EAST MACHIAS — Christopher T. Knight, the man known as the North Pond hermit, spent almost three decades carrying items he stole from camps and cottages to his rural Rome campsite.

On Thursday morning, his attorney, Walter McKee, said Knight should not be obliged to pay for the repair of damages Maine State Police caused in the spring of 2013 when they drove on a dirt camp road to disassemble that campsite.

The state, through Kennebec County Deputy District Attorney Paul Cavanaugh, told a panel of six judges of the Maine Supreme Judicial Court that Knight should pay $1,125 for the gravel and regrading police did to restore that road.

“This was not an environmental cleanup,” McKee said, referring to one of the items covered in the state’s restitution statute.

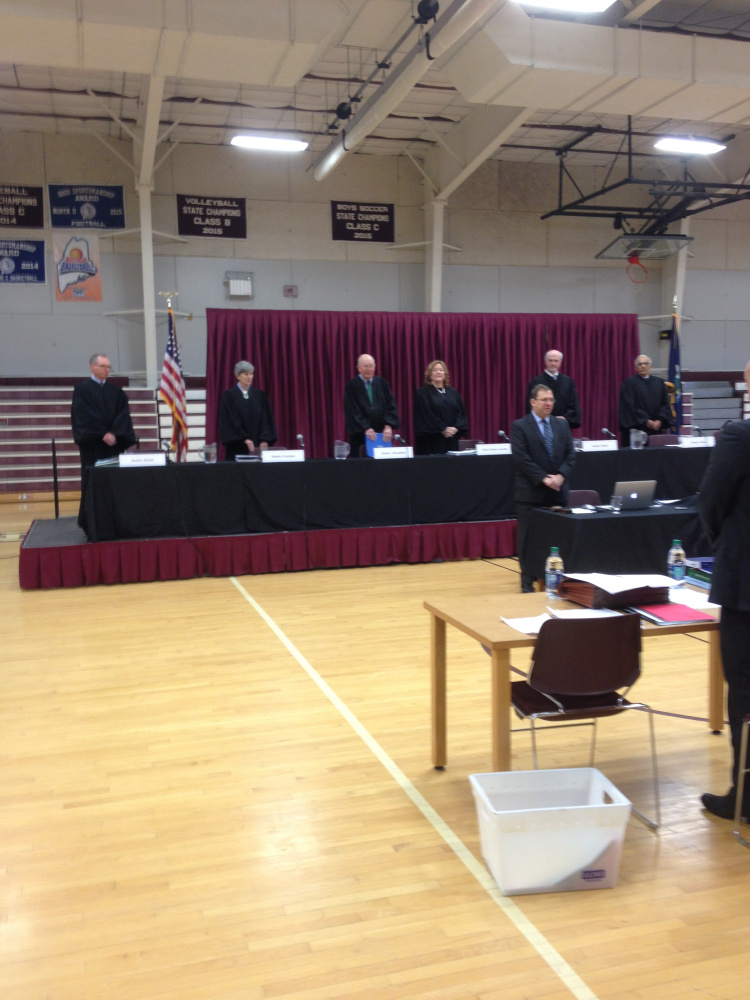

Oral arguments in the appeal were held during a session the court held at Washington Academy, where about 425 students and their teachers sat in bleachers and in chairs on the gymnasium floor to watch the proceedings. The makeshift courtroom was as quiet as the supreme court’s formal courtroom in the Cumberland County Courthouse.

Knight, who remains on probation, did not attend the hearing.

Knight grew up in Albion, then left civilized society after high school, spending some 27 years alone in the woods in campsites he outfitted with items stolen from Rome and Smithfield cottages and camps. The mysterious break-ins spawned the local legend of a “North Pond hermit.” Authorities caught Knight breaking into the Pine Tree Camp three years ago, and the case drew worldwide media attention.

In 2015, after completing a specialty court program for people with mental health and substance abuse problems, Knight was sentenced on burglary and theft charges and ordered to serve seven months in jail — time he had already served — and the remainder of the five-year sentence was suspended. He is now serving the three-year period of probation, which ends March 22, 2018, according to the state Department of Corrections website.

On Thursday, Cavanaugh said Knight was meeting the conditions of that probation, including paying $25 a month toward restitution. In fact, after the hearing, Cavanaugh referred to a note provided by Knight’s probation officer, which said Knight reports to her as required, remains in treatment and most recently sent in $40 toward restitution.

Cavanaugh said there was no indication that Knight was employed.

McKee, too, said he did not know whether Knight had a job.

Knight, 50, has remained almost hermitlike with regard to any publicity and interviews, and McKee said Knight has declined numerous interview requests. During the hearing, McKee also said Knight does not have the money to pay for the road repair, and that he should not have to because the road repair was “so far attenuated or removed from the crime for which he was convicted” and could lead to numerous other costs assessed to people, such as a bridge built to an island so firefighters could fight a fire.

“There are no individual victims here,” McKee said. “The victims are the state police.”

Associate Justice Andrew Mead asked whether the state was trying to make the defendant underwrite the cost of the investigation.

Associate Justice Jeffrey Hjelm asked whether there had been prior attempts to resolve the dispute over the road repair money.

“The amount of money at issue here is a little over $1,000,” he said. “The amount of money expended on this appeal far exceeds that.”

McKee responded that attorneys had attempted a resolution but failed.

“Chris could not agree to this issue,” McKee said. “He is very principled. He said, ‘I am willing to pay for what I took from people; that is perfectly appropriate. I am willing to do my time, so to speak. But I’m not willing to pay for money for what the state police expended for fixing a road as part of their work.'”

Hjelm also noted that the woman who owned the property where Knight had his camp was not named as a victim of any of the crimes.

“For there to be consideration of restitution, the person who is entitled to the money has to be the named victim of the charges,” Hjelm said.

McKee said Knight paid restitution to the state “for the actual victims here.”

McKee said the statute under which the restitution is being sought was aimed at costs of cleaning such items as methamphetamine laboratories.

Associate Justice Ellen Gorman asked, “Why should the restitution statute be read to say in addition to what the public already does to pay for the investigations and to pay for what they do to investigate and prosecute crimes, we should also require other persons to pay for that work?”

Cavanaugh said criminals should bear the financial burden.

“Between the innocent taxpayer supporting the state police or the criminal that caused that, it should be more about a criminal,” Cavanaugh said.

During the hearing, Chief Justice Leigh Saufley asked Cavanaugh whether the court should impose the “rule of lenity” and side with the defendant when the law was not crystal clear.

Cavanaugh said, “Despite Mr. McKee’s arguments, it is crystal clear that it is covered.”

At one point, she also asked how Knight’s plea was constructed “with this, this sort of hanging chad.”

Cavanaugh said the issue about payment for the repair of the road came up at the sentencing hearing once Knight finished the diversionary court program.

The Maine Supreme Judicial Court issues its decisions later in writing.

Betty Adams — 621-5631

Twitter: @betadams

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.