WISCASSET — Angelique Delano remembers the odd request from her teenage son, Gavin Clark, that is now seared into her memory.

It came a few weeks ago, during one of the rare serious conversations she had with him.

“He told me to stop telling him I was proud of him,” said Delano, 35. “I’ve been racking my brain, trying to figure it out. I don’t know if he’d already started giving up.”

Gavin was 15 when he died alone in his bedroom from an apparent suicide this month. His death has devastated his family and the Wiscasset community.

During an emotional candlelight vigil at Wiscasset Middle High School that was held barely 48 hours after his death, mourners spoke at first about Gavin and his life.

But then talk turned abruptly to bullying, with people blaming his death on a hostile school atmosphere, according to several people who attended the event.

Yet interviews with Gavin Clark’s friends and family reveal that he was affected by forces in life that were far more complex, influenced by family circumstances out of his control, shadowed by poverty, drug abuse, a deep family history of suicide, and his own thoughts of self-harm.

Over the years, Gavin had grown into a sensitive, fun-loving young man, but one who struggled to fit in at school and had intense anger toward his absent father. He had close friends, but was goaded by other students about his learning disabilities, causing him to lash out.

Adults who cared for him said they were concerned about recent changes in his attitude and behavior, but he didn’t like therapy and didn’t take his anti-depressant medication long enough for it to work. Not until his life slipped through their fingers did the people who loved Gavin realize how alone he felt.

• • • • • •

Angelique Delano met Gavin’s father, James Clark, about 16 years ago. She was a teenage waitress at the Rocktide Inn. He was living with another woman, but the two quickly connected.

“He showed up one night and he never left,” Delano said.

They would spend 12 years together, on and off, when Clark was not in prison or jail.

Both were heavy drinkers and drug users, and after less than a year together, Delano found out she was pregnant. She sobered up during her pregnancy, but her boyfriend’s abuse of alcohol and opiates continued. Sometimes, he’d turn violent.

“We loved each other very much but it was a volatile relationship,” she said.

These habits and others landed him in legal trouble frequently, public records show.

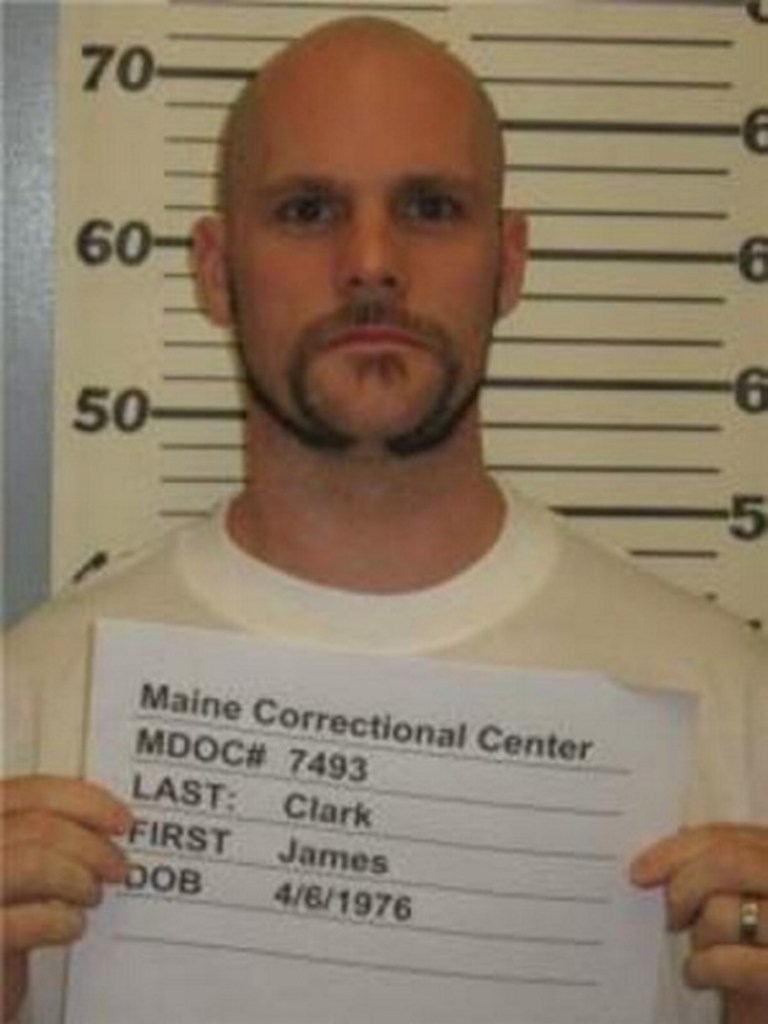

Clark’s criminal record stretches to 47 pages, and includes drug offenses, motor vehicle violations and multiple assault charges dating to 1999.

In 2013, he was sentenced to four years at the Maine State Prison in Warren on felony domestic violence and motor vehicle charges, in addition to four misdemeanors. His earliest possible release date is December 2016. Clark, now 39, declined a request by the Maine Sunday Telegram to be interviewed for this story.

Delano said Clark was absent from his family’s life from the start. He was in jail during the births of both of his children.

Gavin J. Clark was born Oct. 22, 1999. Immediately, little Gavin was a child in constant motion. It seemed he was born to ride, bike, skate and slide on whatever wheeled vehicle he could find.

He was only 2 years old when his parents gave him a miniature four-wheeler. He was still too young to give up his pacifier, but old enough to relish bombing around his family’s yard, sucking on the binky.

When Clark wasn’t in prison or jail, he tried to be present for his children, but as that time dwindled, the pressure to provide for the family landed on Delano. Clark was locked up again when his second son, Mason Clark, was born on Nov. 7, 2005.

“James was ‘fun dad,’ ” Delano said. “The kids always had toy boxes full. They always wanted to see him.”

The couple finally split for good about four years ago, around the time Delano filed a protection from abuse order in Lincoln County court in Wiscasset after a fight on a Wednesday night in January 2010, according to court records.

With Gavin, 10, and Mason, 5, looking on, Clark pinned Delano to their bed and started choking her, Delano wrote in an account of the fight.

Gavin went to find a phone to call 911, but his father grabbed it first and left the house with it, preventing Delano or anyone else from calling police.

“I am fearfull (sic) that James Clark will return to my home and assult (sic) me in frount (sic) of our children again,” she wrote in a Jan. 29, 2010 report. “I am scared to have James in my home again.”

The next day, police were called for a reported violation of the protection from abuse order; three days later, James Clark was charged with domestic violence assault and eventually found guilty.

Delano said if it had not been for her elder son, she might never have left the relationship.

“It was Gavin who said to me, ‘Mom, I think Dad is going to kill you,’ ” Delano said. “That day I went and got a protection from abuse order. It was the only time I had a fight in me to get away from that.”

• • • • • •

Delano raised her boys in a mottled-gray mobile home on West Alna Road in Alna, about 4 miles north of Wiscasset village, and only about 40 yards from the home of Delano’s mother, Deborah Churchill, 55.

While Delano worked long hours as a home health aide, the family helped babysit her kids, including two of Delano’s aunts; Churchill; and Churchill’s son, Matthew Churchill.

As Gavin grew up, he developed into a sensitive, active, goofy kid.

He didn’t like killing bugs if he could avoid it. He loved animals, and is seen in family photos draped over one of his grandmother’s horses, or asleep on a mat with two dogs curled nearby.

As Gavin entered kindergarten, he became close friends with another boy, Alex Taylor, Delano said. It would be an important relationship for Gavin, who became a fixture at the Taylors’ home, and was accepted as another son.

Dave and Deb Taylor treated the boys the same, giving equal space for presents for Gavin under the Taylors’ Christmas tree.

Even though he was diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and had to endure painful injections of medication, Gavin loved to skate and scooter, performing stunts around town with friends.

The Taylor family helped Delano buy the bicycles, skateboards and scooters that people around Wiscasset associated with the blond-haired teenager.

And when the Taylor family went away on vacation, Gavin came along, too – even, one year, to Aruba.

But the dark influences in Gavin’s life didn’t go away.

In addition to his immediate family’s struggles, Gavin saw death and tragedy that remained in the background. James Clark was 12 when his father had committed suicide, Delano said, and a relative of Churchill’s, Gauge Barnes of Wiscasset, killed himself in October 2009, at age 14. Barnes’ mother killed herself on Mother’s Day 18 months later at her son’s grave.

Gavin had his own dark thoughts, too. On more than one occasion he told his mother that he wanted to shoot himself or drown himself in the tub.

At school, Gavin struggled to read, write and spell, and was diagnosed with a learning disability. He was placed in the Wiscasset alternative education program, Delano said.

At first, the program was in a separate building where the superintendent’s office was also located.

But this school year the alternative education program was moved into the same building as the middle and high schools, placing Gavin back into the general student population, and according to his family, in the path of other kids who teased him about his learning disability.

• • • • • •

The taunts at school took on an unfortunate but familiar refrain: The special education class that Gavin attended was known by other children as the “sped shed,” Delano said. Students even created a “sped shed” song and sang it in front of Gavin and his girlfriend, who was also in the alternative education program.

In the last two school years, Gavin was suspended twice by the school for fighting. Both times he was reacting to other kids’ taunts, his mother said.

Dr. Heather Wilmot, the Wiscasset school superintendent, declined to discuss the specifics of Gavin’s case because he is a minor, but said the district takes bullying seriously, and has programs and supports in place for students.

“I can’t even describe the trauma,” said Wilmot, who oversaw several days of grief counseling at the school following Gavin’s death.

Some have blamed his suicide on the bullying he endured; at a memorial last week attended by hundreds of people, many wore anti-bullying buttons.

Yet Churchill and Delano believe there was no single factor that can explain his death, despite the difficulty he had with other kids.

“I think it was a big combination of things,” Churchill said. “I know he was stressed. He was angry about his dad being in jail, and how he can’t seem to make a change.”

That thinking follows much of the recent research on youth suicide – that although bullying can play a role in a suicide, placing too much blame or media attention on it as the single cause can mask the complexity of emotions that lead someone to feel hopeless and alone, said Heather Carter, a senior trainer for the Maine chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness who has spent eight years working on youth suicide prevention.

For the last two years, Carter has helped implement a state law requiring every school employee to receive training to recognize risk factors for suicide. She said a commonality in Maine is that young people are not being adequately identified as needing mental health services when they’re struggling, plus there’s a lack of access to those services even when the need is identified.

Although she does not know the details of Gavin Clark’s story, Carter said that some of Gavin’s early life experiences fit the list of risk factors that can contribute to suicide, including exposure to domestic violence, family stress, the suicide of close relatives, and family members with drug and alcohol problems.

And when someone is overcome by those issues, she said, bullying or some other acute personal stress can nudge someone to take drastic action.

“When a youth dies of suicide, there is often a tendency to point a finger,” Carter said. “We don’t want to normalize the connection between suicide and bullying. There are a lot of risk factors. Just because someone is faced with a lot of risk factors doesn’t mean they’ll die by suicide.”

• • • • • •

This summer, history seemed to repeat itself for Delano. Six months earlier, she had hastily married a former high school classmate. But he, too, appeared to be an alcoholic who over time turned on Delano and her sons. Gavin despised the man, and in May, when Delano finally turned him out for good, she broke her sober streak.

She felt suicidal herself, and after counseling and rehab, cleaned up for her family. But when she returned, Gavin was smoking cigarettes. Usually he was sensitive about personal hygiene, but he had stopped showering and changing clothes – warning signs to his family.

Delano had also begun allowing him, with his doctor’s knowledge, to use medical marijuana to dull the pain from his rheumatoid arthritis. Her decision disturbed other people, Delano said, but she saw Gavin smoking weed as a far lesser evil than trying to numb his pain with Oxycodone or some other opiate.

As Gavin withdrew further, his schedule at school became less consistent, Delano said.

Delano would leave around 7:15 a.m. to work a janitorial shift at the Department of Marine Resources in West Boothbay Harbor, a 35-minute drive. Gavin would get up around 7:30 a.m. to make sure his little brother made it onto the bus to school, but then Gavin, unsupervised, would often return to bed, showing up at school later at his discretion. Sometimes a school counselor with whom Gavin had a close relationship would pick him up. Other times his grandmother would drive him.

“He said all the time he was done with school,” Delano said.

When she tried to engage him in a serious conversation, he would shut down, she said.

Churchill, Gavin’s grandmother, said she saw his behavior change over the summer, and he seemed to become more impulsive. She wondered if he had some undiagnosed mental health issue. Gavin saw a therapist for about a month, and was prescribed Zoloft, which is used to treat depression and anxiety. But the regimen didn’t stick. Gavin did not connect with the therapist, and did not take the medication regularly enough for it to be effective.

Then a few weeks ago, Gavin told his mother to stop telling him that she was proud of him.

Gavin’s last text message was to his girlfriend, his mother said. The two had been arguing, but the girlfriend cut the conversation off, telling Gavin that she would talk to him tomorrow.

Then he sent a chilling reply, according to Delano: What if I’m not here tomorrow?

Now Delano can’t stop thinking about the warning signs, wondering what she could have done differently.

“Even though he had threatened things with suicide before, I never took it seriously,” Delano said. “Everything sticks out in my mind now. I honestly haven’t stopped thinking about it, and I probably never will.”

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.