WATERVILLE — At the intersection of art, metaphor, addiction and community stands Michael Libby, who’s taking his message to the people.

On a bright but cold Thursday morning, he stood in Thomas College’s Ayotte Auditorium, where a week earlier his artwork had brought the community together for a discussion on drug addiction.

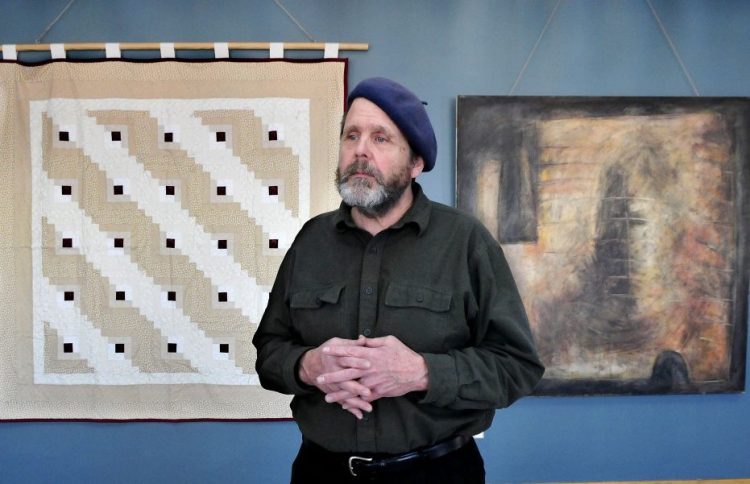

Libby, 58, a Waterville native who lives in Lewiston, is an artist as well as a certified alcohol and drug counselor, and in the spring expect to graduate from the University of Southern Maine with a master’s degree in psychiatric rehabilitation counseling. In Ayotte Auditorium, he stood before a section of an exhibit he has shown a handful of times in Portland and Lewiston. The exhibit at Thomas — which was taken down Thursday — is about addiction; but as Libby describes it, the display is also about personal loss, “saying goodbye and welcoming grief.”

“Art has a way of objectifying ideas,” he said.

And art can provoke strong public response. Libby plans to take his art to an even higher level, literally, with a 30-foot-tall hot air balloon shaped like the chemical compound of heroin.

Over the course of 20 years, Libby lost three of his four siblings to drug- or alcohol-related deaths. His brother Reno died of a heroin overdose in 1992. It was after that when Libby began walking. In Portland, he walked in parking lots, and eventually he began sketching parking lots. Later, he put the lots onto canvas, painting abstract images of bird’s-eye-views of the areas he walked.

“Part of my motivation is to learn about myself,” Libby said, “but the show is also about saying goodbye and welcoming grief.”

The Thomas display contained about a third of the entire exhibit, Libby said, with two parking lot images and a quilt he had made in 2013. In describing the quilt, Libby addressed what he saw as the real issue with addiction. Especially with the opioid epidemic in the state, he said, the real issue is a desire on the part of the user to solve an issue of alienation.

“Heroin isn’t killing people; loneliness is,” Libby said.

Libby’s quilt, which is titled “Opium: A Comforter,” is an expression of alienation and deep comfort, as he says comfort is one of the things someone is looking for when they turn to opioids. He said heroin creates a chemical sensation of love, and comfort is one of the main motivations for using it.

The quilt is a traditional log cabin design, referring to the pattern of the quilt. The colors on the quilt are all shades of different grades of heroin, he said, and there are red center squares stamped with harvested poppy pods. He said the quilt was also an effort to change the way people thought about heroin use and to better understand why someone would use it.

“My grief equals my love for these people I’ve lost,” he said.

Part of the work in creating the art was a desire to understand those feelings of alienation better and to try to find an answer for it. He said some kind of support needs to be provided to replace the chemical feelings of love and comfort created by heroin.

“We can all relate to loneliness,” he said.

MAKING CONNECTIONS

Libby said he wants to continue exhibiting his work, and he hopes at some point to do a five mill-town tour, with stops hopefully between Biddeford and Bangor. He said because he was from Waterville, he would want to include a stop in the Elm City along the way.

Libby said he wants to bring the exhibit to mill towns both because he’s from Waterville — where several manufacturing businesses have closed in recent decades — but because it seems like mill towns are hit harder by heroin problems. He said he doesn’t understand why that is, but there is a curiosity there. He said it could be something as simple as lack of employment, but it’s made him think about the relationship between mill towns and heroin use.

Mill towns in recent years have suffered major job loss, as once-lucrative mills shut down, putting employees out of work. According to a report by Maine State Epidemiological Outcomes Workgroup, the rates of overdose deaths are highest in Washington, Androscoggin, Cumberland, Kennebec and Somerset counties.

Meanwhile, Mainers are dying in record numbers because of drug overdoses, with 378 fatalities in 2016, a 40 percent increase over the 272 Mainers who died from overdoses in 2015.

Libby said he has spoken with Waterville’s arts commission about a public display, but any future plans would depend on securing funding.

Yet Libby said he wouldn’t want to set up a permanent location for his art, and he wouldn’t consider selling it. That’s because he considers the art more of a backdrop, a way to get people into a room and begin a community dialogue about the issues behind the art.

“Connecting with an audience and the public is really the motivation for the art,” he said.

During an exhibition, Libby said he typically does a 40-minute presentation on his art in a public venue, and then opens it up for a question-and-answer session. He said typically these sessions have gone on longer than the original presentation itself, as people would linger and keep the discussion going. He said it gives people a platform to tell their stories.

“I see art as backdrop for performance, for presentation, for dialogue,” he said.

Part of that dialogue involves a much larger project Libby wants to do. He wants to build a 30-foot-tall hot air balloon to fly over the mill towns. The balloon, which he designed as a poster with the title “Get High,” is shaped like the chemical compound of heroin. He said the balloon would provide a new perspective for the conversation.

“It’s a great metaphor for heroin use,” he said, as a hot air balloon is dangerous to use, and requires fire to take off.

He said something like this is “supposed to be a spectacle,” he said.

FULL CIRCLE

For Libby, being in Waterville was bringing things full circle. On a display at Ayotte Auditorium, the causes of each sibling’s death was listed below the sibling’s black-and-white photos. Reno died of a heroin overdose. His sister Sarah, died in a motorcycle accident, and his other brother, Matthew, overdosed on prescription drugs.

Now, years later, he said both his parents have died, so he only has one brother remaining. He created this very public way of saying goodbye in part because of how unexpectedly his siblings had died.

They didn’t say goodbye.

“Each time I present, I understand more clearly the message,” Libby said. “I’m saying goodbye to my family and welcoming the grief.”

Both of Libby’s future projects — the five mill-town tour and the hot air balloon that goes with it — hinge on funding. But he said it’s also contingent on the community. If there isn’t community support, he wouldn’t be compelled to force the projects on the towns.

“It’s not just my story. It’s a bigger story,” he said. “My goal was modest, to start a new dialogue.”

He said it’s difficult for professionals not to have the answers to addiction, or to be able to solve the problem with a magic pill. Addiction can take many forms, he said, but in a paradoxical way, these issues presented an opportunity to make the connections he speaks of.

Going forward, Libby said, he isn’t sure what exactly the future holds. He’ll graduate this May and will keep looking for funding for his tour. As for the hot air balloon, he likened it to his art.

It is meant to draw a crowd, and then begin the dialogue.

“This isn’t about the art,” he said.

Colin Ellis — 861-9253

cellis@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @colinoellis

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story