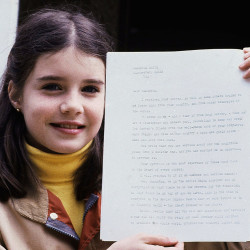

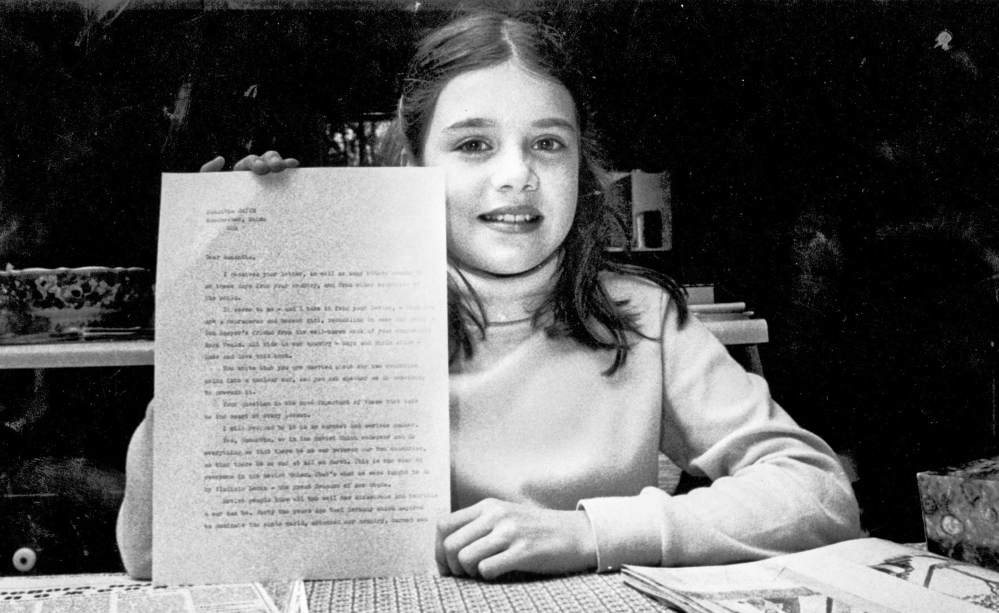

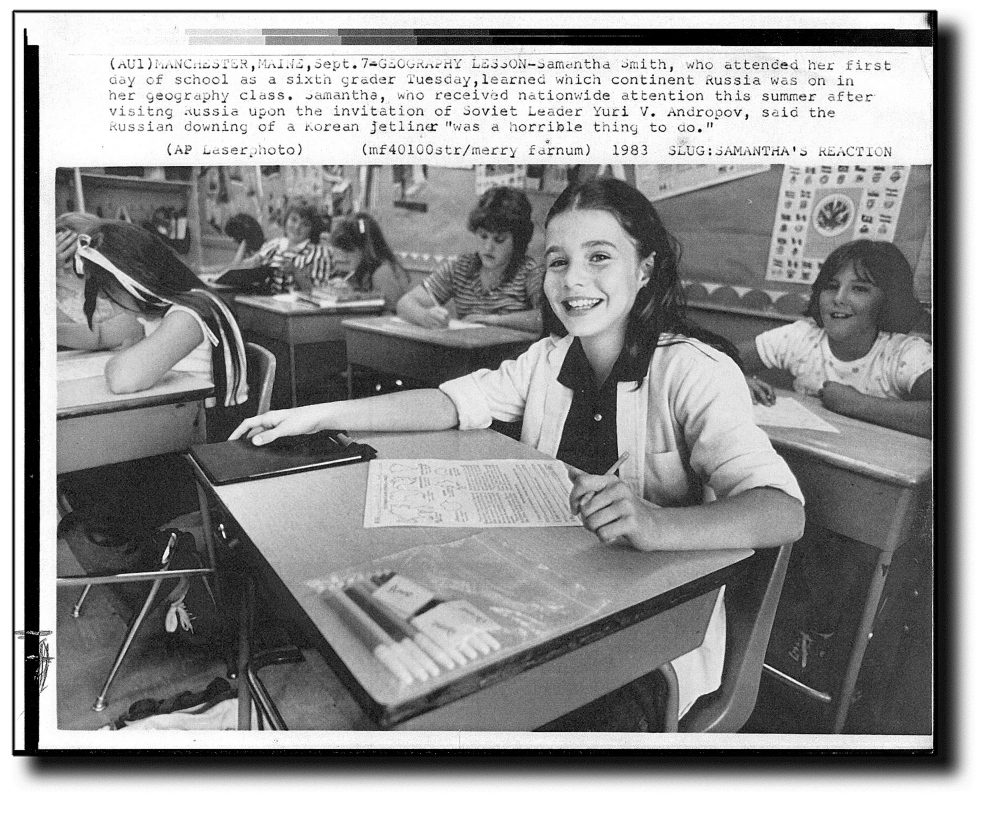

AUGUSTA — Samantha Smith, just 10 years old and a fifth-grader at Manchester Elementary School when she wrote a letter to Soviet leader Yuri Andropov expressing her worry about nuclear war, left behind a lasting message of peace and speaking the truth to people in power.

An exhibit opening on Tuesday at the Maine State Museum seeks to pay tribute to Smith, whose letter prompted a reply and invitation from Andropov to come visit the Soviet Union, which she did in a two-week mission of peace in 1983 that drew worldwide attention.

The exhibit opens on the 30th anniversary of the plane crash that took the life of Samantha and her father, teacher Arthur Smith, when their Bar Harbor Airlines flight crashed and exploded near the Auburn-Lewiston Municipal Airport. They were returning from London, where the then 13-year-old Samantha filmed segments for an ABC television series, “Lime Street,” which featured Samantha and actor Robert Wagner.

While the Soviet Union no longer exists, Smith’s story, which is still taught to many schoolchildren, remains relevant and powerful today.

“I think her story is as relevant as ever,” Laurie LaBar, chief curator of history and decorative arts for the Maine State Museum said after setting up part of the exhibit recently. “Particularly for people who may feel they don’t have any influence, a story like this is refreshing. Because it shows you can make a difference, if you speak the truth.”

In her letter Smith, said she was worried about Russia and the United States getting into a nuclear war, and she asked Andropov what he was going to do to help prevent a war.

“God made the world for us to live together in peace and not to fight,” her one-page, handwritten letter, addressed to “Yuri Andropov, The Kremlin, Moscow,” concluded.

Portions of her letter were printed in the Communist Party newspaper Pravda. Andropov responded with a three-page letter stating he and his people also wanted peace, and inviting Samantha and her family to the Soviet Union.

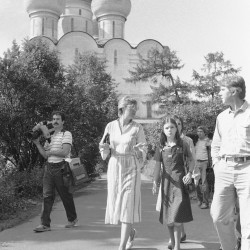

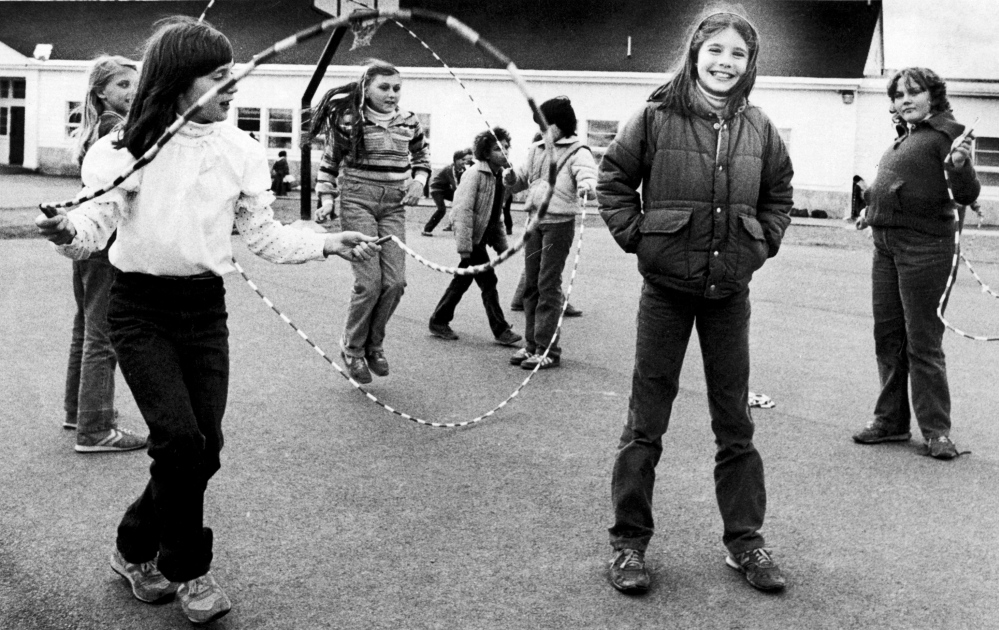

The whirlwind two week trip to the Soviet Union was covered nonstop by the media, as she visited Moscow, Leningrad, and the youth summer camp Artek where spent she time with youths in the Pioneers, a large youth organization.

Critics said the trip was largely intended by the Soviets to be a propaganda tool.

The sweet-faced, easy-going Samantha charmed her hosts and returned a celebrity.

The display planned at the museum will feature about a dozen photographs given to the museum by Soviet photographer Vladimir Mashatin, who was part of the media pool covering the trip from start to finish and who contacted the museum this spring and offered to provide digital copies of his photographs of Samantha’s trip.

“He was part of the media crew that, everywhere she went, they went,” LaBar said. “Everywhere she went there was press, television, reporters, photographers. The U.S.S.R. had nonstop coverage. A huge circus went with her.”

LaBar said they selected photographs that primarily showed Samantha during her time with other children at the Artek camp, where, LaBar said, there were some 4,000 children.

Some of the photographs are of Samantha spending time with Natalia “Natasha” Kashirina, who became fast friends with Samantha during the trip and who, in 1991, came to Maine to serve as a camp counselor at the Samantha Smith World Peace Camp in Poland.

“We want to show her as a girl, a girl going to camp,” LaBar said. “Though it was very different than summer camp here.”

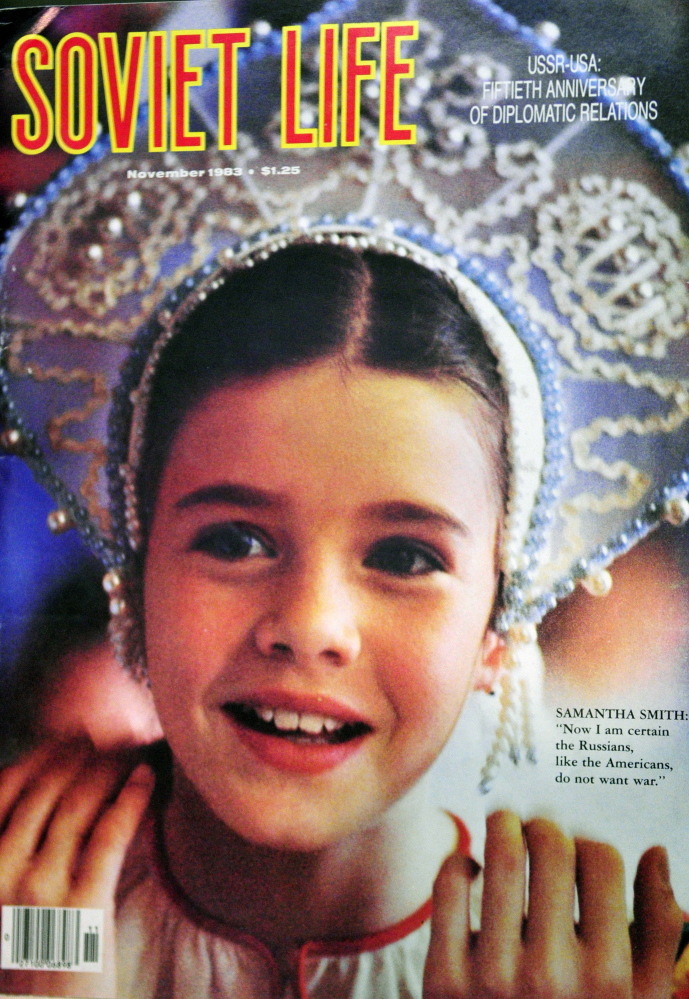

The exhibit also will feature a display case with a traditional Russian dress, a sarafan; and headdress, a kokoshnik, given to her by the Moscow Pioneers; and a copy of “Soviet Life,” a magazine with a closeup of Samantha on the cover.

The magazine cover also includes a quote from Samantha: “Now I am certain the Russians, like the Americans, do not want war.”

The items are part of a collection of items from Samantha’s trip donated by Jane Smith, Samantha’s mother and Arthur’s wife.

The display case with the traditional Russian folk outfit Samantha wore will be just inside the museum’s entrance, while the photographs will be in the main lobby.

LaBar said the exhibit will be up until mid-October, other than being taken down for a couple of days starting Sept. 17 for an unrelated museumwide activity.

LaBar lived in Vermont at the time of the Samantha’s trip to the Soviet Union but said she, like nearly the rest of the world, heard about the trip.

She said many schools, especially in central Maine, teach students about Samantha, and students who come through the museum on tours seem to know about Samantha and her story.

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

kedwards@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @kedwardskj

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story