The march of time can be cruel. As months and years go by, it erodes even the most horrifying events until they are dulled of their searing poignancy.

Even one of the worst industrial disasters of our time fades from the world’s consciousness after decades have gone by. Thirty years ago, on the night of Dec. 2, 1984, the city of Bhopal, India, was forever identified with catastrophic tragedy. A toxic gas leak from a Union Carbide India Ltd. (UCIL) plant in the center of the city claimed the lives of thousands of people virtually overnight. Half a million people were exposed to contaminated water and air. The news and images of thousands of men, women, children and babies left dead on the ground, having tried to escape the gas, shocked the world.

Three decades later, the attention has gone. But the effects of that horrific day — and the lack of accountability — remain. Upwards of 22,000 people have died as a result of the leak, but the people of Bhopal continue to suffer from health problems, and the land and water are still contaminated.

The ruins of the plant still stand and are still poisoning the city. But no one will accept responsibility for the cleanup. Seven former employees of the Indian subsidiary of Union Carbide were found guilty of death by negligence, but U.S.-based Union Carbide Corporation (UCC) — a majority owner of the UCIL plant — itself refused to respond to criminal charges, and has been declared an “absconder from justice” by a court in India. Dow Chemical acquired Union Carbide in 2001, but has refused to ensure that Union Carbide responds to multiple judicial summons from Bhopal courts to answer for the disaster.

Bhopal was no mere accident. It was the result of a series of avoidable consequences because of cutting corners, exploiting an untrained and desperately poor workforce, and ignoring all warning signs that could have avoided calamity. And someone must answer.

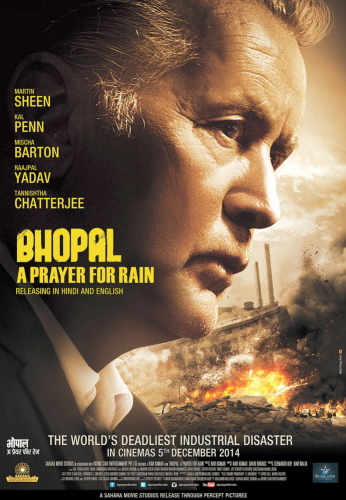

It was this outrage at the lack of justice that prompted me to make the film “Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain,” which was released in the U.S. last month. The scars of that terrible day remain. There are those who still walk the narrow streets with canes after the toxic gas devastated their eyes. Children continue to be born with birth defects, something local activists attribute to the effects of drinking water contaminated by chemicals left at the site. The site of the plant itself is rusting and overgrown, but still seeping poison.

When we visited Bhopal for filming, we attempted to get some footage at the ruined site. Workers’ helmets still sat on tables where they were left. Weathered safety signs are still affixed to the walls as silent ironic witnesses. And the smell of cyanide still remains. Our crews could not stay long because of it.

Dow’s stubborn refusal to admit any kind of responsibility for Union Carbide over this matter is baffling. Though Dow Chemical was not responsible for the leak itself, it is now 100 percent owner of Union Carbide and must therefore answer for its obligations. From a public relations perspective, significant goodwill could be won by investing in the cleanup and in the health and education infrastructure of Bhopal.

Instead, Dow has used the promise of significant future investment in order to lure the support of the Indian government for its demand to stop all legal action against the company in India. Its Indian subsidiary has sued peaceful demonstrators and taken out restraining orders against protests.

These are not the actions of a responsible corporation. We will keep telling the stories of the victims and survivors and keep working with organizations like Amnesty International, which is currently encouraging members to support survivors by writing to DOW as part of its annual “Write for Rights” campaign, until Dow and Union Carbide step up and finally give the people of Bhopal the resolution and renewal they deserve.

We must not allow the march of time to dull the urgency. Bhopal was not merely a tragedy of the 20th century. It is a human rights travesty today.

Ravi Kumar is a director whose film, “Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain,” was released in the U.S. last month. He wrote this in partnership with Amnesty International USA. This essay was distributed by Tribune Content Agency LLC.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.