On David Calder’s first day on the Kennebec River log drive in 1966, he and others were charged with clearing logs from behind the Abanaki Mill, the lower pulp mill at Madison Paper Co.

“We crawled down over this bark pile down to the river, and the river is quite quick there,” Calder, 66, of Canaan, remembered this week. “We took a boat across the river, and there was probably 100 cord of wood jammed into the ledges in high water. All day we hauled wood from that huge pile of pulp to the river and throwing it in, and that’s all we did for days on end.

“At the end of the day, I had all I could do to get up over that bank, and there was this old fella, Ernest Cramer, he reached down and grabbed me, pulled me up over the bank and said, ‘There, young fella, … you’ll eat your beans and johnnycake tonight, won’t ya.'”

Calder was sold on a profession he loved.

But a decade after that — 40 years ago this spring — the centuries-old Maine tradition came to an end, the result of Mainers and the rest of America’s changing views on water pollution, recreation, paper making and highway transportation.

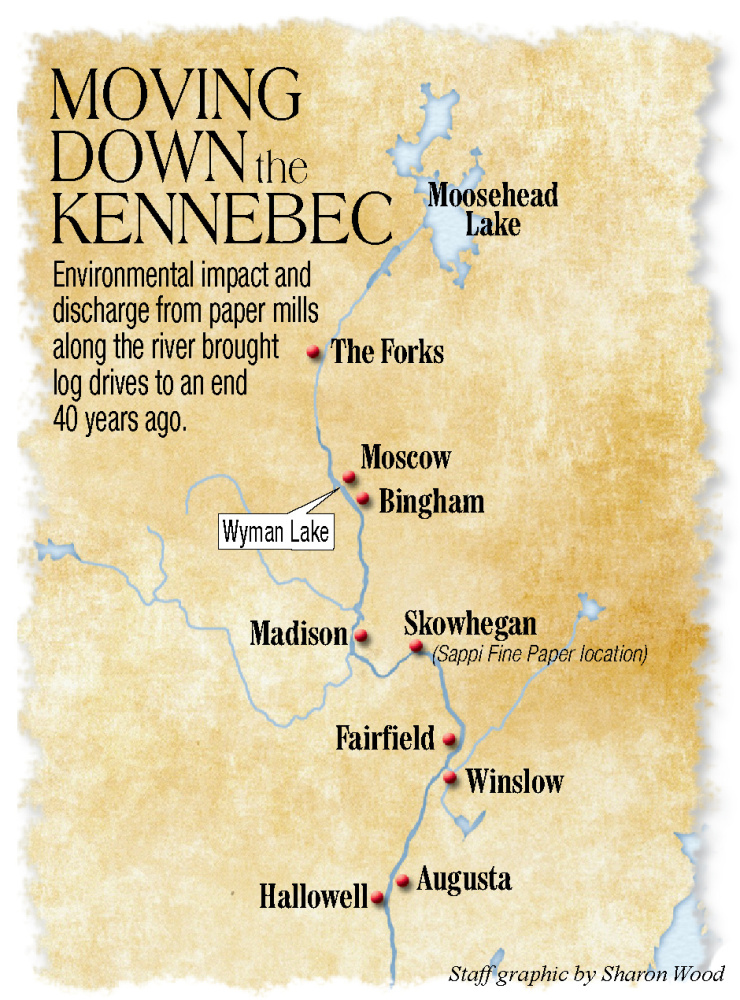

In 1976, change that had been coming for years finally arrived. That was the year of the last log drive down the Kennebec River from Moosehead Lake to The Forks, then all the way to the paper mill in Winslow and finally to Augusta and Hallowell.

“I didn’t want it to end, because I liked the job,” Calder said last week. “I liked being outdoors. I liked being on the river. I liked everything about it.”

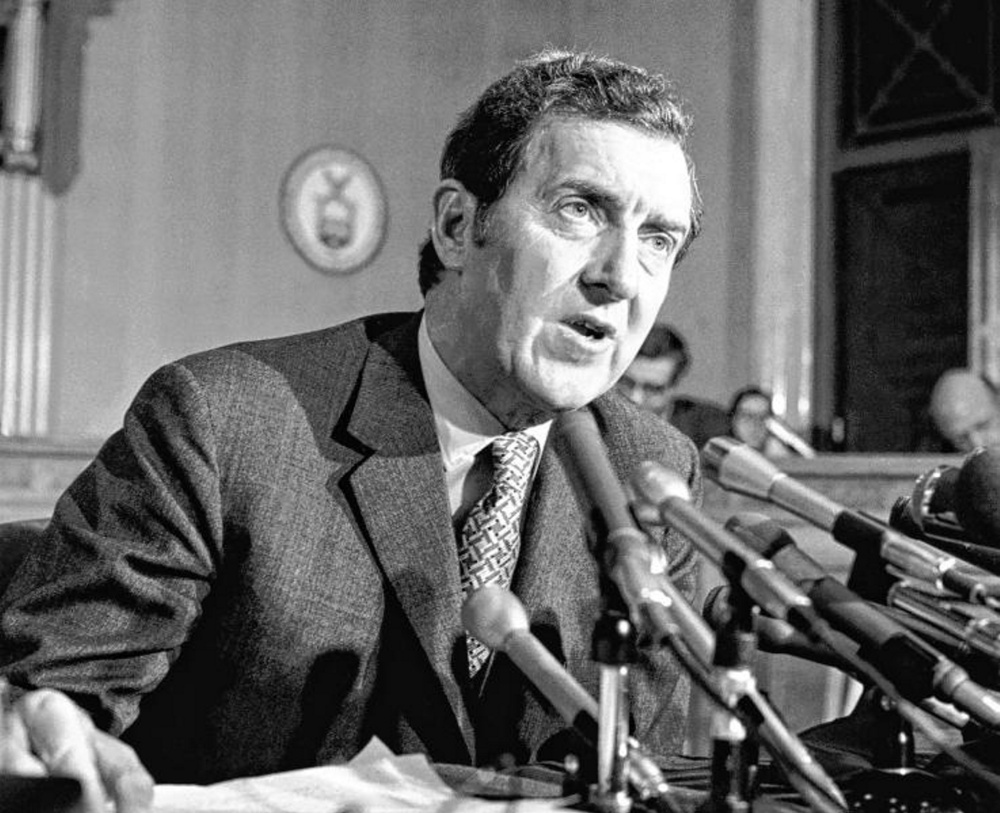

MUSKIE’S ACT

That year, a modern new paper mill off U.S. Route 201 in Skowhegan, where pulp wood could be delivered by truck, was being built by Scott Paper Co. and would be completed a year later, a direct result of the federal Clean Water Act of 1972, ushered into law by U.S. Sen. Edmund Muskie, and a Maine law that banned log driving by Oct. 31, 1976.

The new Skowhegan paper mill, now Sappi Fine Paper, brought development, new homes, property taxes and jobs to the region.

Muskie, from Rumford, another mill town, knew what the mills added to the economy, but deplored what they did to the rivers.

The environmental impact and the discharges from the paper mills along the river brought the log drives to an end. Bark from the logs that settled on the river bottom caused pollution and killed fish. Logs in the river disrupted boaters, fishermen and canoeists.

Up until the pollution abatement efforts of the 1970s, the river was “described as an ‘open sewer,'” David Michor wrote in a 2003 study on the environmental history of the Kennebec.

Those efforts “improved water quality … to conditions that provide for thriving aquatic life and improved access, enjoyment and economic health … vibrant commercial districts appeared, and tourism, fishing, boating and swimming all increased as a result of the improved river quality,”

Maine’s rivers are cleaner and Maine’s highways are safer and stronger, those with expertise in those areas agreed last week.

And at the helm of the environmental movement was Muskie.

“Before Ed Muskie, there was no national environmental policy,” Leon G. Billings, president of the Edmund S. Muskie Foundation in Bethany Beach, Delaware, writes on the foundation’s website. “There was no national environmental movement. There was no national environmental consciousness.”

Muskie was a state legislator and Maine governor before being elected to the U.S. Senate in 1959. He was secretary of state under President Jimmy Carter and was the Democratic nominee for vice president in the 1968 presidential election and a candidate for the Democratic Party nomination for president in 1972.

He had the nickname Mr. Clean.

In correspondence this past week, Billings said the Clean Water Act and a bill in the Maine Legislature banning river log drives were “clearly a part of the long range view of Muskie and clean water.”

He said Muskie first raised the water quality issue when he was a candidate for Maine governor in 1954 and in his State of the State speech, and later it became an issue in his campaign for re-election.

Billings said Muskie was an avid fisherman and concerned about what the paper companies were doing to Maine rivers.

“Whether or not he had a direct connection with the log drive bill, or it was just another of the many spawn of his leadership on clean water, I am uncertain,” Billings said in an email this week to the Morning Sentinel. “I am certain, however, that without his leadership on environment and pollution, most of these kinds of laws would not have been priorities anywhere in America.”

THE LOG DRIVE

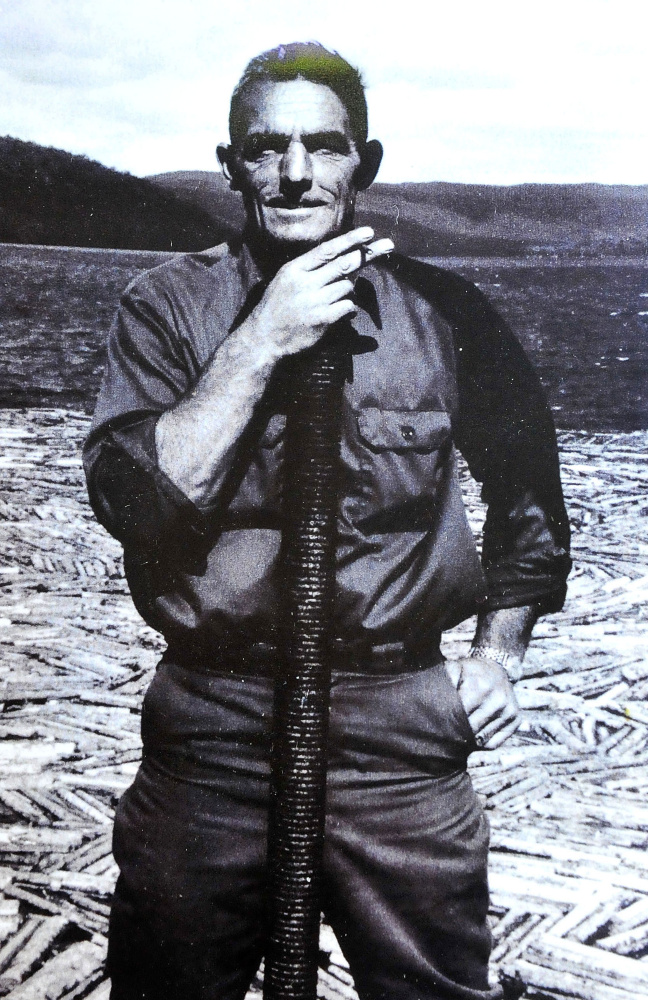

The last log drive ended a way of life for Calder, who’d started as a 16-year-old growing up in Skowhegan.

“In the spring of the year when we were hanging the booms, there was five or six of us on a crew,” Calder said.

Hanging the booms involved using long logs linked with chains to form a channel. Piers pointed thousands of cords of fir and spruce logs, cut in four-foot lengths, to sluice ways at dams along the Kennebec.

Some of the permanent piers can still be seen in the river from Fairfield to Gardiner. Calder said he and other would be sluicing — diverting the logs through a gate and over a dam — during the summer.

“Then in the fall, when we took up the rear, there would be 25 or 30 guys — 10 or 12 on both sides of the river, plus the guys in the boat,” he said.

Taking up the rear meant hauling logs that had drifted or got jammed on the shore and dragging or tossing them back into the river.

Calder said the river drive logs came from the Moosehead Lake region and from many of the small towns along the route of the Kennebec. Logs were driven into small streams that fed the river or were rafted by tugboat across large bodies of water, including Wyman Lake at Moscow and Bingham, and sluiced back into the river. Logs were sluiced at nine dams, including Madison, Skowhegan and Shawmut in Fairfield, down to the Scott mill in Winslow.

Logs were off-loaded to be milled in Winslow, and more continued down the river to Augusta.

“It was labor intensive, but the river did most of the work,” Calder said, noting that when he started the log drives on the Kennebec in 1966, he made $1 an hour working for the Kennebec Log Driving Co. of Skowhegan. Buster Violette was the drive foreman.

Calder, his father, Ed, and many other men from the area worked on the drives from the first week of April straight through to Thanksgiving. Their work on the Kennebec is seen in a video “The Last Log Drive” by the Maine Public Broadcasting Network.

The volume of logs coming down the river through the Skowhegan Gorge during a drive could number anywhere from 400,000 to 500,000 cords of pulp wood destined for the paper mills, Calder said.

A NEW ROAD

Roads were carved all over the Maine woods for trucks and machinery to do the work that streams, rivers and men had done for 200 years.

The Golden Road, a privately owned and mostly unpaved road that runs from Millinocket to the Quebec border, was built as a direct response to the end of the log drives down Maine rivers. Trucks and new roads changed the way wood was harvested and changed the scale of the volume of wood taken to mills, said Fred Michaud, a policy development specialist at the Maine Department of Transportation.

Michaud said wood was hauled primarily by water particularly in the North Maine Woods in the years before the log drives ended.

“Woods operations not having easy access to waterways and lakes trucked their product, but the pulp trucks of yore were the size of a wheeler dump truck and not the 100,000-pound trailer trucks used today,” he said. “One only has to compare a late 1970s DeLorme atlas with one of today to realize that roads have been built nearly everywhere to access the forest product. Again, one can infer that that increase has a corresponding increase in the number of trucks.”

Michaud said what used to be an army of workers working in the woods without a lot of trucking became a handful of machines doing most of the work. With more trucking came new and better ways to build roads, such as U.S. Route 201, which runs along the Kennebec River from The Forks to Augusta.

“That arterial type highway has been upgraded and improved to a standard to take 100,000 pounds of trucking and that volume of trucking,” Michaud said. “We looked at our heavy hauling network over the last 50 years in this state, and we have improved our highways to accommodate that major shift of production and harvesting of the forest from the water-based delivery system to a highway-based one, and they’ve stood the test of time.”

Michaud said the state gasoline tax helps pay for the continued upkeep of Maine’s roads and bridges, as do transportation bonds that are approved by voters for road infrastructure, but it’s never enough to keep up. The state’s Land Use Planning Commission also has standards for roads in rural territories along with erosion control.

He said the state’s highway system is safer than it was 40 years ago with new paving materials and methods and do not have to be revisited every few years for repairs.

‘YOU JUST GO ON’

The story of the end of the log drive has to include environmentalist Howard Trotsky, Calder said.

As a University of Maine aquatic biology graduate student in 1968, Trotsky studied trout in the Kennebec just below Wyman Dam, according to a 2003 University of Maine master’s thesis on the Kennebec River by Daniel Mitroch provided by the Muskie Foundation.

Trotsky noticed significant trout population declines and attributed it to the log drives and associated bark deposits. He used his riparian rights to initiate legal action against the largest contributor to the log drive, Scott Paper Co.

Despite being called a radical conservationist, Trotsky gained significant public support when he sued the company in November 1970 to have the logs removed. His case rested on the fact that he had the right to take his boat down river without hazard to navigation, according to the Mitroch thesis and historical archives.

The accumulation of sunken pulpwood logs affected water quality and the physical structure of the habitat, and it introduced bark and wood fibers to the sediment, greatly lowering available oxygen for aquatic life, Trotsky held.

In response to public opinion and the pending court case, the state of Maine passed an act in 1971 prohibiting log drives. In addition, log drives did not comply with the Clean Water Act because of the pollution the logs caused to the river. The company appealed the case two years later, but lost.

Efforts to reach Trotsky, who still is listed as living in Caratunk, were unsuccessful.

Calder, who had worked the Kennebec River log drive for 10 years, knew the drive of ’76 would be his last.

With his wife, Maureen, he raised three children. He worked construction after his riverdriver career ended, then briefly was a substitute school teacher until he retired.

At the close of the log drive in 1976, the boom chains were collected and sold as scrap, Calder said.

The river is cleaner now, he said, not only because the drives ended, but the paper mills are dumping fewer chemicals and there has been a cleanup of municipal solid waste going directly into the river.

Calder liked the job and didn’t want it to end.

“We knew,” he said. “Everybody’s life is full of disruption. You just go on, that’s all.”

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

Twitter:@Doug_Harlow

Copy the Story Link

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.