocaine use can be gone in 90 minutes. Inhalants leave the system even faster. Marijuana can impair a person for hours. Methadone can impair a person all day.

Hastings said the odds of a drug recognition expert arriving in time to build a case for driving solely under the influence of inhalants are “slim to none.”

“We’ll catch them next time,” he said.

He said in order to maintain the 12-step process’s integrity as evidence in court, there is no way to speed the process or cruise through steps.

“I don’t know of a simple solution to make it better,” he said. “I want to make sure I’m looking at everything. I wouldn’t want someone to shortchange me just because I was driving around tired.”

Jackson said to stay up to date on the changing topic, he studies drug recognition even in his free time. He watches documentaries on drug culture on his days off or finds new books on drug use to read.

He said this year he primarily has responded to people abusing prescription drugs, which are typically long-lasting and display measurable symptoms, when he is called to evaluate the driver.

Since Jackson became a drug recognition expert in 2005, he said, the kinds of drugs he primarily responds to have come and gone in phases.

“One year, ecstasy and marijuana were the thing I always saw,” he said. “It comes and goes.”

NEXT STEPS

The drug recognition program was started in the early 1970s by Los Angeles police officers who wanted a way to prove the influence of drugs in more than just the most obvious cases. In the 1980s, the standardized LAPD procedure caught national attention and became a formal national program. By the early 1990s, all 50 states were participating in the program.

In Maine, there are about 80 drug recognition experts, but most of the experts are concentrated in the southern part of the state, according to Lyman, of the Maine Criminal Justice Academy.

Lyman, who coordinates the drug recognition expert program, said there were as many as 120 drug recognition experts at one point, but the program is intensive and many officers are unable to maintain their certification.

“It’s one of our more difficult programs we offer. It’s a difficult course academically. There are a lot of different combinations of drugs and prescription drugs, and it’s quite an intensive program to learn to know and recognize them,” he said.

Admission to the program involves an interview at the academy. Lyman expects about 15 candidates to be admitted out of 30 to 40 applicants for the next course.

Lyman said the academy has struggled to keep drug recognition experts available in rural areas. They have a hard time keeping experts trained and available in Washington County. He said Aroostook, Somerset and Franklin counties have some experts but could use a few more.

“North of Augusta and of the populated area, it is a concern,” he said.

One of the last steps in initially training as an expert is to go to Portland or Bangor to find street volunteers with whom they can practice recognizing drug use.

Jackson said instructors will find users, often people police recognize by name, who will volunteer in exchange for some pizza to let the training officers practice detecting what is in their system.

“I’ll interview them first and tell them they can lie,” said Jackson. “After all, I mean, that’s work. People aren’t always going to tell you the truth.”

Getting down to Bangor or Portland, however, can be a long way for some police. Mileage expenses alone might be more than a small department is willing to shell out.

Jackson said there were some trainees in the rural area who were having a hard time getting to one of the two cities in time to complete their certification.

To try to address this, in an experiment, Jackson said he recently scheduled a training session in Dexter to see if enough people in the town of 3,800 could be found to practice on. While the town is convenient, he was concerned that it would be too small to find enough drugged volunteers.

“But we found plenty,” he said.

Kaitlin Schroeder — 861-9252

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.