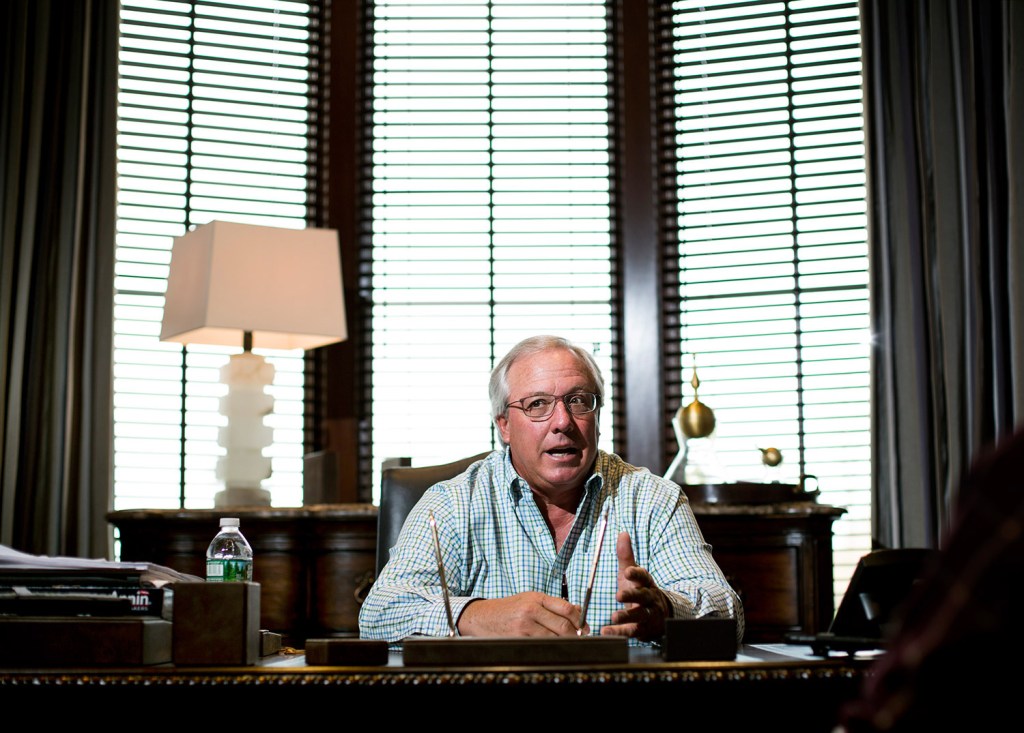

Soon after Paul Coulombe purchased the Boothbay Country Club in early 2013, he quietly began acquiring property adjacent to the neglected golf course. He had grand plans and needed the geographic flexibility to execute them.

Most property owners – more than two dozen in all – were happy to sell to the extraordinarily deep-pocketed Coulombe, but some held out. George Whitten was one of them. It had always been Whitten’s dream to live on a golf course, even if, at age 91, he couldn’t play anymore.

But Coulombe wanted to buy Whitten out, demolish the house and replace it with a new driving range and practice facility. He twice went to Whitten with an offer and was twice rebuffed.

Then Coulombe approached Whitten one last time with a new offer.

“I said, ‘Hey George, I really need your house. I need the range,’ ” Coulombe recalled during an interview last month. “I said, ‘We can do two things: I can offer you enough money to pay whatever you’ve got in it or I can put the range in and put a big black net around your house. So whichever way you want to do it, I’m OK with.'”

The next morning, Whitten called and agreed to sell.

Since then, Coulombe has seen few impediments stand in his way as he seeks to remake the town of Boothbay into a tourist destination to rival other coastal Maine communities. He has used his wealth both to strategically buy property and to secure goodwill through donations to well-loved local institutions like the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens and the Boothbay Opera House.

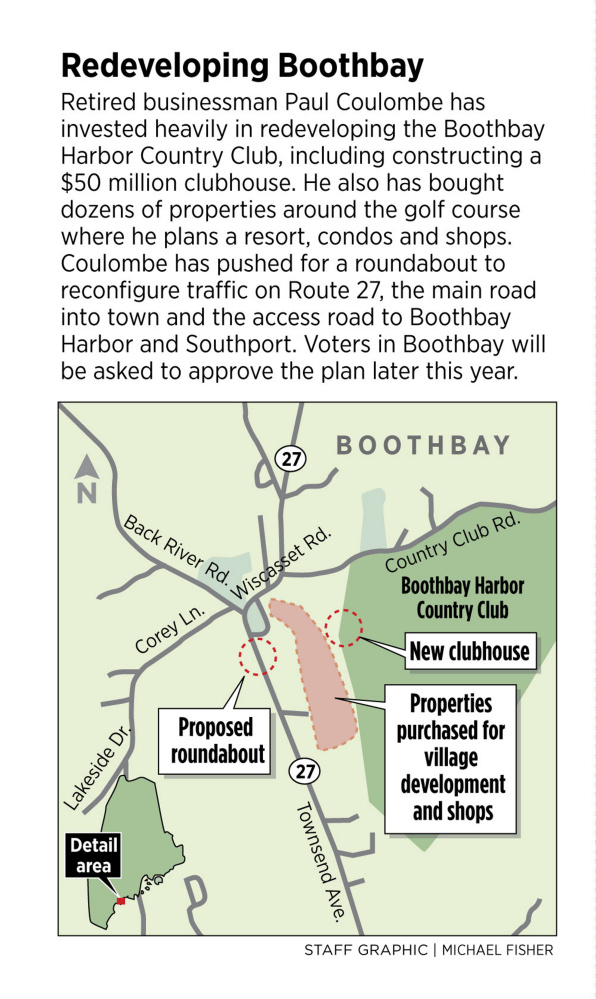

The centerpiece of his development is the revamped golf course, which he renamed Boothbay Harbor Country Club even though it’s entirely in the town of Boothbay, and a brand-new $50 million clubhouse/restaurant that had its grand opening last month.

But Coulombe, who famously sold his former business, White Rock Distilleries of Lewiston, for $600 million to Jim Beam four years ago, is far from done. His vision for Boothbay includes a four-star resort and spa to pair with his high-end golf facility, a suite of condominiums with views of the course and a nearby town village of boutique shops. After that, who knows, although he hinted at a new marina in the harbor as well as more waterfront hotels.

Asked why he’s doing it, Coulombe said he wants Boothbay to surpass Kennebunkport or Camden or even Bar Harbor in drawing tourists with money to spend.

“I’m trying to put the peninsula on the map,” he said. “Someone in 1958 or something put a closed sign out there. No one has invested. And the people who live here don’t understand what it could be.”

Although some residents have objected to Coulombe’s plans for various reasons – it’s too much, it’s too fast, it’s too luxurious – he has mostly been able to do what he wants because everything has been on private property.

His latest effort, though, to establish a roundabout that would reconfigure traffic on Route 27 and greatly benefit his current and future developments, depends on something Coulombe has never needed before: majority support from townspeople. The plan will go to a townwide vote later this year.

And some aren’t sure he has enough support.

Fred Kaplan, a local author, has become Coulombe’s most vocal critic at town meetings and in letters to the editor in the weekly newspaper. Kaplan says Coulombe resurrected the idea for a roundabout – an idea that voters rejected only two years ago – and bankrolled a study that supported changing the traffic pattern. Coulombe even offered to pay for one-third of the $3.5 million cost through a public-private partnership between himself, the state and the town.

“Who benefits?” Kaplan asked. “It’s very clear that Paul Coulombe benefits, but what about the rest of the town? He doesn’t give away anything unless there is something in it for him.”

In concerns expressed by Kaplan and others around town, it’s clear that there is a broader fear over the changes coming to their community, an aging, economically stagnant community. Other than Bigelow Labs in East Boothbay, the job market is thin. That means young people are not being attracted or retained. More than 54 percent of Boothbay residents are over the age of 50, compared to 40.5 percent statewide. The town’s population was 3,120 as of the 2010 Census.

It’s not so much that townspeople mind the investment or the new jobs created; they just aren’t sold on Coulombe’s vision.

“He says he’s doing all this for the community, but no one can afford to pay for that course or eat in his restaurant,” said Sumner Lipman, an Augusta attorney and part-time Boothbay resident who has represented clients in lawsuits opposite Coulombe and who admits he has become an enemy. “He’s turning the town into a rich-person destination and the people left are going to be the servants.”

Coulombe brushes aside any criticism with confidence befitting a successful businessman.

“The community has a choice,” he said. “It’s either bring in more people or roll up the sidewalks and go home.”

• • • • •

Coulombe, who grew up in Lewiston and lived for many years in Cape Elizabeth while heading White Rock Distilleries, visited the Boothbay peninsula with his family as a boy and fell in love with its beauty.

Roughly 15 miles off the main Route 1 artery that carries tourists from Kittery all the way to Calais, the region is sometimes overlooked and has a quiet, rustic feel that many locals hold sacred.

Boothbay’s history is steeped in fishing and there are still vestiges of that in the picturesque harbor, where lobster boats with chipped paint occupy the same space as luxury yachts, including some that belong to Coulombe.

He became a part-time resident in 2008 after he bought property on Pratts Island, a small island connected to Southport, a slightly bigger island, connected by bridge to Boothbay Harbor. But he has been spending significantly more time there since he retired in 2012 with his wife, Giselaine.

“I thought when I retired I’d just move here, build my dream house and go sailing and leave everything behind,” Coulombe said. “But I guess you are what you are. I didn’t realize I wasn’t just content to read a book.”

He did build that dream house – an 18,000-square-foot marble complex overlooking the mouth of the Sheepscot River that took four years to complete and includes an infinity pool on the granite ledge. It’s luxurious and grand without being garish, similar to the new clubhouse at the golf course.

While it was being built, some locals lamented the constant rock blasting that was needed to accommodate some features. The heavy trucks needed for construction also damaged the bridge onto Pratts Island, but when it came time to replace it, Coulombe footed the bill.

His initial foray into business development on the peninsula was not as grand as the house or the golf course, but it was plenty controversial.

There was an old snack shack overlooking the boats moored in Cozy Harbor. For decades it was owned and operated by Earl “Gus” Pratt and his wife, Emolyn.

After Gus Pratt died in 2007, the town of Southport purchased the waterfront property, mainly to preserve access for local fishermen to the water.

It sat empty for four years until Coulombe inquired. He said he’d buy the property and renovate it. Townspeople were skeptical, in part because he was still seen as a rich outsider.

When he first approached the town, Coulombe persuaded head Selectman Gerry Gamage to hold a town meeting. Gamage did, but it didn’t go well. He told Coulombe it wasn’t going to work out.

“I told him, ‘It’s too bad you don’t have any guts,’ ” Coulombe said. “I told him ‘Hold another meeting and let me address the town.’ ”

So Gamage did, and Coulombe did. It didn’t happen overnight, but Coulombe got what he wanted. On the site of the former Gus’s now sits Oliver’s, a restaurant named after Coulombe’s grandson that doesn’t quite match the surrounding aesthetic but has proven successful.

Gamage has had several dealings with Coulombe since and has mixed feelings about what he’s done for the region.

“He’s put a lot of money into this area. He’s put people to work and a lot of this wouldn’t happen without him,” Gamage said. “But I’ve always felt true philanthropy is anonymous. There are a lot of people in this area with money but you’d never know it. Paul wants everyone to know.

“He’s a Maine boy, but sometimes I don’t think he gets it.”

• • • • •

Coulombe, 63, grew up in a working-class French-Canadian family in the heavily French-Canadian city of Lewiston.

When his parents, Ray and Cecile, purchased White Rock Distilleries in 1971, the company had just three employees. They expanded it through acquisition and found a niche selling knockoff versions of popular liquors such as Bailey’s Irish Cream.

After graduating from the University of Maine, Coulombe went to work for his parents in sales, traveling all over the country to peddle White Rock’s brands. He said he developed a keen understanding that house marketing and packaging products was just as important as the products themselves.

Coulombe took over when his parents retired in 1995 and expanded the company further. It really started to take off when one of its brands, Three Olives Vodka, started producing flavored versions. That led to the creation of another vodka brand, Pinnacle, and a new flavor, whipped cream, that Coulombe almost nixed but that became wildly popular.

In 2005, Coulombe bought out his three siblings for full control of the company. Two years after that, he sold the Three Olives brand for an undisclosed sum.

In 2012, at age 58, he sold White Rock Distilleries to the parent company of Jim Beam for $605 million.

Suddenly, he was retired with more money than he knew what to do with. So he began to spend it.

In addition to buying property and planning development, he also made donations to Boothbay’s urgent care center, the YMCA, the library and the local land trust.

But even his donations, while always welcome, have been criticized by some who say he’s buying the town so they’ll support him.

Around this time last year, a writer from Boston Magazine profiled Coulombe and his plans for the region. It was not a flattering piece and some of the more inflammatory things in it came directly from Coulombe’s mouth.

“Well, my initial dream, all my life, since I’ve been a little boy has been to own my own town,” he told the magazine.

Coulombe said he was misquoted. He said he always wanted to “plan and create a small town.”

Perhaps the most damaging line in that magazine story, though, was when Coulombe described the inertia of the community and said this about the locals: “They’re all unemployed in the winter and drinking at McSeagull’s. So I don’t think that’s good. I mean, the men still beat their wives.”

Coulombe said he “never said anything like that.” He said he was trying to make a point about seasonal versus year-round employment and how unemployment can lead to problems like substance abuse and domestic violence.

In any case, people in town still talk about that piece with contempt.

Mark Stover, who grew up in Boothbay Harbor and now lives in Boothbay, is one of them. He knows Coulombe a little – they park their boats at the same marina.

“He’s actually been nice to me,” said Stover, who sits on the board of the Opera House, which received a recent donation from Coulombe. “But I think the concern that he’s dividing the town between the haves and the have-nots is real. He’ll create some jobs, and that’s great, but people aren’t going to be able to afford the things he’s building.”

Another example of that, Stover said, is the former Cuckolds Lighthouse off the island of Southport. Like other landmarks in the area, it had been neglected, so Coulombe stepped in to save it. Except now, it’s an exclusive bed-and-breakfast whose rooms go for $500 a night.

• • • • •

To remake the golf course, Coulombe hired Bruce Hepner, a longtime associate of Tom Doak, one of the premier golf course architects in the world.

He then hired as his golf pro Chad Penman, who previously was director of instruction at Calusa Pines Golf Club in Naples, Florida – ranked by Golf Digest as one of the top three courses in all of Florida and one of the top 100 courses in the country.

Membership in the country club is $5,000 for the initiation fee, and $2,900 annually, for Maine residents. Nonresidents pay more: a $10,000 initiation fee and $4,500 annually.

At the grand opening of the clubhouse in May, members marveled at the new facility and said they couldn’t wait to play. Gov. Paul LePage, who is friends with Coulombe and participated in the ribbon-cutting, called it a “world-class facility” that will spur economic development.

Others in town agree that the golf course is vastly improved, but they also point out that the $150 cost to play is roughly triple what it was only a few years ago.

LePage and first lady Ann LePage bought a house in East Boothbay and plan to spend much of their time there after the governor’s second term is over. The region may look even more different by then if Coulombe has his way, although the roundabout plan has proven to be a thorn in his side.

In two public meetings held this spring, dozens of townspeople came armed with questions and skepticism.

Boothbay Town Manager Dan Bryer has been in his position only a year but said he’s heard from many other town managers in Maine who would like to have his problem: a wealthy investor who wants to build the tax base. But Bryer said he also understands that the community’s history is important to people and that change is hard.

“Folks are having a say, which is great,” he said. “These meetings are well-attended. And then they get to vote. That’s democracy at its best.”

Coulombe said he doesn’t understand the controversy. The roundabout will improve the road for everyone, tourists and locals alike, and will have zero taxpayer impact.

“We’ve made it a no-brainer. There is no reason to be against it,” he said. “The only reasons people have is that they don’t want change or they fear it. Those are not good reasons.”

To make room for the roundabout, Coulombe purchased the property that houses the town’s ambulance service. The building will be demolished but Coulombe has pledged to fully fund a new ambulance headquarters just south of the existing location.

But critics like Fred Kaplan wonder if Coulombe’s political influence has helped him secure support from the Department of Transportation. He is friendly to the governor, but also is the single biggest donor to the Maine Republican Party and has hosted fundraisers for U.S. Sen. Susan Collins at his Southport home. Since 2010, he’s given nearly $300,000 to the state party.

DOT officials, though, said private-public partnerships for road improvements are becoming more and more common and they welcome investors like Coulombe.

Jane LaFleur is director of the Friends of Midcoast Maine, a nonprofit group that works with coastal communities from Brunswick to Bucksport to implement Smart Growth principles, which means environmentally conscious, anti-sprawl development. She said communities like Boothbay always face competing interests when it comes to new development.

“Change is hard,” she said. “The more we grow and change outside of historic patterns, we’re less compatible with the lifestyle people appreciate.”

Coulombe thinks people will come around once they see he’s serious, that he’s not just trying to take over the town. He says he has been and will continue to be mindful of development that matches the area’s New England charm.

“I’m trying to attract other money, too,” he said. “I’ve talked with other investors and businesspeople but lot of people have turned me down because I can’t convince them yet that there is a good return on investment.”

• • • • •

Even if the roundabout goes through, it probably won’t always be smooth sailing for Coulombe.

He has his sights on other properties whose owners may never sell. Among them are Jim and Ginny Farrin, who own the Howard House, a bed-and-breakfast just south of the proposed roundabout, and another 6 acres behind it that abut the golf course parcel.

The Farrins declined to comment but Coulombe acknowledged his interest in their land. He joked that he may need to “outlive them.”

Then there are Derek and Rebecca Abbott, who own a horse stable that borders the back edge of the golf course. Lipman, the attorney who has represented others in lawsuits against Coulombe, has taken the Abbotts’ case, too.

Coulombe sued the couple over a right of way between their property and the course. He doesn’t want the Abbotts to use it and he really doesn’t want the horses using it. Lipman has counter-sued Coulombe and is girding for a fight.

“If you don’t sell, he makes life miserable. He’s vindictive,” Lipman said. “He basically told my clients, as a way of trying to get them to give up, ‘I’ve got a lot more money than you.’ He’s a bully. The bully of Boothbay.”

Kaplan had a similar experience at a public meeting in April to discuss the roundabout, where Coulombe fielded questions. Kaplan wanted to know if Coulombe was prepared to put in writing a guarantee that the town wouldn’t be on the hook if something were to happen to Coulombe.

“He was offended,” Kaplan said. “He said to me, ‘What have you done for this town?’ Of course, what he really meant was, ‘How much money have you put into this town?’ But everyone gives in different ways.”

Coulombe has gotten most of what he wants, but he has lost, too. In 2013, he sought permission from the town to dredge the harbor near his home on Southport so it could accommodate his boat. After pushback from townspeople and conservationists, that plan was scrapped.

Coulombe said he doesn’t worry about convincing everyone. He said he’s fine with 90 or 95 percent support.

And, he said, people are coming around all the time.

Bet Finocchiaro, proprietor of the popular Bet’s Fish Fry that is situated near the winding new entrance to Coulombe’s golf club, once had concerns about the man. Now, she’s willing to give him a chance.

And George Whitten, the now-93-year-old who reluctantly sold his house after Coulombe threatened to put a giant net around it, has become a fan, too.

At the ribbon cutting for the clubhouse last month, Coulombe asked Whitten, a veteran of World War II, to do the honor of raising the American flag.

This story was corrected at 10:47 a.m. on Sunday, June 5. Because of a reporter’s error, the original published version was incorrect about the background of one of his critics. Fred Kaplan did not serve in Vietnam; he was an anti-war protestor. The story was also unclear about Coulombe’s donation to the local hospital. He gave $1.1 million to the urgent care center in Boothbay after the hospital closed.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.