WINSLOW — When Cory Dow and his young family moved into their newly built home last winter on Clinton Avenue, they noticed that the water from the well that had been drilled in 2014 tasted strange. Dow initially chalked it up to variations in well water and didn’t think much of it, but it kept getting worse.

“It was the end of March when I realized it was really awful. It tasted like ocean, like salt water,” Dow said.

When he had the water tested, the reason for the foul taste was immediately apparent. The level of sodium and chloride — salt — was off the charts, more than 20 times above drinking water standards. Dow eventually shut off his well and spent about $10,000 to connect to a public water line after he started seeing salt buildup on his furnace and worried it would corrode his plumbing.

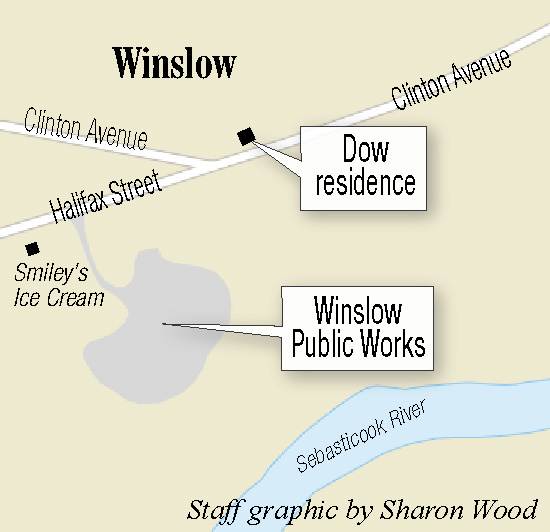

Dow believes the source of the contamination is the uncovered pile of road salt at the Winslow Public Works garage, less than a tenth of a mile down the road from his house.

His suspicion was confirmed by a January report from the Maine Department of Environmental Protection that concluded Dow’s well pollution is the result of salt water flowing into the well from cracks in the bedrock under the salt pile.

But the town, in its own report released last summer, denied responsibility for the contamination and refused to compensate Dow for the cost of his public water connection. Instead, it theorized the contamination could be caused only by someone deliberately pouring salt into the open well, although it did not explain why someone would have done that.

“Someone is responsible for your unfortunate situation, but it is not the town of Winslow,” town attorney Bill Lee wrote in a July 15 letter to Dow.

After being confronted with the DEP’s findings, the town now appears willing to negotiate a settlement. According to Town Manager Michael Heavener, the town attorney has been in contact with Dow’s lawyer to discuss the problem.

At least one of Dow’s neighbors also is considering filing a complaint with the town about contaminated well water, but town officials and Peter Garrett, the geologist who wrote the initial report for the town, still aren’t convinced the municipal salt pile is to blame.

“The fact of the matter is, nobody knows for sure,” Heavener said.

“Unless you go down there and look, you don’t know what is going on subsurface. (Garrett) speculated based on his experience and DEP speculated based on their experience,” Heavener said.

A POISONED WELL?

In a water test last April, Dow’s well water measured 2,800 milligrams of sodium per liter, 28 times the limit a healthy person should ingest. The level of chloride was 6,200 milligrams per liter, almost 25 percent the secondary drinking water standard. The May results were slightly lower but still far beyond safe standards, 2,600 milligrams per liter of sodium and 4,700 milligrams per liter of chloride.

According to the Maine Center for Disease Control, chloride has no negative health effects, but it can give water a salty taste and corrode pipes, pumps and plumbing.

Ingesting too much sodium, on the other hand, can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and high blood pressure. The water standard for sodium in drinking water is 20 milligrams per liter, and for most healthy people, 100 milligrams per liter will not substantially increase health risks, according to the center.

Dow suspected the salt pile, which is about 1,000 feet away from his home on the other side of Clinton Avenue, was to blame for the contamination. His suspicion grew after he learned his neighbor, Caleb Albert, also was having problems with his well water.

Uncovered piles of road salt and sand leach into groundwater, and runoff from road treatment can affect private wells. Salt contamination is a big enough problem that Maine’s departments of transportation and environmental protection have a specific program to field complaints, assist local governments with paying for salt and sand piles, and finding locations for new piles and buildings. The state has a priority list of salt piles that should be covered because of the risk they pose.

In June, Dow filed a formal complaint with the town, stating his concern and asking for compensation. State law gives people the right to petition their local government to determine the cause and assess damages when they believe their private water source has been polluted by local government action.

“I believe the town — now that I don’t have a private well — should be paying for my water as long as I live in that house,” Dow said.

Dow had the option of hooking up to public water when his house was built — the town was connecting people in the area at the time — but he declined.

He was surprised when the town turned down his claim and denied responsibility. The rejection was based on Garrett’s report, filed a week after Dow made his complaint.

Garrett acknowledged the salt pile probably was leeching into the groundwater, but since it is 850 feet from a steep bank into the Sebasticook River, salt runoff should flow toward the river, not in the other direction, to Dow’s well, Garrett said. Garrett added that a contact at the Department of Transportation told him chloride levels in wells contaminated by salt piles are typically about half of those recorded in Dow’s well, further proving the salt pile couldn’t be the problem.

Instead, Garrett concluded in his report to the town that “the most likely cause of contamination of the Dow well by salt was deliberate contamination, by pouring a bag of salt down the open casing after removing the unlocked well cap.” That would keep high salt concentrations in the area below the pump that would remain unless it was flushed by pumping for a month to remove the salt, Garrett wrote.

Garrett said last week he stood behind his report, but he could not explain why someone would put salt into Dow’s well.

“It happens occasionally. It is not common,” Garrett said.

Dow can’t imagine why someone would go to the effort to pour salt into his well. “There is absolutely no reason for that,” he said.

SALTING THE EARTH

After the town rejected his application, Dow took his complaint to the state Department of Environmental Protection.

After months of intermittent investigations by a joint team from DEP and Maine Geological Survey, the department released a report in January, theorizing that the cause of the contamination was probably a flow of “dense salty brine which had been trapped deep in the bedrock fractures.”

“If this is the case, it is believed that the primary source for the salt would be the Winslow salt pile,” state investigators concluded.

Although the salt pile is next to the Sebasticook River, the dense salt water from the pile will dive deep into the bedrock and sink to the bottom of the groundwater instead of flowing across the surface and into the river, said Mark Holden, an environmental specialist with the DEP.

“Logically, because it is so close to the river, you would think it wouldn’t be a problem,” Holden said last week. “But groundwater and physics behave in funny ways.”

According to the DEP analysis, the sequestered saltwater is trapped below the level of the river and eventually will make its way into the waterway. But when Dow started pumping water, the forced flow was strong enough to pull the saltwater from the rock fractures into the well, Holden said. The main fracture lined up with Dow’s well, he said.

The department based its finding by testing groundwater for electrical conductivity — saltwater conducts electricity better than regular groundwater, Holden said. The tests showed low conductivity on the Sebasticook River bank, but high conductivity in Dow’s well that increased the deeper the tests were taken, according to the DEP report.

It’s uncommon for the DEP to investigate specific cases such as Dow’s, which is why it took months to compile the report, Holden said. He and a group of other scientists from DEP and the Maine Geologic Survey found time in their schedules to compile readings and analyze the findings.

The department’s interest in the case was sparked by Garrett’s conclusion that the well was contaminated intentionally, Holden said.

If that was the cause, the person would have had to poison the well after it had been drilled, but before the pump was put in, Holden said. It would have had to have been done during the 2014-15 winter, when there was extreme cold and heavy snow, which would have made access to the well head difficult.

“Then you have to ask, ‘Why would anyone want to do something like that?'” Holden said. “It just didn’t make sense to us, logically.”

In defending his conclusions, Garrett says that the DEP had measured only 250 feet into the 325-foot well and hadn’t pulled the pump out to check it. As far as he is concerned, the investigation isn’t over.

“I came to a conclusion. DEP came to a different conclusion. They did a certain amount of work. There is a little more work they didn’t do that would show one way or another,” Garrett said.

When told about Garrett’s response, Holden said he would consider studying the issue further if the town is willing to pay for it, but the department doesn’t have a budget to hire a contractor to extract the pump.

The conclusions reached in the report are still only a hypothesis, he said.

“We can’t say we know that we are right. We only can say we think logically that what happened is that you had sequestered salt; it didn’t go directly into the river,” Holden said. “Based on the measurements we did, it seems to add up.”

MORE COMPLAINTS

While Dow’s case is still pending, at least one other resident whose wells possibly have been contaminated by the town salt pile is considering filing for compensation for the town.

Caleb Albert, who owns three homes across the road from Dow’s property, said he suspected something was wrong with his well water three years ago. The three houses are just north of the salt pile, on the same side of Clinton Avenue.

“When I was trying to grow grass at one of my houses, I kept watering it and nothing would grow. I couldn’t figure it out,” Albert said. “I stopped watering it, and two weeks later I had a lawn. It’s kind of hard for grass to grow when you water it with salt.”

According to water tests last May and June, all three of Albert’s wells were over the 20 milligrams of sodium per liter threshold. The house he lives in measured 170 milligrams per liter, according to Garrett’s report.

“At first, I thought I had hard water; but over the past year, year and a half, it has gotten considerably worse,” Albert said. He doesn’t drink the water in his house, or use it for cooking, and is considering connecting to public water as well but estimates it will cost $11,000 to $12,000. He’s planning to file a complaint with the town for compensation.

“I’ve already paid for water once. Why should I pay for it again?” Albert said.

Both Dow and Albert say what they really want is for the town to own up to the contamination and cover the salt pile.

According to the DEP report, Winslow’s salt and sand pile was exempted from a DEP rule that requires covered salt storage because it was listed on the lowest priority by the state and was not within 300 feet of a private well.

If the DEP’s findings about the Dow well contamination are correct, runoff from the salt pile appears to have infiltrated the groundwater for the approximately 50 years it has been at the site.

Since the town can’t extract the salt from the bedrock, it should at least cover the pile to prevent future pollution, Albert said. He doesn’t understand why the town is permitted to discharge saltwater into the Sebasticook River.

“If a homeowner was to have done something like that, the DEP would have been all over them. Why does (the town) get to get away with it?” Dow asked.

“They have to do something, because if any one of the wells in the area aren’t affected now, in 10 years they could be,” he added.

Heavener said he isn’t sure why the town didn’t apply for state money to build a shed to cover the pile, but there are no plans to do so now.

The town’s insurance doesn’t cover well contamination, so any settlement with Dow would have to be paid with town money, something the Town Council would have to decide. Heavener, who was Winslow’s police chief for six years before becoming town manager, said he’s still not convinced Garrett’s conclusion of deliberate contamination is incorrect.

“From my law enforcement experience, I have seen that happen. It is something you certainly can’t rule out,” Heavener said. “It would certainly appear that any runoff from the sand and salt pile would run down to the river. Water tends to run downhill and follow the terrain.”

Dow said the entire experience has been frustrating. He is disappointed in what he regards as the town trying to dodge responsibility for its mistake. The well he drilled for his new home is unusable — it will take decades to clear salt from the groundwater, he said — and he is out of pocket for connecting to the public system.

“My frustration is that I feel the town is not protecting its citizens from this,” Dow said. “They are trying to deny liability, which is unfair.”

Peter McGuire — 861-9239

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.