“With some notable exceptions,” said scholar Gary Wolfe, “science fiction has seldom been a widely popular literature. … It has only occasionally broken onto the best-seller lists in a way that romance novels or horror novels do on a fairly regular basis.”

In fact, it happens so occasionally that it didn’t occur to Alex Irvine — or apparently even his agent — to keep tabs on The New York Times best-seller list after the publication of his novelization of Guillermo del Toro’s film “Pacific Rim” in 2013. Just this month it accidentally came to Irvine’s attention that the book hit No. 19 on the Times’ Paperback Mass-Market Fiction list for Aug. 11, 2013.

It’s hard to imagine how you could be as prolific a writer as Alex Irvine is, yet assume you’d be a UFO on The New York Times’ radar. Irvine’s situation might tell the story of professor Wolfe’s literary world in a nutshell.

For the past few years, Irvine has been soaring through this literary separate reality. His “in-world fictionalized companion” to the video game “The Division: New York Collapse,” published this spring, has been on Washington Post best-seller lists the last few weeks. “Batman: Arkham Knight — The Riddler’s Gambit,” a “prequel” novel tied in to the video game, appeared last June; and this June his novelization of the “Independence Day” movie sequel, “Independence Day: Resurgence,” is scheduled for publication.

He’s writing the “Marvel Avengers Alliance” video game story and “a bunch of new short stories,” he said this month in an email, and is completing a novel he’s been “working on, off and on, since 2002.”

Since 2002, hmm. In Irvine space-time, that spans five original novels (including “Buyout” in 2009), several comic book stories, several film and game tie-in books, three collections of short fiction, a slew of stories in chapbooks and magazines, a bunch of essays on science fiction and fantasy, and a stint teaching creative writing at the University of Maine in Orono. At present he is living in South Portland.

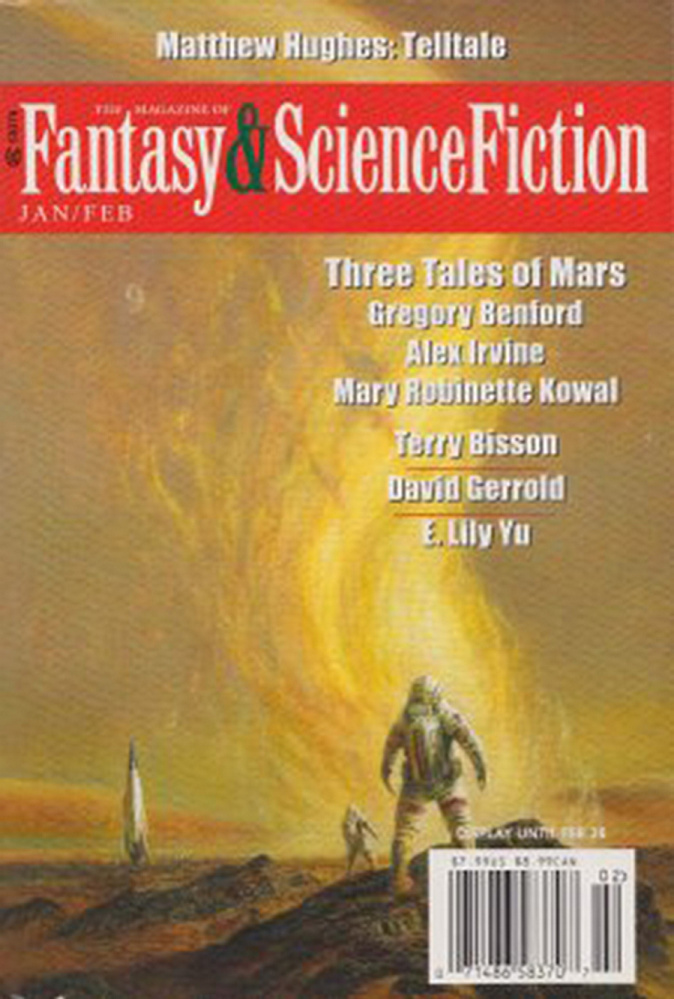

This winter his story “Number Nine Moon” appeared in the January issue of the eminent Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, where his stories appear fairly often. It’s a funny imagination of the last few settlers to vacate Mars after a discombobulated effort to colonize the place, a happy reminder (to me, at least) of how brightly and cleverly his prose skates along, a literary cut (and more) above much of what you read in the genre.

His stories usually focus on average Joes who find themselves in bizarre situations, ranging from working-class Detroit residents caught up in a plot to wage World War II with an army of supernatural golems (in “The Narrows”) to what the “virtual” in virtual reality really means, a theme explored in some of his short stories.

“For All of Us Down Here” (Fantasy & Science Fiction, January 2014) depicts life in Orono after the Singularity, when everybody cool has uploaded themselves into “the Sing.” Down here, everything’s been gutted, but at least it’s got substance. Where would you rather live — nowhere safe, or somewhere gray? In “Watching the Cow” (F&SF, January 2013), a computer programmer in 2022 “was working on a way to harvest full motion-capture profiles for users of VR goggles. She wrote some code. … She ran the test. Two million kids went blind.” And in “Shambhala” (F&SF, March 2006), some programmers in “the Great Brain of Meatspace” inadvertently cause creepy disruptions for “Virt” avatars.

“(Artificial intelligence) will keep advancing,” Irvine wrote when asked about it, “but we seem really convinced that we can model AIs on us and then avoid having them act like us. Do we really want nearly omnipotent artificial intelligences with us as a template?”

Welcome to Irvine concision-irony.

All this Irvinalia is flying boisterously along mostly off the mainstream radars, but in the thick of the SF-fantasy-speculative fiction radar. By now, is science fiction still a literary reality separate from “literature”?

According to Wolfe, the answer is yes and no. “Science fiction is no longer uniformly regarded by the literary world as an embarrassment or a subliterary genre,” he says in his course “How Great Science Fiction Works.” But at the same time, there’s still a tendency among, let’s say, the Times’ high-end readership to pay little attention.

Irvine’s thoughts: “You look on a shelf of science fiction now, and along with (Isaac) Asimov and (Arthur C.) Clarke and (Ray) Bradbury you see (Sofia) Samatar and (Cixin) Liu and (Nnedi) Okorafor and (Hamayun) Ahmed and (Vandana) Singh. The field is immensely richer for this. … Science fiction is better than it’s ever been right now.” And for good measure, he offered the examples of Maine-based writers Elizabeth Hand and Catherynne Valente.

Both the creators and the audience are much broader than they were 50 years ago. “The writing,” as we used to call that intangible sense of richness and quality (or lack thereof) that arises out of words, has improved to meet the interests and requirements of a diversifying set of radars. The prodigious production of Alex Irvine and others is making its way out of UFO territory.

Alex Irvine’s books and stories are available through his website alexirvine.blogspot.com.

Off Radar takes note of books with Maine connections every other week. Contact Dana Wilde at universe@dwildepress.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story