WATERVILLE — David Solmitz has found his place in the world after spending a lifetime exploring the past, fighting for justice in the present and coming to terms with the suicide of his father, a Nazi Holocaust survivor, and the death of his first wife and a son in a car crash.

Finding clarity and understanding is an ongoing process and not easy, but he is finding peace in the journey.

“I feel somehow embraced by not only all the experiences of my past life — my parents, my first wife, my family, my children — and all the experiences that have brought me to where I am, happily, now.”

Writing has been a source of discovery, of clarity and healing for Solmitz, 72.

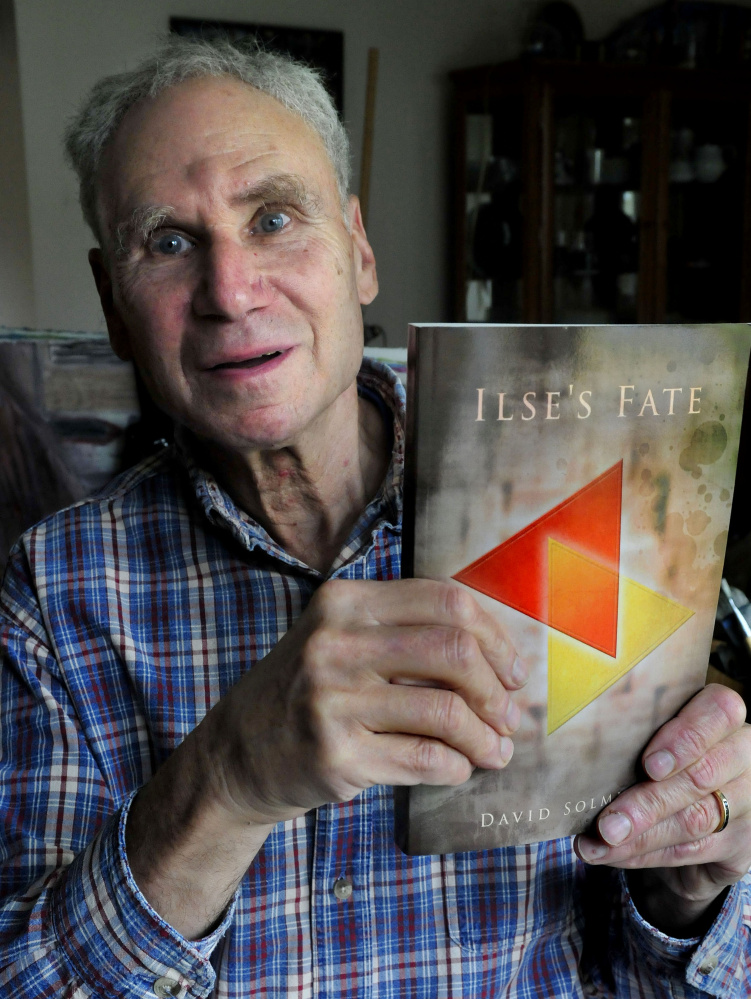

The author, educator, artist and human rights activist will read from his third book, “Ilse’s Fate,” at 2 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 8, at Waterville Public Library. Set in Germany between 1913 and 1945, the book is a fictional account of a girl who, through ignorance and insecurity, is drawn to Nazi ideology.

While a work of fiction, it incorporates the experiences of Solmitz’s parents, who were German Jews, and their friends and family before and during the Nazi Holocaust.

“My reason for writing this book is, I feel, twofold,” Solmitz said recently in his Waterville home. “I’ve always felt, I would say, anxious and maybe some prejudice towards Germans because of what they have done to my family and friends and relatives, so I feel I can’t live with those kinds of feelings.”

Solmitz had explored his feelings in a previous book, “Piecing Scattered Souls: Maine, Germany, Mexico, China and Beyond,” a memoir. With “Ilse’s Fate,” published in July by New York City-based Page Publishing, he continues to explore — in writing — the contrast between good and evil through the fictional character Ilse.

“I believe that all of us have good behaviors and bad behaviors, and sometimes out of ignorance or misunderstanding or lack of knowledge, our behavior becomes bad. We do bad things.”

Ilse is a character who grows up in a manor in southern Germany with her father after her mother dies in childbirth. She is a lonely girl but finds solace and joy in animals, birds and flowers and becomes close to the manor’s gardener. She also takes violin lessons from a very kind teacher. At one point she and her father move to a small apartment in Munich, and that is where the trouble begins. He is cruel to her. She is required to do the cleaning and cooking and to polish his shoes. She is teased at school because she does not fit in. Isolated and disconnected, she becomes involved in the Nazi movement and later marries a young Nazi officer.

“What I’m trying to point out in the novel is the contrast between good and evil,” Solmitz said. “She is a sensitive and good girl who, out of insecurity and probably ignorance, turns toward the Nazi movement.”

In the afterword of his book, Solmitz writes about his parents — his father, Walter Solmitz, who was incarcerated at Dachau in 1938, and his mother, Elly, who was tenacious in her bid to get him released. He was, and they moved to the U.S., ultimately settling in Brunswick, where his father taught philosophy at Bowdoin College.

An only child, Solmitz befriended poor children in Moodyville, a less affluent section of Brunswick, and launched an anti-poverty program to get townspeople to pitch in and help the residents of Moodyville renovate homes and improve the neighborhood. Later, Solmitz planted petunias in traffic islands built in the middle of Main Street in Brunswick, a project the city has continued.

Solmitz graduated from Brunswick High School in 1961 and studied history at Bowdoin College, graduating in 1965. He also earned a master’s in education from Goddard College in Vermont.

Solmitz’s father committed suicide in the summer of 1962 after struggling with survivor’s guilt and depression.

“Even though he was in Dachau a short time, he never really recovered emotionally from the experience,” Solmitz said.

Solmitz taught in Switzerland, China and Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In 1969 he landed a job teaching social studies at Madison Area Memorial High School where he stayed for 30 years.

He sought to instill in his students a love of learning, to expose them to the arts and to help them learn the importance of social activism and humanity. Solmitz also has taught at Kennebec Valley Community College in Fairfield and at Thomas College in Waterville.

His book “Schooling for Humanity: When Big Brother Isn’t Watching” is about both the difficulties and joys of teaching in a small rural school, where he often found himself butting heads with the administration.

In 1985 he sued the school district for prohibiting him from having a lesbian guest speaker during Tolerance Day. The case went to the Maine Supreme Court, which sided with the school, saying the school board has the right to decide curriculum.

Solmitz’s first wife and son died in a car crash in 1978. While in China, Solmitz met his present wife, Jing Ye, who survived China’s Great Cultural Revolution. She is a psychotherapist at Colby College and practices tai chi, chi gong and meditation.

“This has been just a wonderful marriage,” he said.

Through many experiences, Solmitz has worked through deep feelings of anxiety and prejudice toward a culture that promulgated atrocities on his family and friends.

When he was writing his first book, for instance, he met a man with whom he became good friends and who helped him research.

Solmitz and his wife are hosting a Russian woman in their home who is in her second year as a teaching assistant at Colby and shares an office with a young man from Germany.

“She plays piano and he plays violin and we’ve spent wonderful times together,” Solmitz said. “He’s a young, energetic, very gifted, very intensely deep young man. It’s such a joy to see a young German who is just so utterly enthusiastic about music, about his studies, his work. This has been, really, a wonderful experience.”

Solmitz’s mother was an artist who, while a young woman in Germany, studied at an art conservatory but was kicked out because she was Jewish. She was not able to complete her studies. Solmitz continues in her footsteps as a painter of watercolors.

“In a sense, as I grow older and look back over the years, I begin to see my place in the world. At least I’ve gained some understanding and maybe some insight that gives me more confidence in a world that really is in tremendous turmoil at this point. It’s always an ongoing process, and we gain wisdom through our experiences, through suffering, and we gain more understanding.”

Amy Calder — 861-9247

Twitter: @AmyCalder17

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.