I worked at the Kennebec Journal for less than a year, but that year was 1983 and it was my good fortune to be one of first reporters to meet Samantha Smith and her parents. I’ve thought of her often in the ensuing years and still experience the sadness of her premature death.

I was operating in the newspaper’s then-Winthrop bureau that April 11, a Monday morning, when my city editor called and said there was a potentially interesting story about a little girl in Manchester who had written to Soviet leader Yuri Andropov about world peace and actually had received a reply. Could I contact her family and drive to their house for an interview that afternoon?

Manchester wasn’t actually on my “beat” list of towns, and I had two other stories to report on already. I considered asking my editor to have a KJ reporter from the main office take the assignment instead, but I was intrigued that this story was just a bit different. Like most people, I had no idea what a flurry was developing in this tense East-West Cold War era.

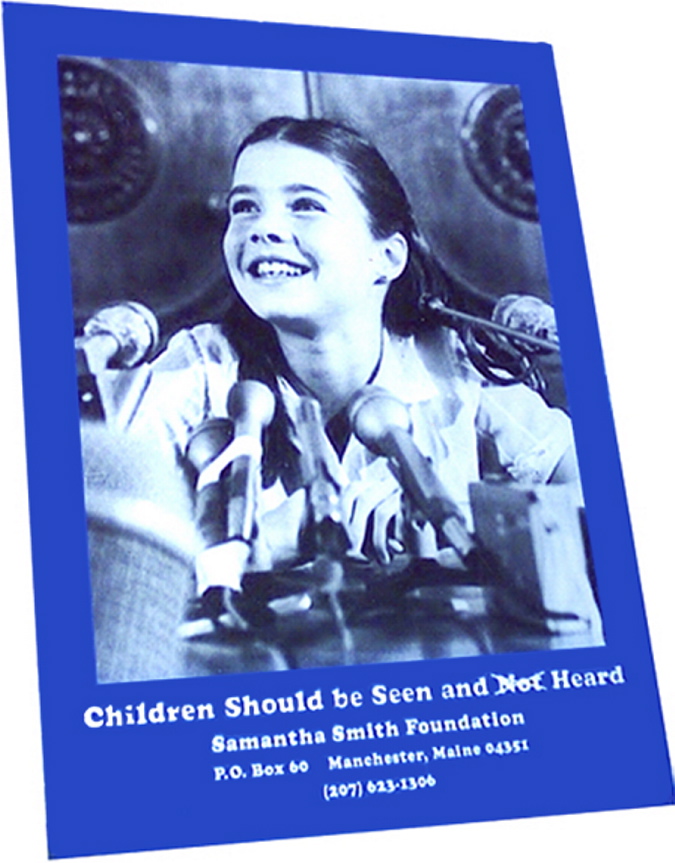

I totally fell for the charms of the 10-year-old Samantha. She answered my questions in a soft but intelligent voice, but she retained the giggles of a girl that age who can melt any adult’s heart. Her parents, Jane and Art, sat by as we spoke, but they had the poise not to intrude on their only child’s big moment.

For some odd reason, I remember Art, who taught English at the University of Maine at Augusta, telling me that he thrown the javelin or discus — I can’t recall which — during his college track days. I left their house impressed with their savvy and realized that if this story blew bigger, Samantha was in good hands.

Which is, of course, what happened. I returned for another interview a few weeks later, when Andropov responded again, this time in a more personal letter, and invited Samantha and her parents to visit the Soviet Union over the summer. By this time, the media crush on the Smiths was growing more intense daily, even in the pre-social media era, but the family handled it wonderfully. Samantha was about to turn 11 but remained a sweet, central-Maine girl. She answered the door on my second visit wearing roller skates.

I have one regret about my reporting about Samantha Smith, and it’s that I lacked the presence to press my editors to accompany Sam and her family to the Soviet Union. The night before she was to depart on July 7, my managing editor said, yeah, I probably should have gone. I just grunted, lacking even a passport at that point. But it would have been quite an experience in those days of nuclear tension.

Still, I was thrilled for the Smiths and followed Samantha’s trip with interest. She charmed the Soviets as easily as she charmed me, and I had no doubt Sam would never again be just a small-town girl. Everybody wanted a piece of her, and she had what it took to become a big success.

The family returned to Augusta on July 26, and, of course, a large horde of media types were waiting to get personal time with Samantha. Two things from that day stay fresh with me: One, how windy it was as some reporters pondered how much the small commuter plane must be bouncing around coming in for a landing at the small Augusta airport; and two, my nervousness because even though we were the local newspaper, it would be difficult finding time with the Smiths to discuss their trip amid the crush of press people.

I underestimated the class of Jane and Art. They graciously allowed me to visit their home first that Monday afternoon, even though Sam was exhausted from the trip and another onslaught of interviews was about to begin. Sam was mostly out of the room enjoying seeing her school friends again, but Art showed me the gifts that Andropov had given to them during the two-week stay. In particular, I remember a beautiful samovar that Art displayed with pride. I got all the material I needed for what would be my final story about Samantha Smith and was forever grateful for their kindness to me as the local KJ reporter.

I left the house after an hour and never saw the family again. Shortly thereafter, I left my job at the newspaper and returned to Vermont where I started in journalism. But I still followed the exploits of Samantha and was almost personally proud of her when it was announced she would be co-starring in a TV series with Robert Wagner. When the news of her and Art’s deaths from a plane crash came in August 1985, I felt immense sadness for Jane at losing her husband and only child. Samantha’s story would never be complete.

Thirty years later, I now live near Washington, D.C., and still hear about Samantha’s legacy from my good friend Joe Owen, who still works at the KJ. Just last month, I visited Maine, and he showed me the Samantha Smith memorial near the Maine State House. It’s a fitting monument for a remarkable girl.

Jack Weible, a former Kennebec Journal reporter, now lives in Arlington, Va., and works at Bloomberg BNA, Arlington, and CQ Roll Call Washington, D.C.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story