The legal wrangling about Canada lynx in Maine may not be over despite federal officials’ decision last week granting the state a permit allowing “incidental” trapping of the protected cats.

Wildlife advocates are considering whether to file suit in hopes of overturning a permit that allows most trapping to continue in Canada lynx territory in Maine by shielding the state from liability under the Endangered Species Act when lynx turn up in legally set traps. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service granted the “incidental take permit” to Maine 12 years after negotiations began with the state and after several lawsuits targeting Maine’s trapping rules.

Mollie Matteson, senior scientist for the Center for Biological Diversity, said her organization will be reviewing the administrative record to decide whether to challenge the plan in U.S. District Court. But Matteson said the group is “definitely not happy” with a plan that her organization and the Wildlife Alliance of Maine insist relies too heavily on trappers to self-report captured lynx.

“It’s really unfortunate that despite the years of work that have gone into this and the evidence that lynx are still being caught … that the Fish and Wildlife Service finally buckled and issued the permit,” said Matteson, whose Vermont-based group is involved in multiple endangered-species lawsuits against federal agencies. “I do not believe that is healthy for the lynx over the long term.”

State and federal wildlife officials as well as trappers praised the decision.

“We are glad we got it,” Brian Cogill, president of the Maine Trappers Association, said Monday in between tending his trap lines. “We have been waiting a long time for this to happen.”

Maine is home to the East Coast’s only sizable breeding population of Canada lynx, a “threatened” species that is rarely seen but has become a flashpoint in the state between trappers and animal rights groups. Weighing up to 30 pounds, lynx are similar in size to common bobcats but have large, padded feet that function like furry snowshoes as they pursue hares and other prey in the deep snow of northern Maine.

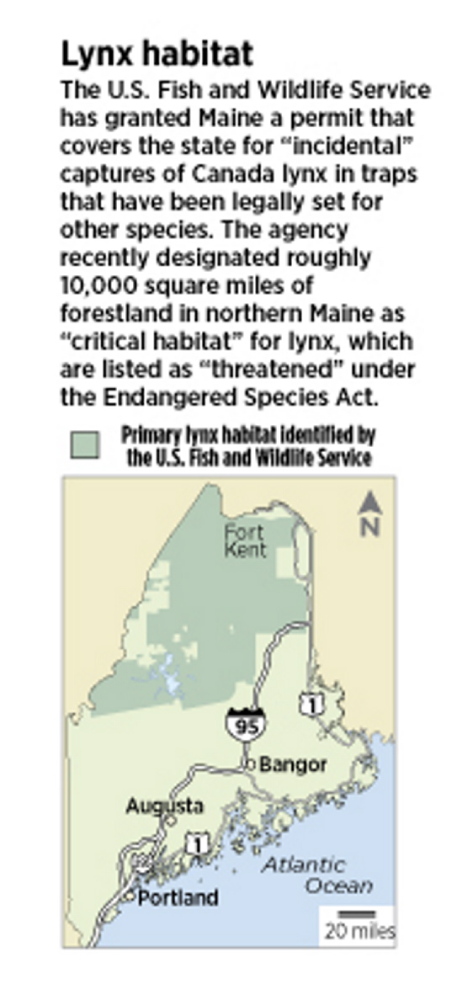

The state is home to more than 500 lynx living primarily in the commercial forests of Somerset, Piscataquis, Aroostook and northern Penobscot counties. Roughly 10,000 square miles of Northern Maine has been designated as lynx “critical habitat” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, thereby requiring another layer of federal review for any projects or development that could affect lynx.

Although reclusive creatures, dozens of lynx have turned up in traps set for other species during the past decade. Most of the animals are released unharmed or with only superficial injuries, according to biologists. But more than a half-dozen lynx died or were killed in traps between 1999 and 2013. And because lynx are protected from harm or harassment under federal law, the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife has been under heavy pressure for more than a decade to reduce the number of lynx caught in traps.

The “incidental take permit” issued last week by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service allows up to 195 lynx to be captured over the next 15 years in traps set for pine marten, fisher, coyotes and other species. The permit specifies that 183 of the 195 lynx must be released unharmed or with minor injuries, and no more than nine should be injured to the point of requiring rehabilitation prior to re-release. The permit allows up to three lynx deaths from traps.

Trappers now are required to wait for biologists or game wardens to inspect trapped lynx before releasing the animals. Thirteen of the 14 lynx reported caught in traps in Maine last year were released immediately, while one was released after undergoing rehabilitation for an injury. That lynx was fitted with a radio collar and is still alive, DIF&W officials said Monday.

Meagan Racey, spokeswoman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s regional office in Massachusetts, credited Maine DIF&W for taking “very notable” steps in recent years to reduce the likelihood of accidental lynx trappings. Those steps include prohibiting the use of lethal body-gripper traps except with special precautions, banning the use of uncovered bait and requiring sportsmen to set traps in ways that would be difficult for lynx to access.

Racey said the permit could now serve a model for the handful of Western or Midwestern states with lynx populations, Racey said.

“This was a particularly complex conservation planning process,” Racey said. “We certainly wanted it to result in the implementation of a plan that would successfully minimize the impact on Canada lynx yet would allow Maine trappers to continue trapping and would support our efforts to restore the species. I think what this plan really does illustrate is that the Endangered Species Act has built-in flexibility for activities when applicants can demonstrate that they have taken steps to minimize impacts.”

Matteson and Daryl DeJoy with the Wildlife Alliance of Maine argued the federal plan does not go far enough and actually weakens court-ordered protection stemming from Wildlife Alliance of Maine lawsuits against the state. DeJoy called it “self-delusion” to think that trappers will self-report all of the lynx caught in traps, especially those killed by so-called Conibear or body-gripping traps.

“I don’t think we will ever see another lynx caught in a Conibear trap unless a warden finds it … because they won’t be reported,” DeJoy said.

As part of the permit, the state of Maine has agreed to maintain actively at least 6,000 acres of lynx habitat at any given time within the Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands’ Seboomook Unit north of Moosehead Lake. That land will be located within a roughly 22,000-acre portion of the unit where forestry practices will be used to create the type of habitat needed for snowshoe hare, the lynx’s primary prey.

“Working together, we have reached an agreement that continues to safeguard Maine’s lynx population, while allowing the State of Maine to move forward with our wildlife management programs,” James Connolly, director of the Maine DIF&W Bureau of Resource Management, said in a statement. “This plan is an excellent example of how agencies can work together to achieve shared goals.”

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.