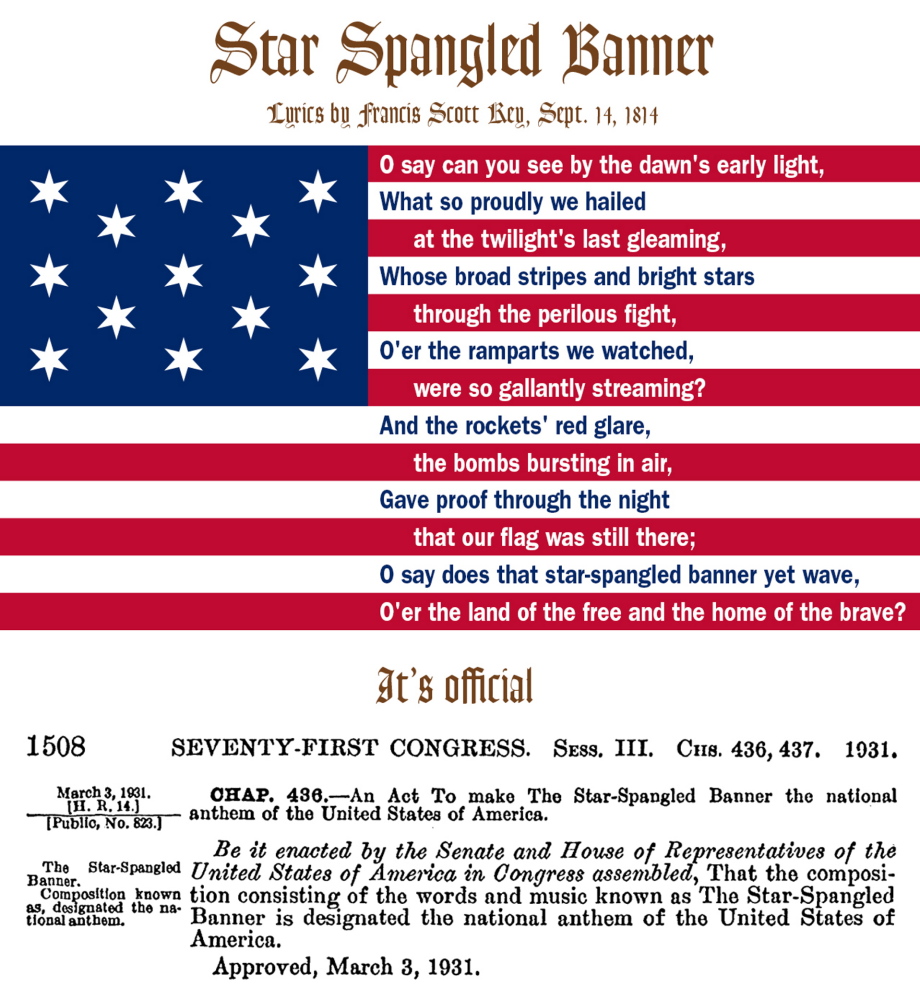

Sept. 14 marked the 200th anniversary of the writing of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Over the years, many debates have surrounded the national anthem — involving its meaning, its quality and the circumstances under which Francis Scott Key came to write it. Before you hear “Oh say, can you see … ” at the next ballgame or school assembly, make sure you’ve dispelled these myths first.

1. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was written about an insignificant battle in an insignificant war.

The nation’s future was at stake in 1814, with the United States on the brink of defeat in the third year of the War of 1812, a conflict with Britain that would determine the future of the North American continent. The battle for Baltimore took place three weeks after the British captured Washington, leaving the Capitol, the White House and virtually every other federal building a smoking ruin.

With President James Madison’s government on the run, the U.S. treasury bankrupt and British forces preparing an attack from Canada to sever New England from the rest of the country, there was widespread fear that another defeat could force the collapse of the government and the dissolution of the Union.

Yet the United States escaped disaster largely because the repulse of the British at Baltimore and the concurrent U.S. victory at Lake Champlain forced Britain to drop harsh peace terms. For many Americans, this second war of independence created a feeling of national unity that had not truly existed — a fitting moment for the nation’s anthem to emerge.

2. The anthem is a celebration of war.

The song’s lyrics are “mindless nonsense about rockets and bombs” and “empty bravado,” columnist Michael Kinsley wrote in 2009. Actually, “The Star-Spangled Banner” is more a hymn of thanks by the devout Key, who feared that Baltimore would be destroyed.

The 35-year-old Georgetown lawyer, attempting to gain the release of an American prisoner, had been detained by the British as they prepared to attack Baltimore. Beginning on the morning of Sept.13 and continuing for 25 hours, Key watched the British fire up to 1,800 bombs and 800 rockets in an attempt to destroy Fort McHenry and reach the city.

Rather than martial chest-thumping, Key’s first verse is a long question, wondering not just whether the flag still flew over the fort but also whether the young nation would survive. In the dark hours before dawn, the guns fell quiet. For Key, the silence was dreadful, a sign that the fort may have fallen. The second verse captures Key’s relief at spotting the American flag “in full glory reflected” at first light.

The rarely sung third verse is angry and vengeful, rejoicing that the enemy’s “blood has washed out their foul footstep’s pollution.” Perhaps the lyrics reflect Key’s emotion after watching the British attempt to incinerate Baltimore. Key takes a more pious tone in the fourth and final verse, celebrating the return of peace and the end of “war’s desolation.”

The man who wrote this most patriotic of American songs in fact deeply opposed the war. Key had been dismayed by the U.S. declaration of war in 1812, considering it foolhardy for the young nation to take on one of the most powerful militaries on Earth.

3. Key was too far from Fort McHenry to see anything, let alone the flag.

British Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, directing the attack, wanted Key close at hand to help negotiate the expected American surrender. “Previous to the attack he asked Mr. Key … whether there was any person in the fort authorized to surrender,” wrote an American soldier at the fort who spoke to Key’s party after the attack.

Many accounts erroneously say Key was on a British ship, anchored far away from the bombardment. But before the attack, Key and the other Americans accompanying him were allowed to reboard their own sloop, guarded by a detachment of Royal Marines. A sketch by a Maryland militia officer watching the bombardment shows an American sloop anchored with the British bombardment squadron, a location where Key would have had an unparalleled view.

4. We should make “America the Beautiful” our anthem.

Whenever a performer botches “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the Super Bowl, the song gets blamed. “America the Beautiful” is usually proposed as a lovely and more easily rendered alternative (though petitioners to WhiteHouse.gov have also suggested R. Kelly’s “Ignition”).

Those who dislike the song should consider what it meant to the troops who fought to save the Union during the Civil War. Until then, “The Star-Spangled Banner” was one of several informal national anthems, ranking behind “Hail Columbia” and “Yankee Doodle.” But Key’s song resonated when the American flag came under attack at Fort Sumter. It was embraced by federal troops, who played it as they entered Savannah, Richmond and New Orleans. In the years that followed, the Army and the Navy gave it more formal status as the national anthem.

Even so, efforts to win congressional designation faced decades of opposition, including from prohibitionists and some religious figures. American Christian Science leader Augusta Stetson took out newspaper ads calling the song “a barroom ballad composed by a foreigner.” The drinking-song label, while true, is misleading. The original tune, “To Anacreon in Heaven,” was written around 1775 by English composer John Stafford Smith and paired with lighthearted lyrics to be sung by members of a London gentleman’s club after dinner. As for the tune’s English origins, anthem scholar Oscar Sonneck said in 1914: “We took the air and we kept it. Transplanted on American soil, it thrived.”

Ever since the legislation passed in 1931, critics have demanded a new anthem. Caldwell Titcomb, writing in the New Republic in 1985, complained that the anthem is too difficult to sing and “of low quality as poetry.” Yet the great American composer and U.S. Marine Band director John Philip Sousa felt differently, calling it a “soul-stirring song” and “a very satisfactory anthem.”

Before the 1931 designation, Sousa was encouraged to enter a contest to establish a national anthem. He was not sorry to lose, nor surprised that the winning song was forgotten. “Nations will seldom obtain good national anthems by offering prizes for them,” Sousa later said. “The man and the occasion must meet.”

Two hundred years ago, at a fateful moment in American history, they met.

5. The flag flying over Fort McHenry during the bombardment is on display at the Smithsonian.

The iconic garrison flag at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington was sewn by Baltimore flagmaker Mary Pickersgill and helpers, including her 13-year-old daughter, Caroline, and a young African-American indentured servant, Grace Wisher. The 42-by-30-foot wool flag flew before and after the British battle, but the best evidence indicates that a smaller storm flag — also sewn by Pickersgill — was flying during the attack. The storm flag, smaller but respectably sized at 17-by-25-feet, has long since disappeared.

A fierce storm was raging during much of the bombardment, and the wet garrison flag would have been so heavy that it would probably have snapped the flagpole. Analysis by Smithsonian conservators has shown no evidence that holes in the flag at the museum were a result of battle damage. But the bigger flag still deserves its revered status. It was raised over Fort McHenry after the bombardment ended on the morning of Sept. 14, 1814, a sight that galled the British but thrilled Francis Scott Key and every other American who saw it.

Steve Vogel, a former Washington Post reporter, is the author of “Through the Perilous Fight: From the Burning of Washington to the Star-Spangled Banner: The Six Weeks That Saved the Nation.” This column was distributed by The Washington Post, where it first appeared.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.