Thomas Moore: one of Maine’s best poets

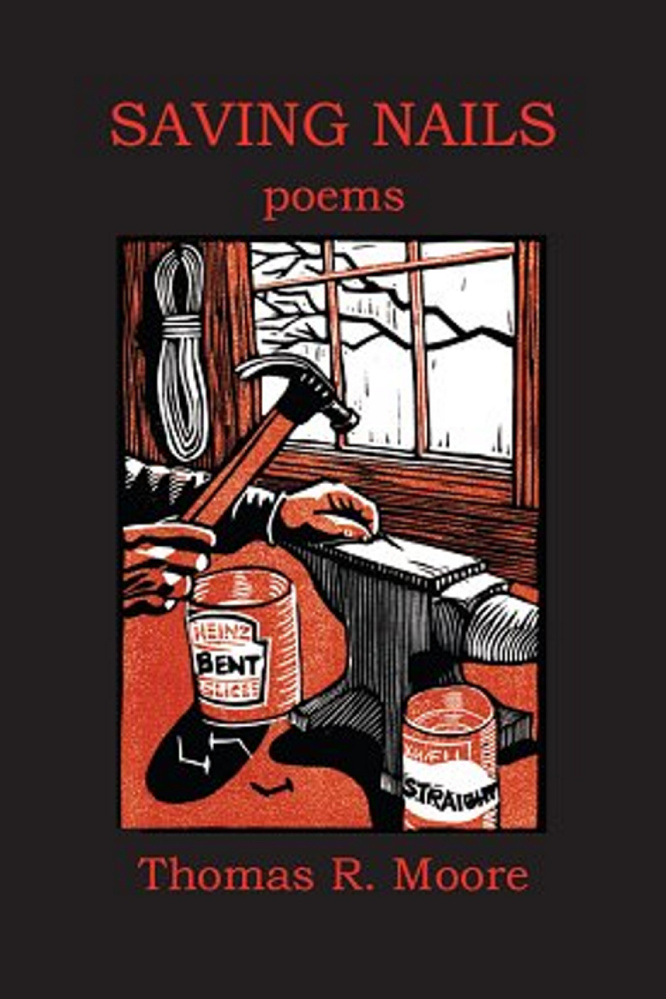

“Saving Nails: poems”

By Thomas R. Moore

Moon Pie Press, Westbrook, Maine, 2016

70 pages, paperback, $14

Tom Moore, who now lives in Belfast after many years in Hancock County where he taught at Maine Maritime Academy, is quietly one of Maine’s best practicing poets.

Or maybe, not so quietly. He’s received a Maine Arts Commission grant. His poems have been featured on Garrison Keillor’s “Writers Almanac” and Ted Kooser’s “American Life in Poetry” and have appeared in long-respected Maine-based literary publications like The Cafe Review as well as in the “Take Heart” and Bangor Daily News “Uni-Verse” columns (both retired). He appears in the online video series “20 Maine Poets Read and Discuss Their Work.” He’s been writer-in-residence at the Elizabeth Bishop House in Nova Scotia. One of his poems was nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and his first two collections of poems, “The Bolt-Cutters” and “Chet Sawing,” were finalists in Maine Literary Awards competitions. “Chet Sawing” won first prize in the Belfast Poetry Festival’s Maine Postmark Poetry Contest.

Accolades in the po-biz world are not particularly hard to come by, to tell you the truth. You could justifiably take a list of accomplishments like this with a grain of salt. So what’s really of interest, on the occasion this fall of the publication of Moore’s third collection, “Saving Nails,” is the word “best.”

What makes poetry “good”? Interesting, unresolvable, much-evaded topic.

When I used to teach literature classes, many students were suspicious of poetry. They said they could not understand it. As far as they knew, poems were puzzles to be solved by brute brain force. This rational detective work seemed to them arcane, or arbitrary. Sometimes it contradicted their own experiences even when they’d stumbled over a poem they thought they understood. They concluded poetry was merely confusing and ultimately meaningless to everyday people.

They had been misled.

Wallace Stevens, an eminent 20th century American poet, wrote: “One reads poetry with one’s nerves.” By this he meant the meaning of poetry is not solved rationally; it is felt. Words do trigger thoughts, which is why the professors get away with forcing you to read a poem as if it is a rebus. But a poem’s thought is usually the least of its meanings.

A poem speaks to the parts of you that get meaning from music and beautiful scenery. It speaks to your emotions, which are often hard to get into rational focus. It speaks to parts of yourself you don’t even know exist until they’re stirred up by the sounds, rhythms, images in words. Stevens also wrote: “Poetry must resist the intelligence almost successfully.” In poetry, it’s not the thought that counts. “To read a poem should be an experience, like experiencing an act,” he said.

So Tom Moore’s poems call up penetrating experiences that are part thoughts, part emotional force, and part strikes on your nerves. He handles the language so deftly that his little narratives from deep in his memory – about his childhood (in the section “Plumb”), or his heart-rending family losses (in “The Voyage of the Red Canoe” section), or the domestic details of his new retirement digs (“How We Built Our House”) – are disarmingly easy to follow but extraordinarily vivid on parts of your consciousness that are usually unconscious. For example, “Gas Man,” in its entirety because the best poems cannot be successfully split into excerpts:

I wept like a little kid, says the gas man

on his hands and knees, his saber saw

rasping through plaster, fiberglass, pine

siding, cedar shingles. Putting your dog

down, holding her when they put in the needle

and feeling her heart slow, then stop, that’ll

do it. Kenny Rogers blasts from the Dead

River truck, door open, in the driveway.

He cannot stand upright. His fingers are bent,

knobby. He moves in smiling pain, lugs

in the new unit, carries out the old, each

a hundred pounds of dead weight. I’ll do

a pressure check, he says, test the system.

He kneels, turns a valve, sees the dog

drawings on the studio wall. The needle spins,

quivers, halts. Eight below is forecast. Our

dog is dead, buried near the window. My wife

can see the stone from her drawing board.

As in his other collections, the world of “Saving Nails” is a place you want your nerves to live in. It’s an assortment of comforting, honest, lucid, heart-piercing, warm, funny, bitter experiences right in the deep heart’s core. When poetry, in language so concisely handled, strikes my nerves like this I call it: very good poetry. Among the best I have read by practicing Maine poets within my reading reach.

“Saving Nails” is available from local book shops, Moon Pie Press (www.moonpiepress.com/catalog.php?BookID=95#details) and online vendors.

Off Radar takes note of books with Maine connections every other week. His book “Summer to Fall” is available from North Country Press (www.northcountrypress.com/summer-to-fall). Contact Dana Wilde at universe@dwildepress.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story