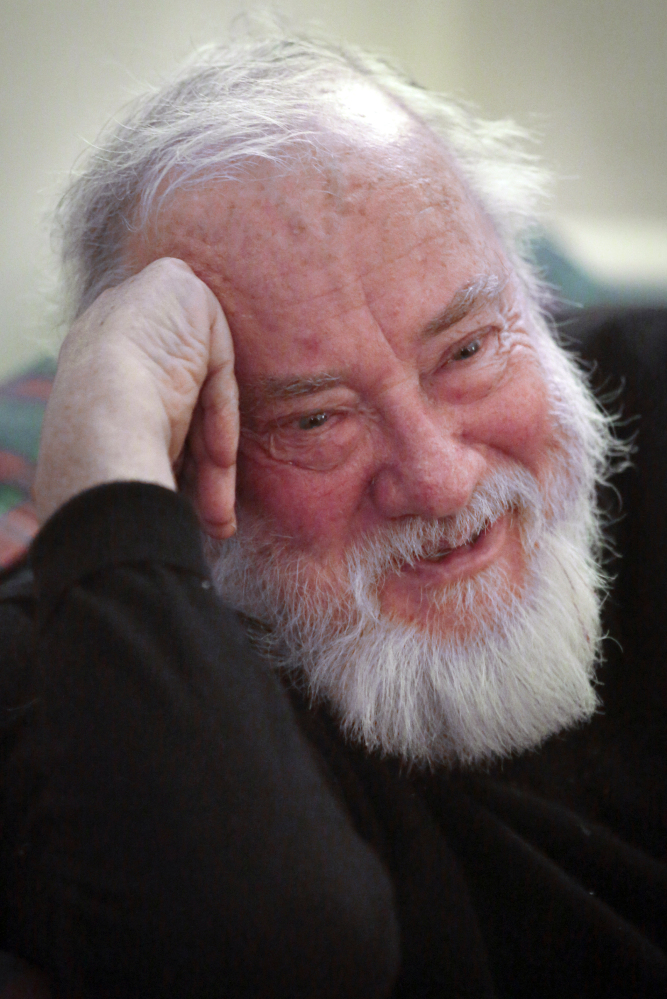

Robert Stone, who was regarded as one of the foremost American novelists to emerge from the tumult of the Vietnam War and the counterculture, an era whose agonies and legacies he captured in bracing narratives, died Jan. 10 at his home in Key West, Fla. He was 77.

The cause was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, said his wife, Janice Stone.

Stone was widely regarded as one of the most significant novelists of his generation. He often was compared to Joseph Conrad, with whom he shared a dark awareness of moral fragility, and to Ernest Hemingway, another chronicler of people adrift in an unforgiving world. (Also like Hemingway, Stone sported a distinctive beard.)

His novels – among them “Dog Soldiers,” the winner of the 1975 National Book Award for fiction – were the products of a lifetime of geographic and intellectual wandering. Stone spent periods in the Navy, as a foreign correspondent in Vietnam and with Ken Kesey, the author and countercultural figure whose psychedelic travels were recounted by Tom Wolfe in “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” (1968).

In his novels, Stone took readers into the underworlds of drugs, violence and strife, both cultural and personal. His characters were sometimes strung out, often morally ambiguous and, above all, real.

His first novel, “A Hall of Mirrors” (1967), was set in the maelstrom of New Orleans, where Stone had lived for a time, writing and performing his poetry and taking stock – literally – of its inhabitants as a census worker in 1960. Its central characters included a dissolute right-wing radio broadcaster and other misfits who head inexorably toward ruin.

“The American Way is innocence,” the broadcaster declares in a pivotal moment in the book. “In all situations we must and shall display an innocence so vast and awesome that the entire world will be reduced by it. American innocence shall rise in mighty clouds of vapor to the scent of heaven and confound the nations!”

The writer Ivan Gold, reviewing the book in The New York Times, described Stone’s language as “rich yet unobtrusive, self-effacing but in complete control.”

After his debut novel, Stone reported briefly in Vietnam for a British publication. That experience, along with his observations of cultural turmoil at home, resulted in “Dog Soldiers” (1974).

The book featured a journalist who conspires with a former Marine to smuggle heroin from Vietnam to the United States. Eventually they are intercepted by corrupt federal agents. It was noted that Stone had created a fictional world not unlike the real one, where the good characters seemed indistinguishable from the bad.

Stone continued writing until very nearly the end of his life. “A Flag for Sunrise” (1981), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, implicitly critiqued U.S. involvement in Central America. It was set in a fictional country called Tecan that resembled strife-torn Nicaragua.

“Children of Light” (1986), an unfavorable portrait of Hollywood based on his working experiences there, was less critically acclaimed than his previous books. “Outerbridge Reach” (1992), delved into the soul of a sailor during a solo trip around the world.

Later volumes included “Damascus Gate” (1998), a thriller set in Jerusalem and populated with religious fanatics, and “Bay of Souls” (2003), about a malcontent professor and his dangerous entanglement with a woman.

Stone’s final novel, published in 2013, was “Death of the Black-Haired Girl,” a psychological thriller that derived its drama not from violence in far-flung international engagements, but from an affair and a mysterious death in a small New England community.

“I believe that in fiction,” Stone once told the Times, “character is literally fate.”

Robert Anthony Stone was born Aug. 21, 1937, in Brooklyn. He was an infant when his father left him and his mother, who had schizophrenia.

He spent part of his childhood in an orphanage and quit high school, having fought with the Marist brothers at the Catholic school he attended. He retained, however, what he described as an intensely spiritual inner life.

“I discovered that my way of seeing the world was always going to be religious – not intellectual or political – viewing everything as a mystic process,” he once told The Washington Post.

In the mid-1950s he traveled around the world, including to Antarctica, while serving in the Navy. He left New York University to work at the New York Daily News, and later held a Stegner fellowship in creative writing at Stanford University. In California he met Kesey, author of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

“Bob despairs, and there’s something noble about the way he does it,” Ken Kesey told The New York Times in 1992. “Bob used to get high, stand naked in broken glass and stare at the sky and shout. . . . He’s a warrior, and not just as a writer. With his whole life he’s battling Moloch.”

In addition to his novels, Stone wrote short story collections including “Bear and His Daughter” (1997), which was a Pulitzer finalist, and the memoir “Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties” (2007). He wrote the screenplays of the films “WUSA” (1970), an adaptation of “A Hall of Mirrors” starring Paul Newman, and “Who’ll Stop the Rain” (1978), based on “Dog Soldiers” and featuring Nick Nolte.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.