CHELSEA — The helicopter mission to extract or “exfil” an Army Green Beret Special Forces unit on a clandestine mission in Cambodia took place on Feb. 20, 1969.

But Ron Brodeur, now 70, recites every detail as if it were yesterday.

Less than two weeks ago, Brodeur and his fellow gunner/crew chief aboard that mission received long delayed Silver Stars for their valor under fire on that day 46 years ago.

Brodeur and Eric Roberts II, who lives near Houston, Texas, were at the Pentagon to receive the military award Dec. 17. There the two Green Hornets, members of the 20th Special Operations Squadron, reminisced about that particular mission and hundreds of others during their time in the Air Force in Vietnam.

“Our job was reconnaissance,” Brodeur said on Saturday as he sat in the sun room of his Chelsea home. “We put Army Green Berets into the jungle in Cambodia, and when they got into trouble, they were exfilled or taken out.”

The Air Force crews flew UH-1 F/P helicopters, which Brodeur frequently referred to as airplanes. Eight helicopters were kept at the forward operations base.

“We lost quite a few airplanes and crew members while we were there,” Brodeur said.

Brodeur, who spent a total of 30 years in the Air Force before retiring Dec. 31, 1992, as a chief master sergeant, said the missions from Vietnam to Cambodia were “super classified,” and some remain classified. Brodeur had enlisted in February 1963 in Fall River, Massachusetts. At age 17, he was following in his older brother’s footsteps.

On Feb. 20, 1969, Brodeur, Roberts and their pilot and copilot, were sent to extract one of the Green Beret units that was under heavy fire and had nowhere to flee, hemmed in by “a river on one side and the jungle and bad guys on the other three corridors,” Brodeur said. “The site they were on was being mortared by North Vietnamese regulars.”

The Green Hornets arrived amid chaos, but were able to locate the unit.

“The LZ (landing zone) was on fire,” Brodeur said. “There was smoke, and a lot of the trees had blown down from the mortar fire. We couldn’t land, so we had to hover and throw out the 25-30-foot rope ladders.”

The ground team had to climb to safety after hooking their gear onto a ladder rung.

In the meantime, Brodeur and Roberts were firing their machine guns while balanced on the skids on the two sides of the aircraft.

“We were getting ground fire, and then one of the team guys blew up a land mine on the way to the helicopter to try to slow the bad guys,” Brodeur said. “Eric was blown into the helicopter, and it blew me out of the helicopter.”

Brodeur ended up below the skid, dangling from his gunner’s belt and worrying about Roberts.

“As I was getting back up to the machine gun, I looked back over my shoulder and I couldn’t see him,” Brodeur said. “He wasn’t there.”

It turned out Roberts had disconnected his tether and was walking along the skid on the other side of the aircraft to shut the copilot’s door, which was blown open by the explosion.

Then Roberts returned, hooked up again, and the two went back to their positions.

“It all happened very quickly,” Brodeur said. “We continued firing our machine guns, and we helped the guys get in the airplane at the same time.”

Everyone got out without serious injury, Brodeur said. The team’s radio man had been hit, but it just put a hole in the FM radio he was carrying.

“Fortunately he didn’t need it any more,” Brodeur said.

When the helicopter arrived back at the forward operating location, the squadron commander told the pilot to put everybody in for the Distinguished Flying Cross, but the wing commander told the squadron commander to upgrade it to the Silver Star.

That’s when the documentation for the gunners’ awards was somehow lost.

The pilot and copilot received their Silver Stars in December 1969.

“Nothing happened with the rest of us,” Brodeur said.

Later, in 1983, both he and Roberts received the Distinguished Flying Cross, but not the Silver Star.

Brodeur credits Roberts wife, Sue Roberts, with persevering to ensure the men received the medal they deserved. Sue Roberts started her efforts in 1971. Brodeur said that during the Dec. 17 medal ceremony, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, Gen. Mark A. Welsh III, praised Sue Roberts for all her work gathering the documentation.

“Since the U.S. Air Force became an independent service in 1947, we’ve presented 285 Silver Stars,” Welsh was quoted as saying in a news article about the ceremony that appears on the U.S. Air Force website.

“That’s not a whole lot when you think of all the combat sorties and contingencies we’ve participated in,” Welsh said in the article. “One hundred and five of those were given from the Vietnam conflict — soon to be 107. This is a very select group of warriors for a reason. It’s presented for gallantry in action against enemies of the United States.”

More than 100 people, including Brodeur’s son and his wife who live in Minneapolis, watched the two men get their medals.

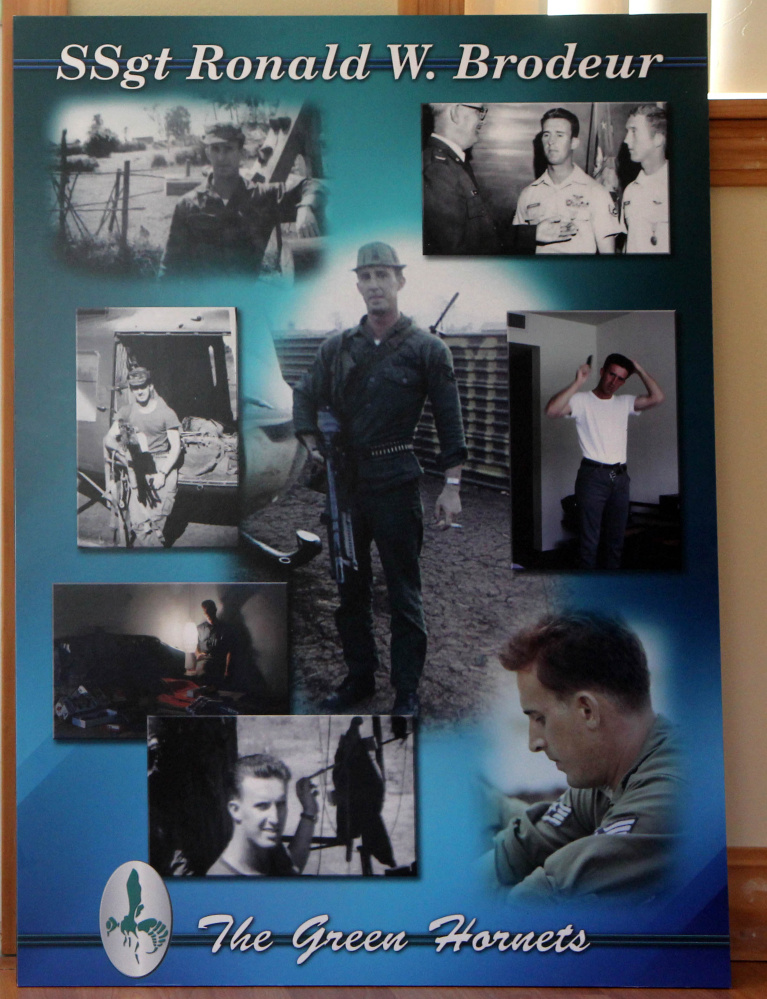

Along with the medals came presentation plaques and posters about the mission and about both men.

“It was pretty exciting,” Brodeur said. “They did a heck of a job putting the ceremony together.”

The attendees also received a VIP tour of the Pentagon.

The pilot and copilot from the mission are both deceased. Brodeur said most of the pilots at the time were former B-52 pilots, majors and lieutenant colonels much older than their gunners/crew chiefs.

Brodeur spent a total of 27 months between 1968 and 1972 in Vietnam taking part in some 1,500 sorties and amassing more than 700 flying hours.

“That’s what we did for a living,” he said. Once the missions were completed, the crew chiefs spent their time fixing the aircraft to get ready for the next day.

He recalled another mission with Roberts to rescue a team. They were accompanied by another helicopter plus gunships and had to hover down through three layers of jungle canopy trees. “The bad guys opened fire, and we lost most of our electronics and three of our four radios,” he said. “We were basically out of commission.”

The other helicopter went into rescue the team and got shot up. Then it caught fire and was guided to a landing zone about five miles away before the engine quit and the aircraft tipped over into the landing zone, trapping the left side gunner under the aircraft.

The three other men were able to get out before the ammunition blew up. The trapped gunner’s remains were recovered later.

Brodeur was also on a recovery mission in November 1968 that resulted in the pilot of another aircraft, Capt. James Fleming, receiving the Medal of Honor.

Brodeur’s last assignment was as senior adviser to the wing commander at Loring Air Force Base, home to the 42nd Bomb Wing and its complement of B-52 bombers and KC-135 tankers.

“I didn’t think I was going to get to deploy again, and we went to Desert Storm,” Brodeur said. That was in August 1990. “We took the whole bomb wing, the 42nd, to Diego Garcia in the middle of the Indian Ocean.”

Brodeur’s air time was limited to a couple of tanker flights while he was there.

“I was too old,” he said.

While he and his wife, Betty, are originally from Massachusetts, they now live in Chelsea. Brodeur spent more than seven years working for the state Department of Labor at the Augusta Career Center and the Bureau of Employment Services Rapid Response Team, then based in Hallowell. He retired from there in 2003.

Now he serves as treasurer for the DAV, Disabled American Veterans, Department of Maine, as well as treasurer and adjutant for the John F. McPherson Chapter of the DAV, which meets monthly at the Maine Veterans Home, Cony Road.

Betty Adams — 621-5631

Twitter: @betadams

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.