Whether it’s a 26,000-panel municipal solar array or just a few panels on the roof of a home, someone has to install solar systems for the lights to come on, and Kennebec Valley Community College in Fairfield is ramping up efforts to train these workers for the future.

KVCC offers two levels of solar photovoltaic training: an associate program and a design and installation program. Non-degree programs launched in 2012, they are designed for those already in the industry and are seeking certification from the North American Board of Certified Energy Practitioners.

The school formerly had a Solar Instructor Training Network, which was funded by the Department of Energy for a short time. The program opened its solar program to instructors from all over New England and New York and taught those involved about solar technology and how to teach those programs to future students.

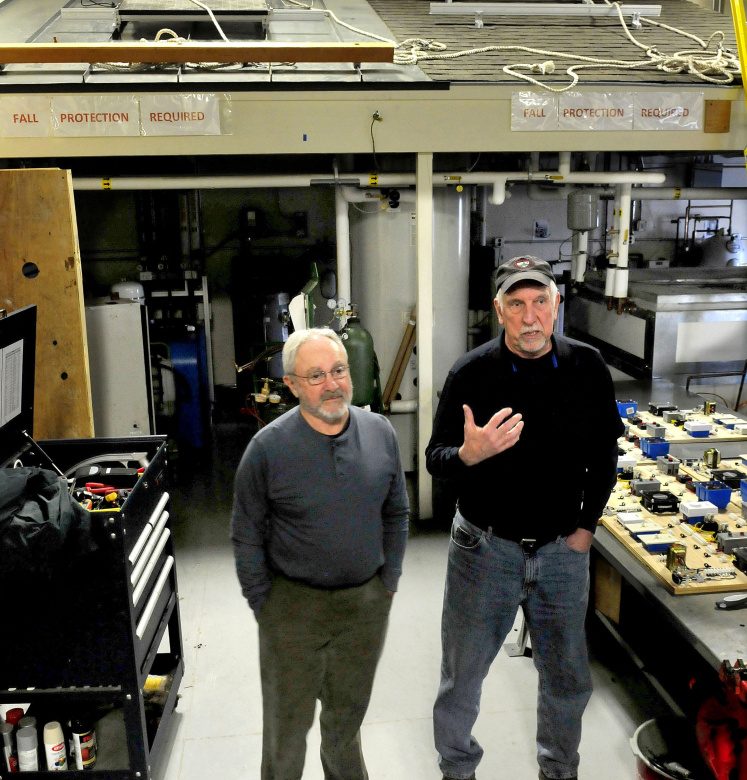

The design and installation programs give those enrolled a hands-on learning opportunity with a simulated roof and required safety precautions. Instructors Keven Vachon and Rich Roughgarden say the hope is to have KVCC become a center for this kind of training. As with most programs offered at the college, those who finish are expected to find employment fairly quickly.

“They will (get jobs), maybe not in Maine,” Roughgarden said. “The jobs have to grow locally if they want to stay here.”

That’s the big problem for the solar industry in central Maine: There’s the potential for future industry growth and jobs, but it’s still lagging behind — like the rest of Maine — in comparison to the rest of the Northeast. Industry experts say Maine’s incentives for solar creation are among the worst in New England, even if the actual prospects for solar projects in central Maine are bright.

Garvan Donegan, the senior economic development specialist for the Central Maine Growth Council in Waterville, said central Maine is well positioned to be a player in large scale solar projects going forward.

Donegan said central Maine has a number of things in its favor for solar in the future. He said there is a continued growth in the solar market that is tied to federal tax credits, which he expected to continue. Additionally, large tracts of land are available in this section of the state, as well as swaths of land near electrical substations.

“Central Maine does have strategic assets,” he said.

According to data from the Solar Foundation, which conducted a solar job census for 2016, the bulk of Maine’s solar jobs were located in Cumberland County. All told, there were 572 solar jobs in 2016, ranging from installation, manufacturing, sales and others. This included 242 new jobs since 2015, a 73 percent growth rate.

However, the number of jobs dipped considerably in more northern areas. For example, Somerset County reportedly had just eight jobs listed for 2016, and Franklin County reported just seven. Kennebec County faired comparatively better with 37 jobs.

The foundation, based in Washington, D.C., ranked Maine 40th in the country for solar jobs and 27th in solar jobs per capita.

Even so, central Maine is already home to the largest municipal solar array in Maine. The 26,000-panel array spanning roughly 22 acres in the Madison Business Gateway generates enough electricity to satisfy the needs of about 20 percent of Madison Electric Works customers. Superintendent Calvin Ames has said that on a sunny day, the farm will meet the needs of “100 percent” of the utility’s customers — about 3,000 homes and small businesses excluding Backyard Farms. The array was constructed by Ohio-based IGS Solar, and Madison Electric Works purchases all the energy it produces.

Two more large scale utilities are in the works in nearby towns. Fairfield and Clinton have been eyed for farms that would generate enough power for 6,000 out-of-state homes combined and create more than 200 jobs locally.

Ranger Solar, based in Yarmouth, is planning for the projects in Fairfield and Clinton to generate 20 megawatts of power each, and the generated power will be sold to Connecticut. The farms, the exact locations of which have not been released, are each expected to cost around $20 million. Before sites are finalized, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection needs to investigate the sites.

Ranger Solar is also planning to bring a utility-scale solar farm to Farmington that could break ground in 2018 and eclipse the size of any solar installation now operating in Maine.

The Madison solar farm is one of a handful of such projects being implemented across the state. The Oakland Planning Board approved a site application from Colby College to build a 1.9-megawatt installation with 5,505 solar panels on Washington Street with site work beginning in May. Bowdoin College has a 1.2-megawatt solar power complex in Brunswick. A Yarmouth company continues to move ahead with plans to build a 50-megawatt solar farm at the Sanford municipal airport. The Sanford City Council approved the lease in May 2016.

SOLAR ATTRACTION

Dan Eccher, an Oakland resident, said he installed solar panels on his home in 2016 and a solar hot water heater in 2014. He purchased them from Insource Renewables because he has always been environmentally aware and conscious.

“I’ve always been interested in alternative energy,” he said. “In recent years I have become increasingly concerned about global warming, and I wanted to reduce my personal carbon footprint.”

He said being able to sell his energy into the grid was one of the things that attracted him to solar energy in the first place.

The kind of projects Donegan has been involved with don’t go through the same state legislation process as smaller, residential projects. The larger municipal projects he has been a part of are largely results of funding by federal tax credits, which were extended by Congress in 2015. Because of that extension, construction of larger energy projects became more feasible, and there has been an upswing in these types of projects, specifically solar.

Vaughan Woodruff, president of Insource Renewables in Pittsfield, said utility scale projects involve a different kind of customer than residential projects. Since utility projects sell wholesale, the rules are different.

Steve Kahl, an associate professor of science at Thomas College in Waterville, said there are some misconceptions regarding solar projects. One major issue, he said, is the notion that it takes anywhere between 11 and 15 years to see a payback on the installations. He said that for some homeowners that may be a deterrent, as they might not envision being in that location for the next decade plus.

“It’s a 9 percent return (on the initial investment) for that 11-year period, then it’s free electricity for the next 40 years,” he said.

He likened the payback to pre-buying wood or oil for the winter, saying most people in Maine do those things, so they shouldn’t look at pre-buying electricity any differently.

“People have a 1970s mindset that solar is a fad and costs hundreds of thousands of dollars,” he said.

Eccher said generally he was seeing more solar projects pop up, which he said was a good thing, but he also wants to see more. He said he’s working with the Kennebec Montessori School in Fairfield, which his daughter attends, to get solar panels installed, maybe with a power purchasing agreement with a private company. Thomas College in Waterville entered into such an agreement with ReVision Energy in 2012. Thomas buys from ReVision the electricity the solar array on campus produces and will purchase the system from ReVision at a reduced rate.

“I’m hoping to arrange something like that for my daughter’s school and my church,” Eccher said.

INDUSTRY UNCERTAINTY

At KVCC in Fairfield, Solar Program Coordinator Robin Weeks said the new programs are geared toward certification and are the only ones she knows of in the state to offer design and installation. The associate program, which she said was about providing the fundamentals necessary for jobs in the solar field, is worth 18 educational credits. The design and installation program is worth 40 credits. In order to take the certification exam, a person needs those 58 credits.

Rich Roughgarden, an instructor, is an electrical engineer who started his own company, Maine Solar Engineering, in 2008. He said he took entry level classes towards certification at KVCC and eventually was certified. He and fellow instructor Keven Vachon run the design and installation program, a 40-hour program broken up over the course of two Friday and Saturday workshops with eight hours of the program done online. Vachon, a master electrician, said he came to KVCC after teaching electrical programs in Waterville and became an adjunct professor at the college a decade ago.

Vachon said they would like to bring solar programs into high schools to gauge interest early on.

Weeks said the former training network had a mobile mock roof setup that could be moved to different areas for lessons, something they would like to try again.

“We’re hoping to get a mobile unit back into service,” she said.

Weeks said that so far 161 people have gone through the non-degree solar technology program. She said the plan is to start a steering committee to see what the next steps for the program will be.

Roughgarden acknowledged that the uncertainty regarding future legislation makes planning for installers difficult. But, he said, even though Maine’s incentive climate for solar technology is the worst in New England, there are still local companies that hire. Diverse business plans, like companies selling heat pumps in addition to solar panels, help keep business going, he said, and the continued growth of solar in the state could have more of an impact on job creation.

Roughgarden said that in conversation with legislators, he and others try to make the case for solar energy being a business decision rather than a political debate.

“The trouble is if it becomes ideological,” he said.

Maine’s immediate solar future might appear a bit murky with policies that haven’t encouraged job growth in the industry. A portion of incentives for residential arrays is set to decrease beginning next year — though customers will continue to receive the full credit of their supply portion.

Woodruff said that on a smaller scale, the growth of solar projects in central Maine are similar to installation trends across the state. He said concerns about regulations may be spurring more people to rush to get solar panels on their homes and businesses now, as the financial return may not be as great in the future.

“Some folks are doing it because they wanted to make a statement,” he said. “Others felt now was the time to act.”

He added that the market right now was picking up before new rules went into effect.

SOLAR POLICIES

The state’s solar policy is governed by the Maine Public Utilities Commission, and a recent recommendation by the PUC could spell trouble in the future for homeowners and small businesses that would rely on incentives to switch to solar. Under the proposed rules, homeowners who have already installed solar panels would be compensated for the power they produce at a full retail rate for 15 years, but after the calendar hits 2018, those who install solar panels would see the credit gradually reduced over time.

Woodruff explained that under the current rules for net metering, a billing mechanism that credits solar energy system owners for the electricity they add to the grid, clients get a 1-1 credit. That means for every kilowatt hour exported to the grid, that client receives equal value credit back. Going forward, he said those values are set to decrease, first to a 90 percent credit, then to an 80 percent credit, and so on.

Kahl, the incoming chair of the Sustain Mid Maine Coalition energy team and the former director of energy and environmental strategies for Sewall Company in Old Town, said the decreasing value system is unacceptable. He said what the PUC has proposed is something completely in favor of the utilities and not in favor of individual homeowners. He likened it to someone planting a garden on their property, and then having a commission placing a tax on the vegetables produced in that private garden.

“It just doesn’t make sense,” Kahl said.

Woodruff said this proposal, in the short term, may mean more homeowners rush to get solar panels installed before the sunset of 2018 hits. After that, he said the pendulum will swing the other way. He called the proposal a “solarcoaster” that creates an arbitrary deadline for people who want to install solar panels to get the full benefits of them.

“Folks are looking to get in under the simple scenario where they get the full benefit of net metering,” he said.

John Reuthe, the former chair of the energy team at the Sustain Mid Maine Coalition, said that the more people have the installations put in will make it harder for the government to try to “get in the way” of the movement.

“It’s clean energy and we certainly need it,” said Reuthe, who was part of a group that worked to outfit the Quaker meeting house in Vassalboro with solar panels last year.

Kahl said despite political resistance, solar projects are moving forward everywhere in the country.

“Resistance in the state of Maine is going to put us behind the eight-ball,” he said.

Tom Tietenberg, a retired professor from Colby College in Waterville who said he has kept his eye on solar developments, said he sees solar penetration as “pretty much inevitable” with the prices of these technologies falling. He said all over the country, solar energy is “on parity or below parity” with fossil fuel generation.

“This industry is really thriving,” he said.

Colin Ellis — 861-9253

cellis@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @colinoellis

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.