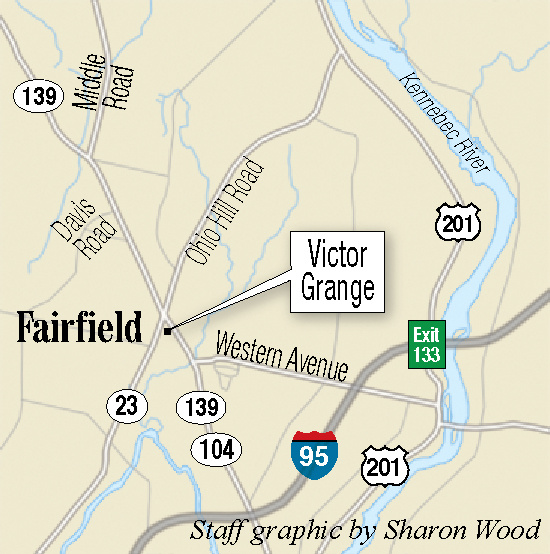

FAIRFIELD — Little brown bats are causing big trouble at the Victor Grange 49 in Fairfield Center.

“There’s bat guano everywhere,” said Grange member Barbara Bailey Monday. “It’s six or eight inches deep in places.”

The guano — excrement from the bats — is eating its way through the Grange hall’s attic and ceiling and flaking down onto the chairs and floor of the second-floor concert hall below.

Bailey said the bats are well established in the Grange hall attic, where a “maternity ward” is visited annually through holes in the hall’s roof and siding, something that’s been going on for perhaps the last 100 years.

Grange members are caught between the need to preserve the building and the need to not harm the bats — likely little brown bats — which are protected as their ranks are thinned by white nose syndrome.

Grange members first noticed flaking material from the building’s tin ceiling a couple of years ago and thought it was from mice. Then the occasional bat would swoop through the hall and members realized it wasn’t mice — it was bats.

“We found later it was bat guano on the seats,” she said. “They’ve decided this is a great place to have their young. They do it every year. It’s a comfortable place to come back to.”

Bailey said it’s going to cost as much as $6,000 to remove the guano, and “then after it’s removed we have to plug every hole that they come in from and then we have to do whatever it’s going to take to save the tin ceiling,” Bailey said.

The whole job could take as much as $10,000, she said. With events and fundraising, the Grange only has about $5,000 annually to work with, she said.

The molded tin ceiling, installed when the hall was built in the late 1890s, is stained with rusted, brown spots from the guano.

The Grange’s annual dinner theater is held in the upstairs once a year and is the organization’s biggest fundraiser, she said.

“We’re trying to preserve the building,” Bailey said. “We like the Grange as a meeting place. The bats are going to come back if we let them.”

The bats get one more year in the Grange. They’ll be monitored this year, and once it’s determined how they’re getting into the building, the holes will be plugged and they’ll have to find a new home next year.

Bailey said the Grange is also trying to get area residents to install bat boxes on their property to divert the creatures away from the building.

Meanwhile, the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, which is behind the monitoring effort, is using the issue as a teaching opportunity. Cory Mosby, a biologist with the department, will give a talk on bats at the Grange Monday, May 9

PROTECTED SPECIES

The bats hibernate farther south during the winter and are getting ready to return to the building, possibly by early May, when there are plenty of insects to feed on.

Mosby recently visited the Grange and on Friday sent a technician to install a bat monitoring system to see exactly what species of bat is present in the attic. Mosby determined from the guano that little brown bats have lived at the Grange, though that could be remnants from past colonies, and it may be big brown bats now living there as the smaller bats become more scarce.

Mosby won’t know for sure about this year’s return until he can look at the acoustic data from the monitor and from area volunteers counting bats at dusk.

The monitoring system is a recording box that turns itself on at sunset and off at sunrise. It has a microphone that can record ultra high frequencies, because bats make noises that are above the audible range for humans.

Little brown bats possess a high sense of fidelity to a maternity site — a hollow tree, an attic or a barn eave — and will return year after year to the same place, as will their offspring. Mosby said a bat can live 30 years, so there would be many generations born in the same place.

The bats returned to the hall last season, so it is safe to believe they will return this season, making it still an active site, he said.

The species has suffered “a catastrophic population decline” from the fungus that causes white nose syndrome, making them protected mammals in Maine under the Endangered Species Act.

White nose syndrome is caused by a fungus that invades the bodies of bats while they hibernate. Mosby said the fungus is only found in cold, dark places such as caves and mines where the bats hibernate, not attics and not at the Grange hall.

The fungus will show up around the muzzle or nose area, but the major damage that is done is a skin infection of the flight membranes. With their wings damaged by the fungus, bats are less able to keep warm, meaning they burn through their fat reserves more quickly in the winter while they hibernate. Even more deadly is the impact on their flying ability. Some infected bats can’t fly at all. Others can fly, but not as well, making it much more difficult for them to corner and consume insects.

‘WE DON’T WANT TO KILL THEM’

The benefits of having bats around far outweigh the problems, according to the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries & Wildlife website. As predators of night-flying insects, including mosquitoes, bats play a role in preserving the natural balance of an area.

Although swallows and other bird species consume large numbers of flying insects, they generally feed only in daylight. When night falls, bats take over. A nursing female little brown bat, for example, may consume her body weight in insects each night during the summer.

Bats, the only true flying mammals, are not blind and do not fly into people’s hair.

“If a bat comes close to your head, it’s probably because it is hunting insects that have been attracted by your body heat,” according to the website. “Less than one bat in twenty thousand has rabies, and no bats in Maine feed on blood.”

Bailey said each year the interior of the Grange has a flying visitor or two and, as the bats fly around, she leaves.

“I don’t like bats,” she said. “It’s ironic. I don’t like bats and here I am trying to save them — save the hall and save the bats. We don’t want to kill them.”

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

Twitter:@Doug_Harlow

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.