OAKLAND — For 21 years Angela and Edwin Mullen didn’t give up hope that their son Aaron might one day wake up from a coma and fulfill his dream of becoming a Maine State Police trooper.

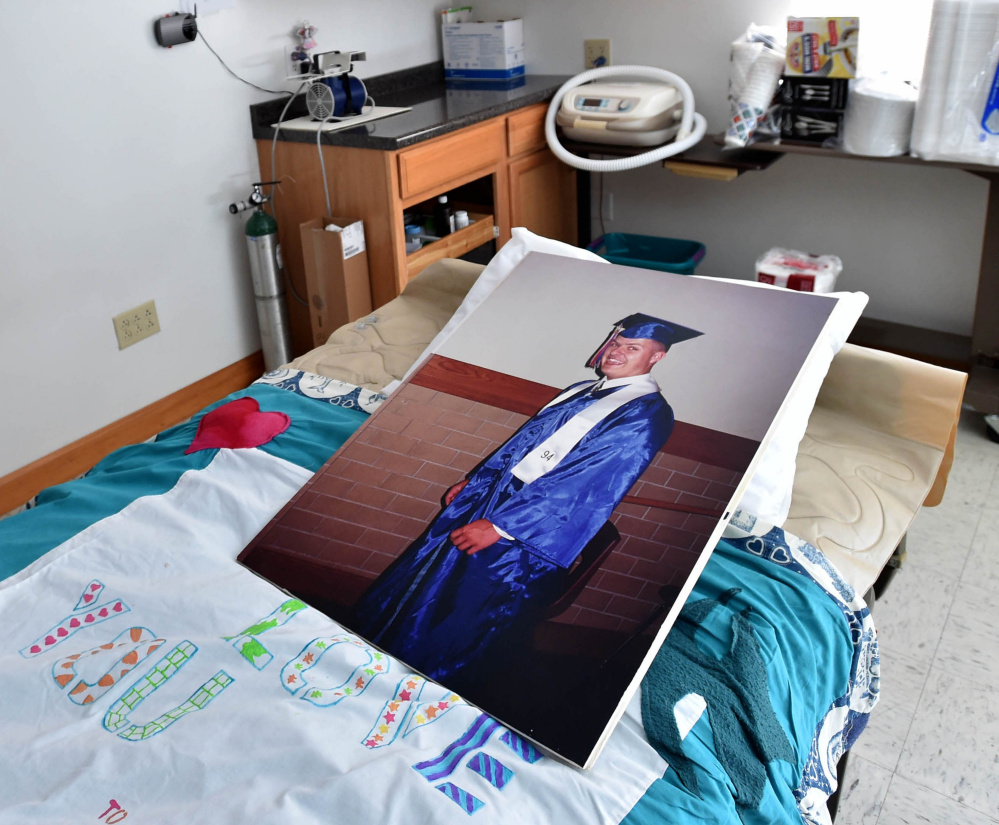

They took turns caring for him 24 hours a day, communicated with him as best they could, and even built an addition to their house to accommodate his medical needs, filling it with family photos, mementos and a handmade quilt embroidered with “We love you” to cover his bed.

Their dream came to an end April 9 when Aaron Mullen, 40, died after spending more than two decades in a coma.

His family believes that if not for the gunshot wound that pierced the side of his face in October 1994, he would be with them today.

“Aaron never had a life,” said his mother, Angela, 69. “His life was taken from him the day he was shot. He was given a life sentence in his home.”

The Office of the Maine Attorney General will not press murder charges against Jason Poulliot, who was 16 when he shot Mullen.

Poulliot, now 37, served 10 years in prison on attempted murder charges and was released in 2007. When reached Friday, he said he did not want to comment for this story, but his wife, Katie Poulliot, said that the family “extends our deepest sympathies to the Mullen family — we are truly sorry for their loss.”

The Department of Corrections said last week that Poulliot hasn’t shown back up in the state prison system, and aside from a few civil violations — he pleaded guilty to cultivating marijuana in 2010 and was also convicted of a fishing violation in 2011, according to court records — has stayed out of the news.

Mullen had no insurance at the time of the accident, and his medical care has been paid for in part by MaineCare. The Morning Sentinel reported in 1999 that the community rallied around the family after the shooting, holding fundraisers and taking up collections, but that dropped off as the years went on.

Because of cuts to state programs, the family has had to pay for and even provide some care themselves. Along with a team of nurses, they made sure he was turned over in bed, brushed his teeth and washed his hair and put him in a wheelchair to take him outside.

He couldn’t walk or talk, but communicated in small ways, with his eyes or a smile, and he was capable of small movements like the thumbs up he often gave to family members to show he was happy.

‘TRYING TO INTERVENE’

Mullen’s family describes the youngest of four children as full of life.

After he graduated from Messalonskee High School in 1994, he had plans to study criminal justice at the University of Maine at Augusta and become a Maine State Police trooper. His pride and joy was a bright red 1974 Chevy Nova that his family still has in the garage.

“He was always fun, always full of spunk,” said Mullen’s sister, Tammy Phillips. “He was a happy-go-lucky kid.”

Mullen once tracked down a shoplifter from Al Corey’s Music Center in Waterville on foot. He enjoyed going on ride-alongs with Waterville and Oakland police.

His family believes he was trying to intervene and prevent a crime the night he was shot on Route 23 in Oakland.

“He always wanted to be a state trooper, and that’s what he was doing that night, trying to intervene before the police got there,” said Edwin Mullen, 72.

According to police and witness accounts, Mullen, a 19-year-old gas station attendant at J&S Oil on Kennedy Memorial Drive, was flagged down by his cousin and some friends on his way home from work the night of Oct. 30, 1994.

The teens told him they had been involved in a dispute with a rival group from Fairfield, and that they’d just called the police.

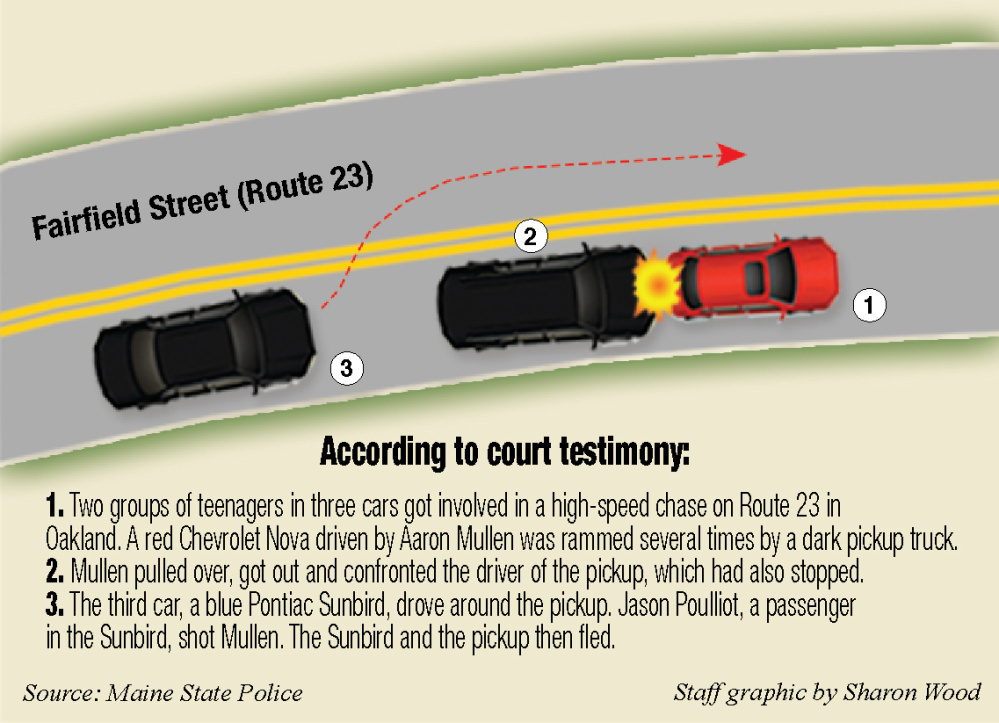

Thinking a police cruiser was on the way, Mullen spotted the two vehicles — a dark pickup truck and a blue Pontiac Sunbird — on Oak Street in Oakland and drove ahead of them to get them to stop. The driver of the truck rammed Mullen’s Nova on Fairfield Street, and he got out of the car to confront the driver.

The Sunbird then drove around the pickup truck, and Poulliot, a passenger, shot Mullen in the head with a .30-30-caliber hunting rifle.

“The barrel was right in his face,” a witness told a Lincoln County jury in October 1996. “They weren’t even a foot away from him”

The bullet entered Mullen’s temple and exited near his mouth. It didn’t penetrate his brain, but police said the shock wave of the bullet interrupted his brain activity, causing him to go into cardiac arrest and suffer seizures.

Poulliot testified in court that he had intended to shoot out the tires of Mullen’s car but that the gun “just went off,” the Morning Sentinel reported.

Doctors said Mullen would likely not come out of the coma, but his family never gave up hope. After more than a year in the hospital, they brought Aaron home to Oakland in February 1996, a day that his father called “one of the happiest of my life.”

Since then, Mullen lived mostly at home until his diagnosis with aspiration pneumonia last year, an inflammation of the lungs that occurs when they fill with fluid or other foreign material.

Edwin Mullen’s eyes fill as he talks about his son’s Nova. He said he developed many coping mechanisms for seeing his son in a coma.

After the trial in 1997, he told the Morning Sentinel that he hoped his son would be behind the wheel again some day.

“I start it up every now and then to keep it lubed,” he said in March 1997.

Angela Mullen said her faith — and her son’s smile — helped her get through hard times.

“He kept me going with that smile that said, ‘Thank you, Mom.’ I’m going to miss that. There were some hard times, and sometimes you felt like giving up. People would say, ‘How long are you going to do that?’ and I would say, ‘Until the Lord takes him. That will be my last day.'”

She said she forgives Poulliot, though it has been hard for her to find closure to what happened that night in 1994.

“After 21 and a half years at home, you don’t have closure,” she said. “If Aaron had passed on during the injury it may have been different, but when you care for a loved one for so long, it’s overwhelming. Right now I can’t feel about myself, I’m just feeling for Aaron.”

A doctor at Poulliot’s trial testified that while Mullen wouldn’t likely come out of the coma, he “may live a week or for 20 years.”

TWO TRIALS

Angela Mullen said the state has been in touch with her about her son’s case, but she’s not interested in seeing new charges brought.

Lisa Marchese, criminal division chief for the attorney general’s office, said Thursday the state medical examiner has completed a full autopsy on Mullen, but that “even assuming Mr. Mullen died as a result of the original gunshot wound, the state will not be pressing murder charges against Mr. Poulliot.”

Double jeopardy — the judicial provision that a person can’t be tried twice on the same charge — would not prevent the state from bringing up a murder charge, but Marchese said Poulliot already served a significant sentence “akin to really as if he had been convicted of murder.”

When District Court Judge Jessie B. Gunther ruled in June 1995 that Poulliot would be tried as an adult, she called him “a criminal, not a kid,” and said the seriousness of the crime and Poulliot’s character contributed to her decision.

Poulliot remained expressionless as Gunther issued her ruling, but his mother, Iris Hope Bailey, began to sob, the Morning Sentinel reported.

The case went to trial twice. A Lincoln County jury deadlocked on an attempted murder charge and convicted Poulliot of aggravated assault in November 1996.

William Stokes, then an assistant attorney general, fought to bring the case to trial a second time. In March 1997, in a trial held in Franklin County Superior Court, Poulliot, then 18, was sentenced to 30 years, with all but 20 years suspended, for attempted murder and a concurrent 10 years for the aggravated assault charge. He had already served two and a half years in the Maine Youth Center and the Kennebec County jail — time that was deducted from his prison term.

Poulliot was also ordered to pay about $8,000 toward Mullen’s medical care. The family later filed a civil suit against Poulliot and several others involved in the altercation that night. Angela Mullen would not comment last week on the outcome of the civil suit.

When Poulliot was sentenced, Stokes said he took no pleasure in watching Poulliot being led off to prison. “This is not about winning and losing. This is about human tragedy,” he said at the time.

Poulliot appealed the case in 1999, arguing that the state did not prove an intent to murder Mullen, that his death was an accident, that trying him a second time constituted double jeopardy and that he should have not been tried as an adult.

The Maine Supreme Judicial Court rejected the appeal.

‘NO REASON AT ALL’

Poulliot was released Aug. 3, 2007, from the Maine State Prison in Warren. His probation ended Jan. 5, 2015.

The 37-year-old now lives in Albion with his wife and children, and he declined to comment for this article.

“Everybody makes mistakes. Jason was just a teenager at the time of the shooting, and he truly is remorseful, but the past cannot be changed,” Katie Poulliot told the Morning Sentinel. “All I can say is that for as long as I’ve known him, he has been a loving and caring husband and father. He’s always been a positive part of my life and my children’s lives.”

When sentenced in 1997, Poulliot, his voice breaking, addressed the courtroom, telling Edwin Mullen he was sorry. Angela Hinck “couldn’t bear” to attend the trials, her husband had told the Morning Sentinel.

“Mr. Mullen, I’m very sorry,” he said. “Everyone says I have a lack of remorse. It’s not right.”

He also said the tragedy should be a lesson for young people contemplating violence.

David Cloutier, Poulliot’s attorney during the two trials in the 1990s, is now an assistant attorney general and did not respond to requests for comment. He said at the time of the trial that Poulliot was remorseful and was trying to turn his life around.

Stokes, now a justice for the Maine Superior Court, declined to comment on the case, citing strict regulations regarding what comments can be made by superior court justices.

“The long and short of it is that Mullen was shot for no reason at all,” wrote Morning Sentinel columnist Gerry Boyle in a column published five days after the shooting on Nov. 4, 1994.

“This is a common occurrence in big cities,” Boyle wrote. “In fact, the same day this newspaper carried news of Mullen’s shooting, the Boston Globe had a page-one story about a 9-year-old killed on his birthday in a drive-by.

“What we have in sleepy Maine is something less organized but just as alarming. We have kids numbed to violence by television and movies, where the bullets fly like sleet,” Boyle wrote.

Now a crime novelist and associate director of communications at Colby College, Boyle on Friday recalled the shooting as having a big impact on the Waterville area, generating an outpouring of sympathy for Mullen and his family in an era where drive-by shootings were unheard of in Maine and guns were just a part of life, not a vehicle for criminal activity.

“People should see what happens when you shoot somebody in the face,” Boyle said. “You know how they bring smokers’ lungs around in a jar when they talk about smoking? You don’t see the after-effects of this kind of thing. We see people lying on the street or hauled away in ambulances, but you don’t see Aaron Mullen 10 years later still hooked up to machines or a respirator day after day after day with people caring for him.”

Today, the Mullen family lives just a few miles up the road in Oakland from where in November three people were shot to death by a man who then killed himself. The Mullen family still feels the effects of gun violence that took place more than 20 years ago.

Standing in her son’s bedroom on a recent afternoon, Angela Mullen thumbed through a photo album of his pictures.

“It’s hard. He’s not here, and just looking at this space is hard,” she said. “We got this big addition for him and now he’s gone. You have to look at that every day.”

Angela Mullen’s last name has been corrected in this story.

Rachel Ohm — 612-2368

Twitter: @rachel_ohm

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.