First of three parts

WAITE — Wayne Seidl remembers the day a woman showed up at his shop and plunked her paycheck on the counter. She asked him to cash it in exchange for lottery tickets. It had been a hard week, she said.

Seidl, co-owner of the Waite General Store in northeastern Washington County, recalled the woman had three or four kids at home. He told her the money would be better spent on food or clothes for her children. He refused to sell her the tickets. But he doubts it made much of a difference.

“If they don’t buy them here, they’ll go somewhere else,” he said.

Seidl, a former selectman in Waite, population 101, has no shortage of such stories. Another frequent customer, he said, makes a 90-mile daily trip from Calais to Waite to Houlton, buying $25 scratch tickets at every stop along the way. One man routinely spends $200 a day on the lottery. Other regular buyers are on food stamps, unemployed or on welfare, he said.

Seidl’s tiny roadside convenience store, along a lonely stretch of Route 1 in an area where unemployment has often been the highest in the state, sells more lottery tickets per capita than any other in Maine: $1,313 for every man, woman and child in town, according to financial statements obtained under the state’s open records act. Some who buy lottery tickets here are likely just passing through and live in other towns; no records exist on who precisely is playing. But the correlation between unemployment and increased lottery play is no coincidence.

A study of the lottery by Cornell University, conducted at the request of the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting, shows that across the state, lottery ticket sales go up when people lose their jobs. For every 1 percent increase in joblessness in a given zip code, sales of scratch and draw tickets jump 10 percent.

The analysis, conducted with data obtained under Maine’s open records act, adds a real-world example to the long-held axiom that the lottery is a tax on the poor. Recent research in 39 states has shown that lottery sales increase with poverty, and economists have long warned that lotteries prey on societies’ most desperate people, who play disproportionately despite long odds of winning.

“You’re selling to people who are already desperate, or in tough financial circumstances,” said Cornell behavioral economist and professor Dr. David Just, an expert who has researched lotteries across the country and who helped analyze the Maine data. “By promoting the lottery, the state is, in some way, complicit in this.”

A six-month investigation of the Maine State Lottery raises many questions about the games, which the state has long touted as “fun and exciting entertainment.”

Among the investigation’s other findings:

• Residents in Maine’s poorest towns spend as much as 200 times more per person than those in wealthier areas, according to the data. Disproportionate spending by the poor and unemployed has helped to boost ticket sales to $230 million annually, more than what Mainers spend each year on liquor. Though initially reluctant to play the lottery when it was first introduced more than 40 years ago, Maine residents now spend an average of $173 per person, placing them in the middle of the pack nationally in 2014. By comparison, Rhode Islanders spend $794 per person annually on lottery tickets, and North Dakota residents just $36, according to data from the North American Association of State and Provincial Lotteries.

• Since 2003, the state-run lottery has more than tripled its advertising budget, invested in sophisticated market research to better target new customers, and installed flat-screen TVs in stores to encourage impulse buys, according to interviews and documents obtained by an open-records request.

• Because the lottery pays for itself through ticket sales, the Legislature exerts virtually no oversight over the process. Most budget and marketing decisions are made internally, with little or no review by legislators, who in 2007 requested that the Legislature’s investigative arm conduct a yet-to-be-completed assessment of the lottery’s operations. “They basically run their own business,” said state Rep. Louis Luchini, D-Ellsworth, co-chairman of the committee that oversees the lottery.

• Despite promoting the lottery over decades, the state has never studied its impact on the lives and finances of the poor and unemployed, who spend disproportionately on the lottery. State lottery and health officials interviewed said they have no data on addiction rates and have no plans or funding to gather it, and instead must rely on data from other states, they said.

When presented with the data, state lottery officials said the numbers don’t tell the whole story. They emphasize that the games are voluntary and that the majority of revenue is returned to winners and to the state’s general fund, to the benefit of all Maine people.

The lottery transfers an average of $50 million per year of the $230 million to the general fund, the state’s primary operating budget, money that would otherwise need to come from cutting state services or raising taxes, officials said.

“That money helps with education, conservation … all those things and services that state government provides,” said Tim Poulin, the lottery’s deputy director. “And if the players can pocket some money, that can make a substantial difference in their life.”

WHO PLAYS?

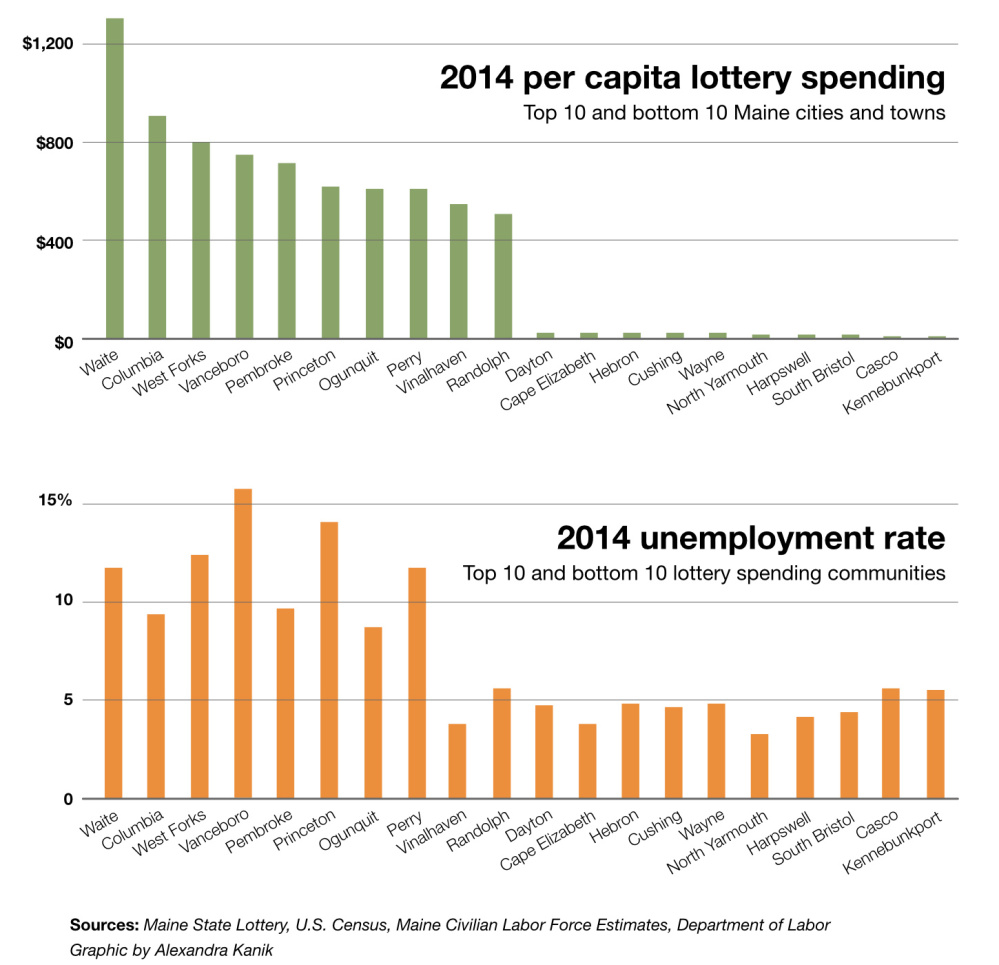

Of the 10 towns whose residents spend the most on lottery tickets, six are in Washington County, the state’s poorest county: Waite, Columbia, Vanceboro, Pembroke, Princeton and Perry, where players spent a minimum of $600 on scratch and draw games in 2014, an analysis of lottery data show.

Store owners in those towns said they were not surprised by the data. But they had mixed opinions on why Washington County residents stand out.

“People here rake blueberries, pick potatoes, make wreaths, snowplow or lobster,” said Wade Green, owner of Delia’s, a small grocery store in Columbia, where lottery sales equal $916 per person annually. “It’s all a gamble, just like the lottery.”

But research and data suggest poverty also plays a key role.

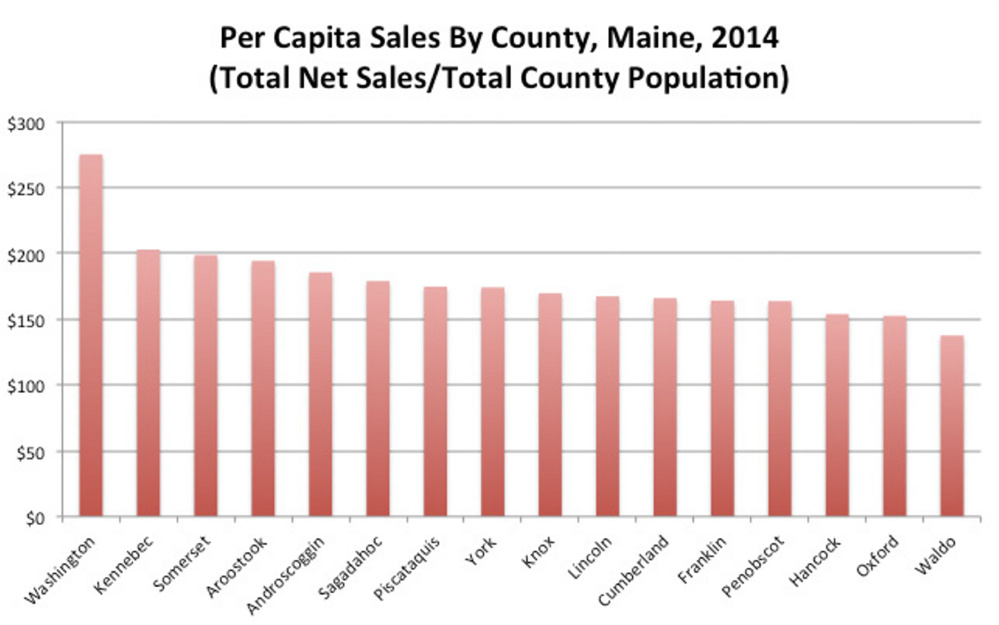

Residents of Washington County, which has the highest rates of poverty and unemployment in Maine, according to 2013 U.S. Census data, spend $275 per person per year on lottery tickets, more than $100 more per year than residents of either Cumberland ($166) or York counties ($174), among Maine’s wealthiest.

In the Washington County town of Waite, the $1,313 per capita spent on lottery tickets in 2014 contrasts with the wealthy coastal town of Kennebunkport, where the per capita spending was just $6, the lowest in the state. One in five families live in poverty in Waite; fewer than one in 100 are poor in Kennebunkport, 2013 Census data show.

“Years ago, we used to sell scratch tickets, but we got rid of them,” says Pamela Hutchins, a business manager with Bradbury Bros. Market in Cape Porpoise, a waterfront Kennebunkport neighborhood. “Our clientele has changed. Most of this town is very wealthy. There’s just no demand anymore.”

Cape Elizabeth, where residents spend just $25 per person per year on lottery tickets, also has one of the state’s highest per capita incomes, $53,505, and one of the state’s lowest unemployment rates, at just 3.9 percent, according to 2014 Maine Department of Labor statistics. Unemployment in the 10 towns that sell the most lottery tickets per person is nearly double that of the 10 towns that sell the least, according to 2014 data from the Maine Department of Labor.

“The bottom line is, a spike in unemployment means a spike in lottery sales,” said Cornell’s Just.

Just’s research in 39 states, over 10 years, corroborates the findings in Maine: Bad times, the evidence shows, leads desperate people to take their chances on the lottery.

State officials said they keep no data on such trends in Maine, but questioned whether other factors, such as proximity to New Brunswick, whose residents sometimes cross the border to play Maine’s lottery, might boost sales.

Just acknowledges that geography may create outliers, but he said the quality of the data in Maine, and the statistical clarity of the relationship between unemployment and lottery sales, is unmistakable. “You just can’t attribute it to anything else,” he said.

The bigger question, he said, is what it means for the people who play the most.

“There are some people who do this for fun and then a small group for which this ends up being really massively damaging,” Just said.

ADDICTED TO FUN

Shelley Arsenault of the Farmer’s Union store in Perry, population 889, knows most of her best lottery customers in this small Washington County town by name. Residents here purchase $615 per person annually.

Monica Altvater of Perry is a regular. On a rainy summer morning, Altvater bought more than a dozen scratch tickets at the counter. She likes “Cash Winfall” and “25X the Money,” a $10 instant ticket that promises rewards of as much as $250,000.

“I won $15, spent $150, and I’m not even done yet,” she said, tossing losing tickets into the trash. “I may drop my whole paycheck here today.”

Altvater said she plays the lottery for the fun of it and holds hopes of winning big, despite her bad luck that day. But state lottery officials do not know how such habits affect the lives of such avid players.

Research into the social impacts of the lottery, said Deputy Director Tim Poulin, falls to the state’s Department of Health and Human Services, not the lottery, which falls under the Department of Administrative and Financial Services. But, Christine Theriault of DHHS’s Office of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services said her office lacked funding to study the question.

The state spends $100,000 on problem gambling initiatives, Theriault said, but that money is spread across a wide spectrum, including higher-profile casino gambling.

“Somebody can be just as addicted to lottery tickets as they are to going to a casino, or sports betting, or card games, slot machines, poker,” Theriault said. “Unfortunately, we don’t have data that tell us how many people in the state have a problem. It’s a gap we have.”

What remains clear, however, is that players’ hopes are often misplaced. The most favorable odds, sometimes as encouraging as about one in five, are for small winnings, often break-even prizes which experts say are critical to keep players coming back. The big jackpots, which also drive sales, offer extremely long odds. The odds of winning the Powerball, Maine’s best-selling draw game, for example, are 1 in 175 million, according to the lottery.

A person is 14,000 times more likely to get struck by lightning in his or her lifetime, the National Weather Service estimates.

Arsenault, who said she has worked at the Farmer’s Union in Perry for 26 years, says the odds hardly matter to many of her customers. With so many tickets on offer – she now sells 28 games where once there were just one or two — the details are lost in the frenzy.

“It’s gotten absolutely crazy,” she said. “I’ve seen it where people will come in, buy a gallon of milk and not have enough for a scratch ticket. They’ll turn around and put the milk back.”

Researcher Blake Davis contributed to this report.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story