When Hunter Praul walked onto the stage at China Middle School’s Eighth Grade Recognition Ceremony on June 9, his mother was so overcome by emotion she felt sick. Erika Praul hadn’t known her son was going to speak.

After Hunter made a short speech to the more than 500 people packed into the gym, they erupted into applause and cheers.

His parents, Darryl and Erika Praul, were in tears.

The moment was a culmination of years of work by Hunter and his parents.

On a recent afternoon at his house in South China, Hunter worked at his woodworking bench, chipping away at a piece of wood with a small metal tool called a gouge. After a few minutes of striking down on the wood and carving off layers, a pile of thin wood chips lay at his feet.

“I think it helps relieve tension,” said Erika, 47, as she sat nearby.

As Hunter worked, his mother reflected on what brought them to that moment in the auditorium.

Hunter, 13, has selective mutism, a childhood disorder rooted in anxiety that makes it difficult or impossible to talk in certain social situations. The intense anxiety is caused by hormones activating the adrenal system, the one that signals a person’s fight, flight or freeze instincts.

Hunter’s parents first mentioned to a pediatrician that he wasn’t speaking in school when he was in first grade. The pediatrician diagnosed Hunter with selective mutism, Darryl said.

She said he’s a good pediatrician, “but I wish he hadn’t been so casual” about the diagnosis.

Erika also had selective mutism, she believes, although she was never diagnosed. She started to talk in school in second grade, so the Prauls, along with some of their doctors, thought Hunter might grow out of it to an extent, although Erika knew the anxiety would never completely go away. Their two other children, Jacob, who’s older than Hunter, and Sarah, who is younger, don’t have the disorder.

Annie DiVello, a speech-language pathologist at New England Pediatric Services, of Bedford, New Hampshire, said the anxiety “derails the entire language process.”

The fight, flight or freeze response, she said, is what we used to have when a saber-toothed tiger attacked us in prehistoric times, for example. This is how people feel when they’re alarmed, and it can lead to a slower heart rate, slower respiration and a drop in blood pressure, which causes the blood to coagulate to prepare for an attack.

“These children are feeling this over and over again all day,” she said.

MISTREATED, MISUNDERSTOOD

Hunter’s parents had seen several local doctors and psychologists, but none had enough expertise in the disorder to help the Prauls.

The closest experts for those who live in Maine are in New Hampshire, a few hours away, and make up a team of therapists and psychologists with whom DiVello works.

The Prauls eventually took Hunter to New Hampshire to get more in-depth help with his diagnosis.

The disorder “remains one of the most mistreated and misunderstood” even now, DiVello said during a phone conference Wednesday. If caught early enough, a child can learn compensatory strategies to deal with the anxiety and prevent going mute when nervous, she said.

Selective mutism is explained by a diathesis-stress model, which is a psychological theory that the behavior stems from both a predisposed vulnerability and life stresses.

“There’s a real physiological component to the anxiety,” said Beth Doppler-Bourassa, a clinical psychologist at The Village Counsel PLLC, in Dover, New Hampshire, who works with DiVello’s team to help children with the disorder.

Parents often have an “ah-ha moment” when learning about a child’s diagnosis, she said, because they realize they were affected with the same disorder but never diagnosed. While it’s not characterized as a genetic disorder, it can be inherited.

Children with the disorder are very layered, DiVello said, which is why she pairs families with a team of two speech-language pathologists, an occupational therapist and a clinical psychologist. More than 80 percent of children with selective mutism have a co-existing condition.

In 1980, the disorder was called elective mutism in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, but its name was changed in 1994 to reflect the fact that the affected children can’t speak, rather than won’t. Studies have shown that those affected experience a significant tightening in their larynx when their anxiety response begins, DiVello said. On average, affected children miss 100 or more social opportunities each day.

“To put it simply, imagine being locked in a world of social invisibility,” Doppler-Bourassa said.

Some experts say that selective mutism is likely more prevalent than autism, but it’s often not diagnosed, or misdiagnosed as autism or developmental delay, she said.

While up to date numbers are not completely clear because of a lack of awareness and research, 1 in 143 children are diagnosed with selective mutism, according to research from 2002, DiVello said. Today 1 in 83 children are diagnosed with autism.

A WORLD OF SILENCE

Most people realize their children have selective mutism when they enter school or daycare, DiVello said. Before then, the children can talk to their family and people they see often because they feel comfortable, but once they transition into a new social setting, the anxiety will start to appear.

The New England Pediatric Services, where DiVello works, sees 4- to 6-year-olds for selective mutism most often.

While early intervention is better, it is never too late to put supports in place and help a child cope with the disorder, DiVello said. Once children reach high school age, though, she recommends medication in addition to therapy. Without intervention, the disorder remains the same or grows stronger.

After an initial phone call and meeting, a number of surveys and tests for children, parents and teachers are completed to give the team at New England Pediatric Services an idea of the child’s ability. The occupational therapist, Erica Brown, will look at sensory integration in the child. First, she’ll get the child moving — in a ball pit, for example — to help ease the child out of fight, flight or freeze mode to a more regulated state. Without movement, DiVello said, children can get stuck in a “frozen” state where they can’t access the cerebellum.

Once the child gains more access to communication, Brown will progress the child up a “verbal ladder” from a thumbs up to one word or some variation. This lets her know how far along the child is in coping with the anxiety.

Brown sends therapy instructions home for children to do with parents, which can be especially helpful for “transitions” — before a big trip, after the school day or when arriving at a restaurant.

This physical component is what separates NEPS from other centers in the country that focus on selective mutism.

“We’re really treating the whole child,” she said.

The children DiVello and her team see are typically on the high end of the intelligence scale. They test children with the fourth edition of the Pearson Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, where the average score is between 85 and 115. Most of their children score in the higher end of this range or above it, she said.

Research shows that people who tend to be anxious also tend to have a higher verbal IQ, according to Doppler-Bourassa, so children with selective mutism might have a lot to say, but are just unable to say any of it.

“These children suffer,” DiVello said. “They truly suffer in a world of silence.”

‘COMMUNICATION WAS THERE’

While Hunter chipped away at the wood on his porch, the wind carried a smell around to the porch from the yard.

It’s roadkill that he’s breaking down to get the bones to look at with his teacher, his mother said.

His science teacher, Ron Maxwell, started working at China Middle School in 1998 and said he’d never taught a student with selective mutism before. He conceded in an interview he was anxious about how he would communicate with Hunter when he found out the student had trouble speaking with some people.

But while Hunter never verbally communicated with him during class time, Maxwell said he didn’t feel like they lacked communication at all.

“I never once thought I didn’t know him like the other (students),” he said. “The communication link was there.”

Whether it was through a thumbs up or down, a written answer or a “fist to five” rating how well he understood material, Hunter got his point across.

“I never really wanted for any other communication,” Maxwell said. “He’s got a full range of direct answers to direct questions.”

Hunter has expression-filled eyes and Maxwell can read him “just like any other kid,” Maxwell said.

One day, Hunter brought in a dead squirrel his father had helped him put in a bag — both of Hunter’s parents are veterinarians at Windsor Veterinary Clinic.

Over the past six months or so, Maxwell and Hunter have gone through the process of reclaiming bones from dead animals using different treatments, like bleach or Listerine. A porcupine was in the bucket in the yard.

Maxwell’s favorite part of teaching Hunter is that they get to “play with dead things” together, which he hasn’t gotten to do since college.

“There are students who do exactly what you tell them to, those you have to move to do something … and then there are students who learn in spite of me,” Maxwell said. “Hunter will learn in spite of me.”

POKING TIN FOIL

Erika and Darryl Praul wish they’d gotten Hunter more help when he was younger.

They felt his pediatrician, while liked by both parents, was too casual about the issue.

“Since kindergarten, I thought, ‘He’s just so close,'” Erika said.

Darryl encouraged Hunter to try to be more social and confident. He always felt Hunter could do it.

Both parents were concerned, as Hunter got older, about his progress. It’s rare for selective mutism to continue into middle school and high school, Erika said, so they decided to get more proactive.

Hunter started medication about 10 months ago, during the summer, so it could be a transition time before school started, Darryl, 47, said.

While the first medication didn’t seem to work, fluoxetine, an antidepressant, did. Hunter still takes it and has made great progress over the past school year, according to Darryl. Hunter has also been working with an occupational therapist to learn relaxation techniques and coping mechanisms.

This year Hunter met his goal of talking to a teacher for a couple minutes in between classes or during lunch. Last year, he would communicate with his teachers solely through writing.

He’s also been talking to his Boy Scout leaders one-on-one for the past few months, which he didn’t do before. At a meeting to move up in the rankings, Hunter also answered questions from multiple leaders at once, which was a big step, Darryl said.

In December, he talked over the public announcements system at school before the morning announcements were made.

“He screws up his courage and boom — does something,” Darryl said.

There can also be setbacks, like a recent trip to a restaurant with one of Hunter’s friends, where he wasn’t able to order for himself in front of the table.

To help Hunter deal with transitions, like moving from China Middle School to Erskine Academy in South China, the parents prepare ahead. Darryl said he introduced Hunter to all of his teachers at Erskine and met his school adviser.

China Middle School was a good place for Hunter too, his parents said. He was never ostracized, and most of the other children and all of the staff were supportive.

Outside of school, Hunter said he likes to go fishing with his friends at the China boat landing. He said he’d like to be a biologist when he grows up. He also catches frogs, which are his favorite animals. The next woodcarving piece he plans to make will be of a frog, he said.

“(The wall) will always be there,” Erika said.

“It’s like poking a tin foil wall with a toothpick,” Darryl said.

CENTER STAGE

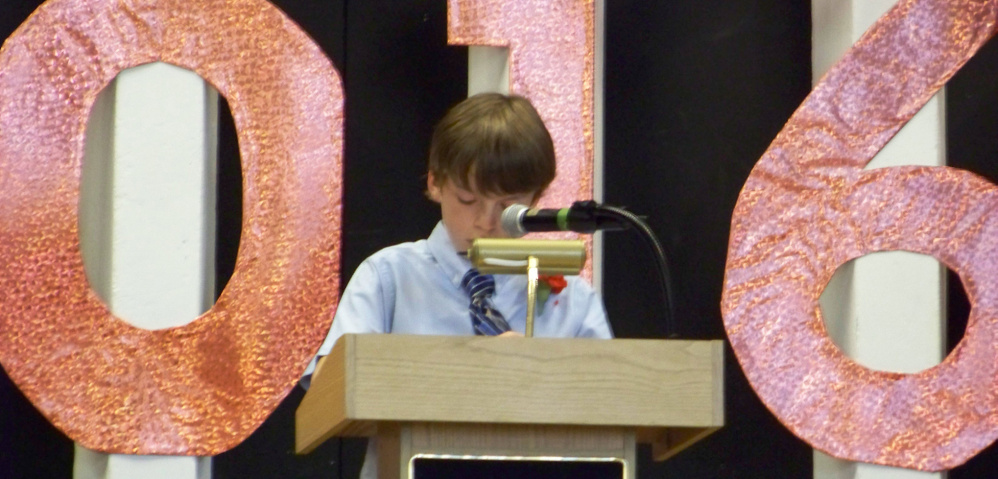

The biggest accomplishment came when Hunter took center stage at last month’s school recognition ceremony.

“That was so insanely out of the blue that he did that,” Darryl said. No one in their family was expecting him to speak.

But Hunter’s older brother, Jacob, was getting a pet parakeet that weekend, and Hunter wanted one, too. When he asked his father what he could do to get a parakeet, Darryl joked that he’d have to give a speech at graduation.

Before the ceremony began, Hunter showed his father that he’d written a short speech and asked if he could talk. His father asked Meg Childs, a teacher at the school, who said they’d let him speak before the slideshow.

When the ceremony started, the teachers and the student speaker — and Hunter — walked onto the stage in front of the gym filled with eighth graders and their families.

Erika didn’t know that Hunter was planning on speaking, and she felt emotional and nauseated when he went to the microphone. Most people in the audience were emotional, too, and some were crying, she said.

Hunter walked up to the podium with his speech in hand.

He said hello to the crowd of more than 500, thanked the teachers for a great year and introduced the slideshow.

When he finished and walked back to his seat, the gym erupted in applause and cheers.

Hunter said last week he felt proud when he finished his speech.

And while he didn’t get a parakeet, he did get the new computer he’d been working toward the whole year.

Darryl, who worried about what Hunter’s adult life might look like if he didn’t keep progressing, felt relief.

“Him doing this — now I know he’s gonna be OK,” he said.

Madeline St. Amour – 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.