EAST MADISON — When Aren LeBrun left rural East Madison after high school in 2012 for college in Boston, it didn’t take him long to notice the disparity between college privilege and life in sections of the city that bordered his school, Northeastern University.

Mattapan, Roxbury and Dorchester are mostly black and Latino neighborhoods and some of the city’s poorest, most crime-ridden areas.

LeBrun, a journalism and media studies major, was introduced during his course work to news stories about Boston families and groups fighting for justice and open records in the city’s 900-plus unsolved homicides in those three neighborhoods. He was drawn in, he said, to the reality of life and death in a world he’d never seen before, and he wanted to tell their stories.

“Being from Maine, a state that is both ultra-white and thankfully low-crime, it was a disappointing reality check that there are men, women and children in our country who are forced to live with this level of poverty and violence every single day, with little to no chance of escaping it,” LeBrun, 22, said this week. “Basically it felt so un-American to me that in a major city like Boston, your chances of survival depend on something as choiceless as the neighborhood where you are born.”

LeBrun, a graduate of Skowhegan Area High School, produced two short videos telling the stories of families of color who’d lost a member to a murder that had yet to be solved. Both films won first place in the New England National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Award College/University category — the Boston/New England Emmy Awards ceremony.

The awards for “Legacy Lives On” in 2015 and “The Outspoken Survivors” this year were in the Short Form — Non-Fiction category for college and university students under Northeastern professor Mike Beaudet, an award-winning journalist who has worked in television news for more than 20 years.

Lebrun, who worked with two other students on the first film and went solo on the second, accepted the award in June at the 38th annual Boston/New England Emmy Awards.

The Northeastern University campus is near the three neighborhoods LeBrun features in his videos.

“Being from Maine, everything is so spread out,” LeBrun said. “You’d have to go a long way to get to a place that was as impoverished as Roxbury is. Here, you’d only have to go several hundred yards in one direction and, if you’re born there, your chances at success or survival are a lot lower — literally a couple of football fields away from Northeastern.”

‘MY FAMILY’S NOT THE SAME’

“I feel that with media coverage comes empathy,” LeBrun said. “You don’t get empathy when you’re just a number on a page or a statistic on a spreadsheet in some police department.”

In the fall of 2014, LeBrun learned of a support group made up mostly of mothers and sisters of men and boys who were killed in those three neighborhoods. The group is called Legacy Lives On. The president of the group is Clarissa Turner, whose son Willy Marquis Turner was killed in November 2011 in a gang-related case of mistaken identity. He was shot in the back of the head, assassination style. He was 25.

“I called her first and asked her if I could come to a meeting,” he said. “I said I wanted to cover (her) group and maybe do a profile on (her) son, and she was pretty excited. I pitched it — because it was true — that I don’t think these stories get told enough. They were just numbers on a page.”

LeBrun met with Turner and her son Rakim in Roxbury for about two hours on camera. The result was the first video, “Legacy Lives On.”

The video is only a little more than four minutes long, but Turner’s words were powerful.

“My family’s not the same. We try hard every day to just keep pushing and pushing because we have to,” she says into the camera. “It is a journey and my journey continues every day of my life.”

The video also features family members of two other young black men killed in their community.

LeBrun said that while people in black communities are sometimes the victims of police misconduct and black-on-black crime, the Boston stories he tells are about poor-on-poor crime in minority communities.

He said that as a white guy from Maine, he was nervous at first about meeting with the families of murder victims in communities that are exclusively nonwhite.

“I did my best to approach the situations with as much seriousness and respect as possible and to let everyone know that our goals were the same — to teach the public about your loved one in a way that’s bigger and more human than some random statistic on a page,” he said. “It’s very easy for people — especially people from safe, white, middle-class communities like ours — not to empathize with some poor inner-city black families whom they don’t know and rather to blame those families for their situation.”

LeBrun said some of the people at the Legacy meeting he attended were wary of him at first, “not expecting some kid to show up to their session with a bulky camera and sound gear.”

At one point Turner gave him the floor of the meeting and he explained his motives in producing the video.

“I just went on instinct and explained the nature of my project,” he said. “I was very aware of the natural tension in the room. I was an outsider and I really was afraid that I might come off as infiltrating these grieving people’s safe space.”

By the end of the session, all 15 people in attendance agreed to be interviewed, seeing LeBrun not as an infiltrator, but someone whom they trusted to tell their stories.

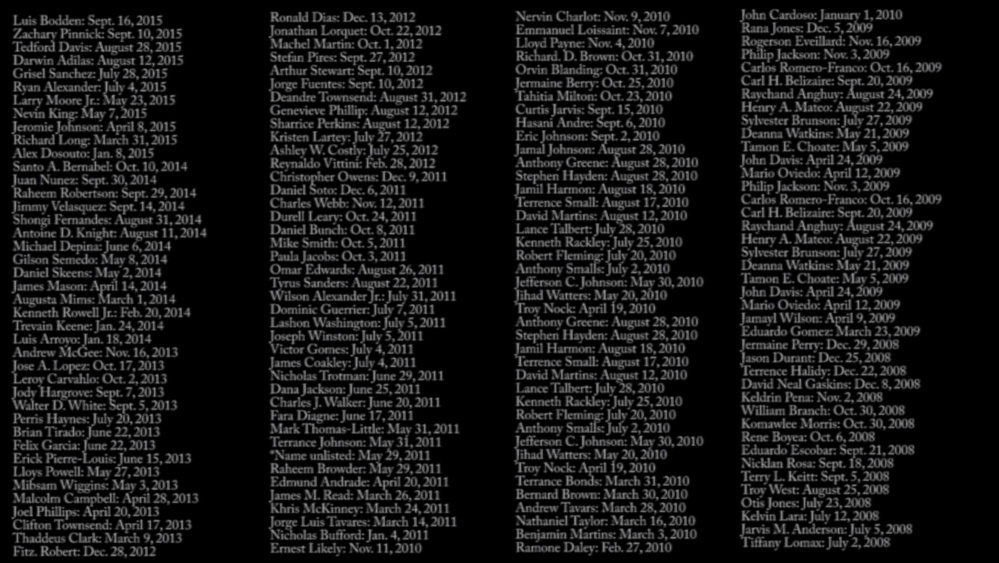

A year after his first video award, LeBrun read a news story about Mary Franklin, the president and founder of the Women Survivors of Homicide Movement. In the Boston Herald story, Boston City Councilor Tito Jackson called on police to create a cold case squad to clear “the grim backlog” of 925 unsolved murders in Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury between 1970 and fall of 2015.

Another black leader said police needed to answer for incomplete information it handed over in response to a public records request on the killings.

Franklin’s husband, Melvin Franklin, was shot to death in 1996 as he stood on his Dorchester front porch. His murder is still unsolved.

When Franklin requested information, she got the report as a page in a stack of spread sheets.

“The data filing was really shoddy,” LeBrun said of the reports. “There were entire years where there was not even a crime scene address; examples of the gender were wrong.”

Franklin has been pressuring the Boston Police Department and the mayor’s office for better record keeping and for the formation of a cold case squad.

LeBrun said the victims’ families had little power. “Inner city violence, whatever the racial disparity happens to be, in my opinion, it’s poor-on-poor crime, because it has much more to do with your economic reality than your skin color,” he said.

LeBrun interviewed Boston Police Commissioner William Evans for “The Outspoken Survivors.”

“Evans said there is no merit to the claim that police don’t care as much about black crime as white crime,” LeBrun said.

Evans, in the video, says “we never forget a victim” in his appeal to the public to come forward with information. “We work hard with all the survivors to make sure we never forget their loved ones.”

Yet Turner says in the video that “the elephant in the room” is race.

“Race. It does play a part. It will always play a part,” she says. “If the community has a respectful, trusting relationship with the Police Department, I believe that people would come forward more often and give more information.”

‘COMPASSIONATE STORYTELLER’

Beaudet, LeBrun’s professor, said LeBrun excels inside and outside the classroom as a journalism student.

“Aren is one of my top students at Northeastern,” Beaudet said in an email to the Morning Sentinel. “His video work is beyond his years of experience. He’s already producing professional quality stories, as can be seen in his award-winning stories.

“Aren has an incredible eye, a sincere reporting style, and he’s a compassionate storyteller.”

LeBrun said he is relying on social media and Internet sites to show his work. If it’s interesting, poignant and truthful, there will be audiences to look at them, he said.

“I have faith in the way that the internet works, that people will watch it,” he said.

LeBrun said once the videos were featured on the Homicide Watch website, the number of views spiked from 500 or 600 to more than 1,000 hits.

After graduation in December, LeBrun said, he wants to produce a feature-length documentary on violence in major American cities and the national media’s “numbing response” to it. He said when a black man is killed anywhere in the United States, the quick reaction is to pin blame on someone — the police, the community, the economy.

Tell the story about the person, LeBrun said. It’s all about empathy.

“I don’t see enough stories that are profiling that victim as a human being, not as a black man or a cop. This is a person,” he said. “I feel we do ourselves a disservice seeing these victims as sterile numbers on a piece of paper instead of people like you and me. It’s your son, your dad or my brother.”

Doug Harlow — 612-2367

Twitter:@Doug_Harlow

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story