Restricted from owning power plants since a 2000 law restructured the industry, Central Maine Power Co. and Emera Maine would like to get back in the generation business, a move that the companies and their supporters say could lower Maine electricity prices.

Skeptics disagree, saying that prices are just as likely to go higher, and that there’s already enough competition to sell power in Maine, which has the lowest electricity prices in New England.

Both points of view will be presented Thursday to the Legislature’s Energy, Utilities and Technology Committee when it holds a public hearing on a bill that would enable CMP and Emera to generate power, probably through affiliates of their multinational parent companies.

The new generators probably would take the form of wind farms and large-scale solar arrays, and possibly natural-gas plants, based on government policies and market needs in New England.

A bill presented by Rep. Mark Dion, D-Portland, would allow utilities to own generating sources but aims to limit their financial interest so there’s no incentive for them to favor their affiliated project as a source of power. The bill also would charge the Maine Public Utilities Commission with adopting rules to protect ratepayer interests.

Dion’s bill is a different take on a proposed law introduced last year on behalf of Gov. Paul LePage that was carried over to this legislative session. It charges the PUC with determining whether ownership of a generation project would benefit Maine ratepayers.

Much has changed in the industry since Maine’s electric utility restructuring law was passed 16 years ago, said John Carroll, a spokesman for CMP, now a subsidiary of utility giant Avangrid. The original intent of the law was to protect ratepayers from poor investment decisions and give them the benefit of competitive market prices. But safeguards now in place on the federal and regional levels make the law outdated, Carroll said, and no longer helpful for customers.

LePage supports this thinking. His energy director, Patrick Woodcock, said Monday that the additional investments would be good for Maine homes and businesses and that added competition could lead to lower, less-volatile rates.

That notion is dismissed by Tony Buxton, a lawyer representing large businesses in the Industrial Energy Consumer Group.

Maine’s power-supply market has plenty of competition, Buxton said, which has meant lower overall electricity rates. They could be lower still, he said, but for the undersized pipeline network that squeezes the supply of natural gas to New England power plants in winter. Buxton also noted that CMP and Emera Maine’s parent companies already can invest in Maine generators, just not in their service territories, where they are granted a monopoly on distributing power.

Maine lawmakers took up restructuring in 1998. Rates were rising then, in part to cover large power plant investments and to pay off above-market, renewable-energy power contracts ordered by regulators. The idea behind restructuring was to have private companies assume the risks of building new generation, and to encourage a market in which they would compete against each other.

Twenty-two states had restructured their electric markets by 2000, including every state in the Northeast except Vermont. But a power-supply crisis and the Enron scandal led California to suspend its program in 2001, and other states, notably in the West, followed suit. As energy markets have changed, a national debate is continuing over the effectiveness and impact of utility restructuring.

In Maine, LePage has called restructuring a failure. In an interview last spring with the Maine Public Broadcasting Network, he charged that the law has made power costs go up “by huge amounts each year.”

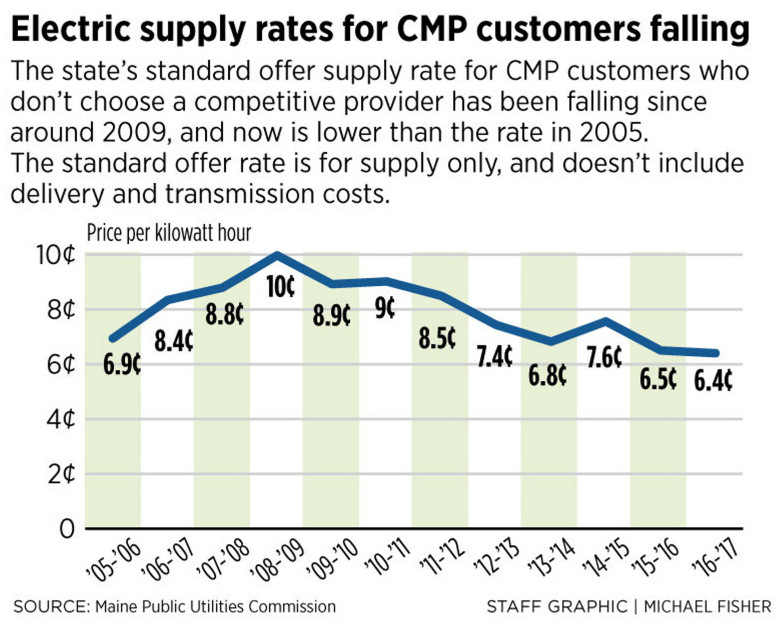

That statement is incorrect. A review of the state’s standard-offer electric supply rates – the default rate paid by home and small-business customers who don’t buy their electricity from a competitive provider – shows that the rate locked in for 2016 is lower than it was in 2005. The standard offer rate increased from 6.9 cents per kilowatt hour in 2005 to a peak of 10 cents in 2009. Except for a bump in 2014, it has fallen since, a trend that experts attribute to the ebb of wholesale natural gas and oil prices.

When distribution charges are added in, Mainers were spending an average of 14.9 cents a kilowatt hour for delivered electricity in 2015, the lowest of any New England state. The price in Vermont, which did not restructure, was 17.4 cents.

Woodcock acknowledged that there’s no way to know whether rates would have been higher or lower over the past 15 years if utilities had continued to own generation. But he said ratepayers are likely to benefit if CMP and Emera Maine’s parent companies invest, because they are long-term owners that could offer more stable rates over time.

Allison Gray, communications and marketing manager for Emera Maine, said Monday that clarifying the law could eliminate unnecessary litigation and associated costs, and that regulatory certainty is important to any business.

“A company looking to invest in Maine needs to know that investment is welcome,” she said.

At Avangrid, CMP’s new parent, Carroll noted that one of the company’s subsidiaries, Iberdrola Renewables, is a major wind and solar developer in the United States, and its expertise could benefit both Maine ratepayers and the environment.

But Buxton noted that Maine already is the regional leader in wind power and, overall, exports roughly as much power as it uses. Risking higher rates by allowing utilities back into generation in their service areas is unnecessary, he said.

At Maine’s Public Advocate’s Office, which represents utility customers, Tim Schneider believes lawmakers and the PUC can impose sufficient safeguards to lower that risk. He agreed that the current federal rules and interconnection procedures by the region’s grid operator weren’t in place in 2000.

Schneider said there’s no way to tell if Mainers would have been better off without restructuring, but that the more narrow issue of how to let utilities own a new fleet of power generators without harming ratepayers can and should be worked out.

“Our thought is (that) having a more competitive market is better than not having one,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.