NORRIDGEWOCK — The last time racehorse Postcard Jack was on the track at the Skowhegan State Fairgrounds was in August 2010 during a memorial for the horse’s namesake.

“Postcard Jack” was the mystery man who for more than three decades sent thousands of anonymous postcards from all over the world to a restaurant in Madison. Jack turned out to be Jack Garbarino, who was 67 when he died in December 2009 in New York City.

On that day at the fair in 2010, Postcard Jack — the winningest standardbred horse in state history — was harnessed up in full racing gear and paced around the track in a memorial lap for Garbarino.

“He knew where he was and what he was supposed to do,” said Debbie Hight, whose family has owned the horse for many years. “He was calm in the paddock. Then he was out on the racetrack and — zoom — away he went.”

The original Postcard Jack, a management consultant with ITT, Dun & Bradstreet and McKinsey & Co., sent an estimated 8,000-9,000 postcards from all over the world to the Oasis Restaurant in Madison beginning in 1979 — sometimes posting 100 cards in a single month.

He grew up in The Bronx, N.Y., and attended Fordham University under the ROTC program. Jack received his law degree from Yale University, served in the U.S. Army and later graduated from Harvard Business School, according to his obituary.

Although he visited the restaurant, later called River’s Edge and now closed, several times over the years, he never revealed his identity.

The mystery of Postcard Jack remained just that — a mystery — for more than 30 years.

Walter Hight, of Skowhegan, Debbie Hight’s brother-in-law, said he and his business partner, Tom Dillon of Anson, bought a harness racehorse in 1990 and decided to name it Postcard Jack during dinner one night at the Oasis, where many of the postcards were on display.

Now the four-legged Postcard Jack, who turned 25 in March, is being trained to slow down, take new commands and go from a career as a competitive racehorse to a saddle horse.

And it’s not easy, Debbie Hight said.

“We’re trying to make the horse safe to ride for anyone,” she said. “It’s such a great thing to rescue any animal, but they’re dangerous — he was dangerous. He could kill you. That’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to teach horses so that people can rescue them.”

Jack is 15.1 hands tall, or about 5 feet, 2 inches, from the withers, and weighs about 1,000 pounds.

Postcard Jack retired at age 14 in 2004 as the top horse in Maine history with the most finishes of less than two minutes and the most wins at 77 in 324 starts. He was a pacer, not a trotter.

A pacer is a racehorse whose front legs and back legs move at the same time — right front, right back, left front, left back, Hight said. A trotter’s moves are different with the opposite front leg and rear leg hitting the ground at the same time.

Pacers are faster than trotters, she said.

“We don’t want him to pace because it’s impossible to ride,” Hight said. “This is difficult work.”

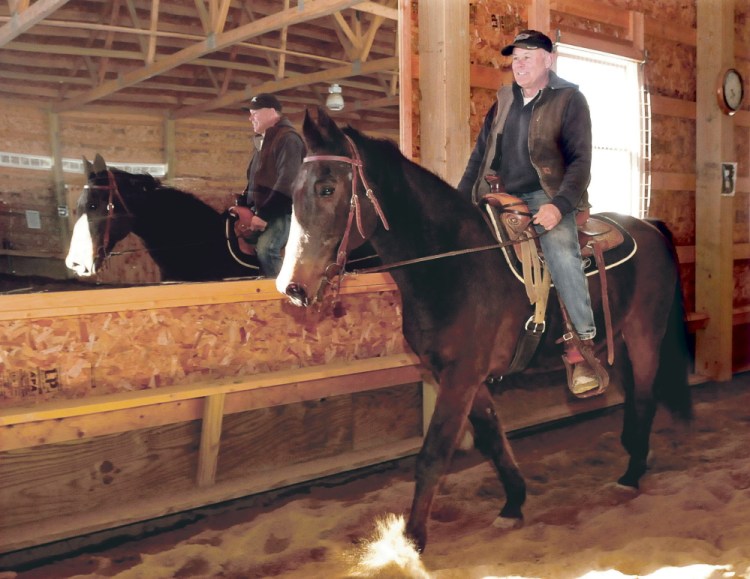

Hight’s friend and longtime Norridgewock dairy farmer Rob Rowbottom is in charge of working directly with Jack, helping him adjust from the fast lane to the pathways of leisure riding. Rowbottom, 62, compared his work with Postcard Jack to that of an elementary school teacher who must approach each school subject from the very beginning or be doomed to failure.

“Postcard Jack is not the norm because he raced for a full career, therefore he’s harder to train, to rehab,” Rowbottom said. “Most of them are out of racing by the time they’re 5. He was 14. What I do is prepare him to be whatever the person whose going to take him on wants him to be — make sure he’s balanced, he’s safe to ride.”

Rowbottom said he is getting Jack ready to move on as a saddle horse, a job that he loves and one that Jack appreciates because it gives him something to do rather than just lounge around and get old in Debbie Hight’s pasture. But Rowbottom said he has to move slowly, adjusting the horse from the adrenaline of the roaring fairgrounds crowd to the quiet clip-clop of a farm trail or arena.

“I’m just learning now myself,” Rowbottom said. “If you tried to bully him — ho — he’d kill you. He just won’t stand for it. He’s very athletic and he’s very smart. The end result of all the ground work is this nice demeanor. It doesn’t not break their spirit — they’re a herd animal. If you’re the leader, they’re fine with it.”

Rowbottom said a racehorse, such as a pacer, is much harder to turn into a saddle horse than a trotter or a thoroughbred horse because they want to pace every time they go out — it’s what their lives have always been — run fast, head high and win.

Work includes the positioning of the head from the upright position of racing down the track to a head down position for a quiet ride along a country path or in a horse barn, such as Hight’s Golden Winds Farm on River Road, where Jack is being trained.

Rowbottom uses the reins as a guide, urging the horse to go forward or back, to the left or to the right and disengaging the hind quarters, so the horse can’t buck or rear up. All this is done without using leverage devices that force the horse into the position.

“He would not back up when we started. They didn’t want him going backward when he was racing,” Rowbottom said. “He never had to bend like that because he always went straight and fast.”

Hight said the retraining effort with Jack got started when she read an article on Nicker News titled “Anatomy of a Wreck,” which described a session similar to one she had with Jack. She contacted the editor of the community website for horse lovers to tell her how that story had resonated with her and ultimately wrote her own column for the publication.

“He started with a crazy, dangerous rescue horse two years ago,” she said of Rowbottom and his work with Postcard Jack. “After about a year, he was nearly safe to ride.”

When retraining a horse, it’s important to go slow and maintain consistency. It takes a lot of patience, commitment and time, according to www.horsechannel.com. People tend to rush into riding an ex-racehorse and attempt to switch the horse’s mindset from the track to a new discipline too soon, according to the website.

“This is when people tend to get hurt,” Lloyd Henderson of the Kentucky Equine Humane Center told horsechannel.com. “They are working with a confused horse that has been trained for a particular purpose. They must first work at the re-training process through lots of patience and communication.”

Rowbottom and Hight agree and have learned a lot from the various websites and horse retraining CDs they have watched.

“We have to re-teach him how to run, how to move, because he’s now more flexible and can make circles and be calm,” Hight said. “What we’re turning him into is a safe rescue horse … who’s got a job and he’s not going to kill someone. Rob feels like he is proceeding faster with Jack because he knows better how to read the horse and how to do some of these other things and they all matter.”

Part of the training is the rounding of the back and disengaging the hindquarters, teaching the horse patience, not to get excited and get him balanced for horseback riding as opposed to harness racing, Rowbottom said.

“We’ve learned that horses don’t really want to be retired — they always want a job — so he’s happy doing this,” Hight said. “On a calm day he’ll make circles and be calm. What we’re doing is turning him into a safe rescue horse. He’s a rescue horse whose got a job: to relearn how to be a saddle horse.”

Not all retired race horses have the same kind of luck, she said. Some end up in rescues, but some head to the slaughterhouse, while others have a good retirement home. A standardbred horse can live to age 30, Hight said.

“We’re just doing it for the good of the animal. We’re not doing it for anything else because there’s no money in this, I can tell you,” Hight said. “He’s 25 but he doesn’t show any kind of lameness. He’s very well cared for. That makes a difference, but there’s a little bit of luck involved, too.”

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

Twitter: @Doug_Harlow

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story