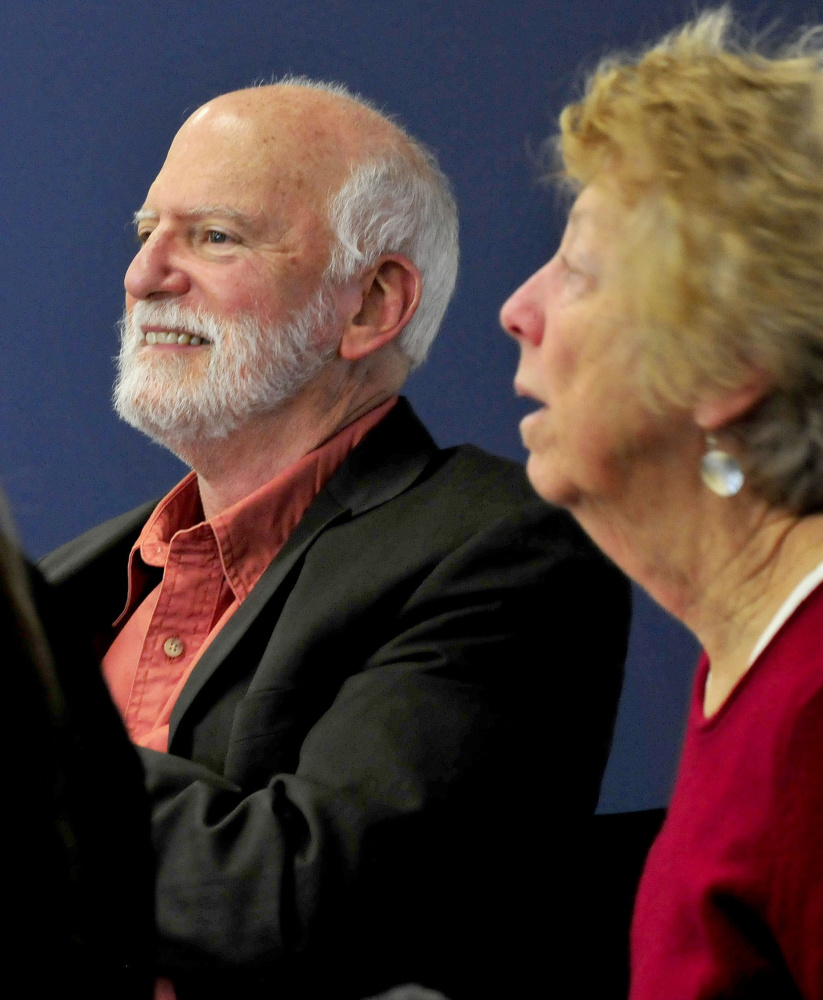

WATERVILLE — Robert Shetterly originally was not interested in painting portraits. The Maine artist made surrealist paintings, but during a discussion at Thomas College, he explained how and why his art transformed.

Speaking to a group of students and faculty members Thursday in the college’s Center for Innovation in Education, Shetterly said he was moved to make a series of portraits in response to how the U.S. government and the administration under President George W. Bush reacted to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, specifically the invasion of Iraq, a military action he said “never needed to happen.” At the time, he said, honest information was not being given to the population, and the press had “rolled over.”

He said he felt as though he was losing his identity and wanted a way to reconnect.

“Fifteen years ago I was in a rage,” he said, because “when you start making a war, there are lots of victims.”

He said that made him think about history and accountability. If people never are held accountable for their actions, he said, how can teachers possibly teach history accurately?

“It was a desperate attempt on my part to reconnect with this country to make me feel good,” he said.

So Shetterly turned his attention to truth-tellers. Rather than look at those abusing power, he decided to focus his efforts on those with the courage to stand up against that abuse. He created a series of portraits titled “Americans Who Tell the Truth” as a way to deal with his grief. He explained to the audience of roughly 50 people that he had intended to do only 50 portraits, and he wasn’t even sure he’d hit that mark.

Today, that collection stands at over 200. The paintings have been to 30 U.S. states, and Shetterly travels the country giving speeches like the one he delivered to Thomas College.

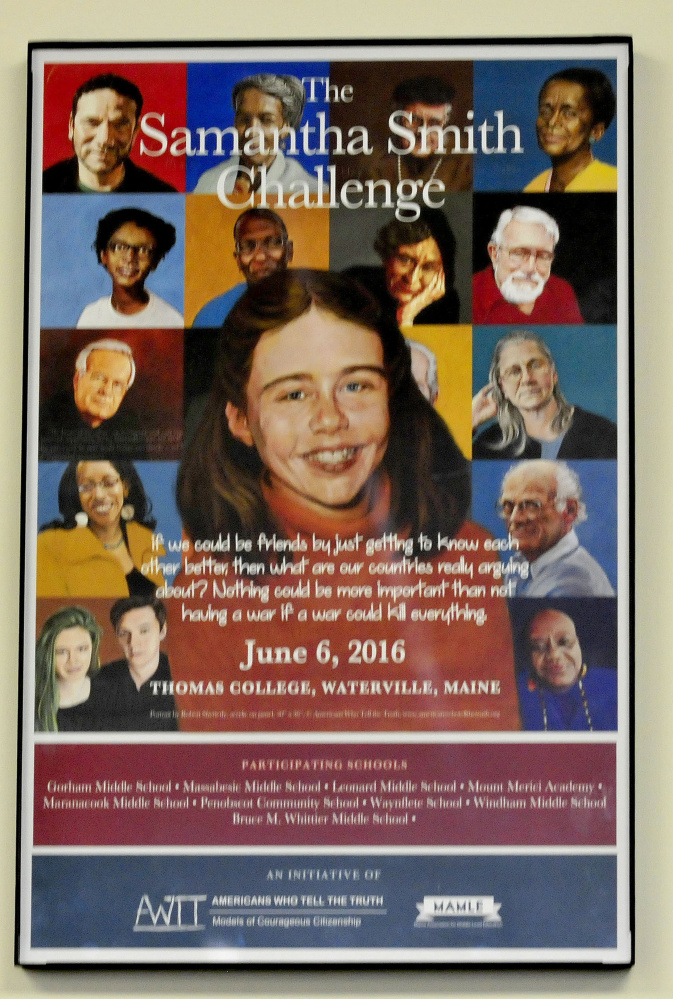

Ten of those portraits now hang on the walls in the college’s Center for Innovation in Education. Dr. Wally Alexander, a professor of education at Thomas, said Shetterly’s “Americans Who Tell the Truth” group had partnered with the Maine Association for Middle Level Education about two or three years ago, when Alexander was the executive director. That was the grounds for getting Shetterly’s work into the college.

The 10 portraits will rotate over time, and the ones in the college were mostly requested, and for now include such figures as Maine’s U.S. Sen. Margaret Chase Smith, U.S. first lady and U.S. Delegate to the United Nations Eleanor Roosevelt, journalist and activist Colman McCarthy and Maine resident Samantha Smith, a middle school student turned activist during the Cold War who died in a plane crash in 1985. Each portrait has a quote from the individual, which Shetterly said he found in his research of the individual.

“Everybody he paints has had significant influence on American society,” Alexander said.

Laurie Lachance, president of Thomas College, said while introducing Shetterly that the portraits had “added soul” to that wing of the building; and “given the tumultuous times” the country was in, the paintings can “center us.”

“For me, having these pieces of art in our hallway has been very, very moving,” Lachance said.

Shetterly said a major theme of his work was education, a message he stressed to his audience of student educators. He spoke of a female activist named Bree Newsome, who climbed a flagpole at the South Carolina State House to remove a Confederate flag that was atop it. She was arrested afterward, but eventually the state government voted to remove the flag from the State House. Shetterly said he had to paint Newsome because she had changed history.

“There are people making history all the time with their courage,” he said.

Shetterly spoke of the current presidential administration, again stressing the challenges of teaching it to future generations. He said Scott Pruitt, who was approved to head the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, is a person who “doesn’t believe in science and instead believes in the rights of corporations over the environment.”

The challenge, he said, was how to pursue happiness in a “toxic world.” One way to do that is to find the stories out there, as he’s tried to do with his portraits. Educators, he said, can find those stories and show them to their students. That’s important, he said, because children need to know what they’re capable of so they can enact change in the world.

“Being a teacher is not just a job,” he said. “It’s a sacred trust.”

Colin Ellis — 861-9253

cellis@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @colinoellis

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story