VASSALBORO — Frank Richards can remember when regular algae blooms on Webber Pond made having a lakefront home almost unappealing.

From July until September, for decades, the lake would suffer blooms that turned clear water into a green slurry, fed by a phosphorus imbalance that was the legacy of agriculture and shorefront development.

Some years the bloom was so bad water visibility didn’t get farther than a foot and a half from the surface. People avoided swimming in the lake at the height of the summer. Sometimes Richards, who has been president of the Webber Pond Association for 10 years, would smell a faint odor like that of sewage.

“It would look like a green milkshake,” Richards said, standing recently on his dock on the northeast shore of the lake.

In the past decade, however, the situation has improved dramatically. The water has cleared, and the algae blooms aren’t as frequent or long-lasting. Anglers report the best fishing in decades. In 2009, the lake recorded its best water visibility since records began in the 1970s — 6.6 meters — close to 22 feet.

It’s a remarkable turnaround, won by years of hard work to reduce phosphorus inflow by fixing eroded gravel roads, growing shoreline plant barriers and drawing down the lake’s water level every year.

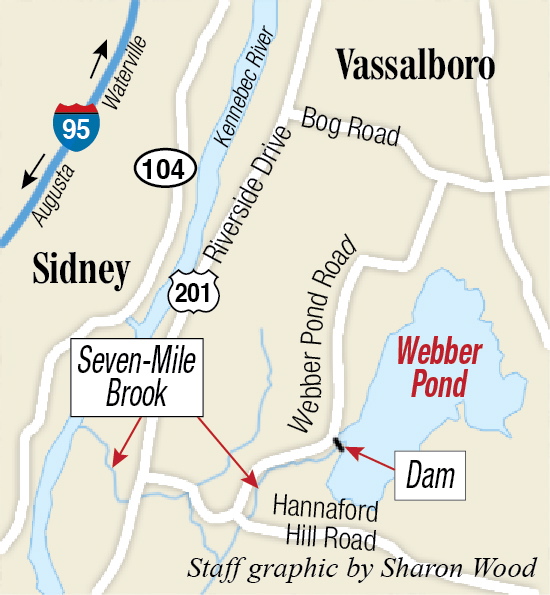

But Richards thinks something else finally tipped the scales — the return of annual runs of migratory alewives, up Seven Mile Brook and into the pond.

Alewives are often called a keystone species. The prolific fish are devoured by virtually every other marine and freshwater fish, bird and mammal. Alewives, also called river herring, once swam up every major river on the East Coast; but industrial development, dams and pollution wound up blocking the runs.

Decades ago, Maine started reintroducing alewives, taking out dams and building fish passages. Now the Kennebec and Sebasticook rivers host the largest alewife run on the East Coast. At least 2 million adult fish make the run past the Benton Falls dam on the Sebasticook River.

Alewives were reintroduced to balance the ecosystem, but they also have helped clean up some of central Maine’s dirtiest ponds.

Adult alewives travel upriver from the Gulf of Maine to breed in freshwater lakes every spring. They spawn millions of juvenile fish that spend the rest of the summer feeding in the lakes before the autumn run to the ocean.

But during their summer feast, the young fish act like sinks and can carry out excess phosphorus that cause algae blooms and poor water quality. The algae, or phytoplankton, feeds on the phosphorus, and is in turn eaten by zooplankton, microscopic animals. Juvenile alewives eat zooplankton, ingesting that phosphorus.

So when the young alewives leave, they carry all that phosphorus they’ve been ingesting out with them. A few generations of migrating fish eventually can make a dent in lakes with excess phosphorus, such as Webber Pond.

A 2003 control plan from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection estimated that the pond needed to remove 532 kilograms, more than half a ton, of annual phosphorus input to keep the phosphorus with the pond’s capacity to hold it and remain healthy.

With phosphorus hidden in the lake’s sediment accounting for more than a third of the amount going into the lake every year, reducing the phosphorus input by that much was doubtful.

But within years of the report, the lake began to improve. The Department of Marine Resources had been stocking Webber Pond with alewives since the 1990s, but the lake didn’t start to see a payoff until around 2005. After a fish ladder was built at the dam on Seven Mile Brook a few years ago, the improvement became even more noticeable, Richards said.

About 366,000 fish now make their way into Webber pond to spawn every year.

“I don’t think anyone had any idea that these juvenile alewives could sequester so much phosphorus and take it out that it would cause the lake to clear,” Richards said.

NOT A CATCH-ALL

In the mid-1970s, Barry Mower, then a young biologist working for the Department of Environmental Protection, studied the effect of alewives on the water quality in Little Pond in Damariscotta.

Among the findings of that study was that juvenile alewives had the capacity to remove between 15 and 25 percent of the annual phosphorus load, Mower recalled in a interview.

“What we found in Little Pond was the key was getting adults and juveniles out and you could remove a substantial amount of phosphorus,” Mower said. If, however, a drought or draw-down of water prevented fish from leaving, there would be no net removal of phosphorus, he added.

Mower, who still works for the department, has since studied alewives’ effect on other bodies of water, including Sabattus Lake and Lake George in Canaan. So far there’s no indication the fish harm water quality, and the Webber Pond example shows some lakes and ponds can benefit from alewives.

Although there have been success stories, people shouldn’t think of the fish as a catch-all solution, Mower added.

“It’s not a magic bullet that’s going to solve every problem overnight,” he said. “It may take a long time or it might not work.”

“If a lake has too much phosphorus for decades, you’re not going to clean it up in just a few years,” he added. “It may not work for all ponds. We don’t know all there is to know.”

Nate Gray, a biologist with the Maine Department of Marine Resources who has spearheaded alewife restoration on the Kennebec River, said that while alewives’ effect on water quality is known, it is “icing on the cake” of a much bigger restoration project.

Since the state is looking to restore alewives only to their native runs, people with concerns about water quality in other parts of the state, such as Belgrade Lakes, shouldn’t be looking to the little fish for a miracle solution.

“Historically, the Belgrades weren’t accessed by alewives,” Gray said. “While the root problem is identical, the potential solution is quite different.”

THROWING A SWITCH

In central Maine lakes where alewives have been reintroduced, however, people are viewing the fish as a potential game-changer.

On Three Mile Pond, just south of Webber in Augusta and China, residents contended with even worse water quality for decades.

Tom Whittaker, the vice president of the Three Mile Pond Association, has lived on the pond for 20 years, and almost every year an algae bloom would start in early July and get progressively worse until September. Conditions were so bad that the pond was treated with copper sulfate in the late 1990s to control algae.

The pond association, working with the China Lakes Region Alliance and the Kennebec Soil and Water District, worked to limit phosphorus any way they could.

“You don’t realize how bad a lake can get until you see Three Mile in the fall,” Whittaker said. “It literally looked like paint.”

Three Mile is connected to Webber through Seaward Mills Stream, and alewives have made their way into the lake. Residents suspected there would be a benefit from the fish, but the suddenness of the change took people by surprise.

In 2012, there was an early bloom. Then, almost miraculously, the lake cleared, Whittaker said. Water quality has improved for the past two years, he added.

“It was like somebody threw a switch and it got clear,” he said.

Volunteers are now working on Seaward Mills Stream to encourage alewife migration and hopefully, improve water further.

Volunteers on Togus Pond in Augusta also are working to return alewives, hoping for the same results; and a major project is in the works to return up to a million alewives to China Lake, the source of drinking water for Winslow, Fairfield, Benton, Waterville and Vassalboro.

But in Unity Pond, the return of the alewives hasn’t had the same effect — at least, not yet.

The body of water is notorious for poor water quality and regularly ranks in the top 10 worst-performing lakes in Maine, said Rick Kersbergen, the president of Friends of Lake Winnecook. A legacy of agriculture has left a heavy internal load of phosphorus in its sediment.

Alewives were stocked in the lake until two years ago, when they started returning naturally, but there hasn’t been a change in quality, Kersbergen said. So far, nothing has changed, and some people on the lake suspect alewives actually are producing poorer water quality because the lake level is sometimes too low for them to get back to the river, which keeps all the phosphorus in the lake.

Even though the lake hasn’t seen a change, Kersbergen hasn’t lost hope for a turnaround.

“We’ve all got our fingers crossed,” Kersbergen said, “but it doesn’t seem to be happening.”

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Twitter: PeteL_McGuire

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.