In remembrance of D-Day, which marks its 73rd anniversary on Tuesday, I sat down and listened to audio tapes my father-in-law made years before he died at 98 in 2010.

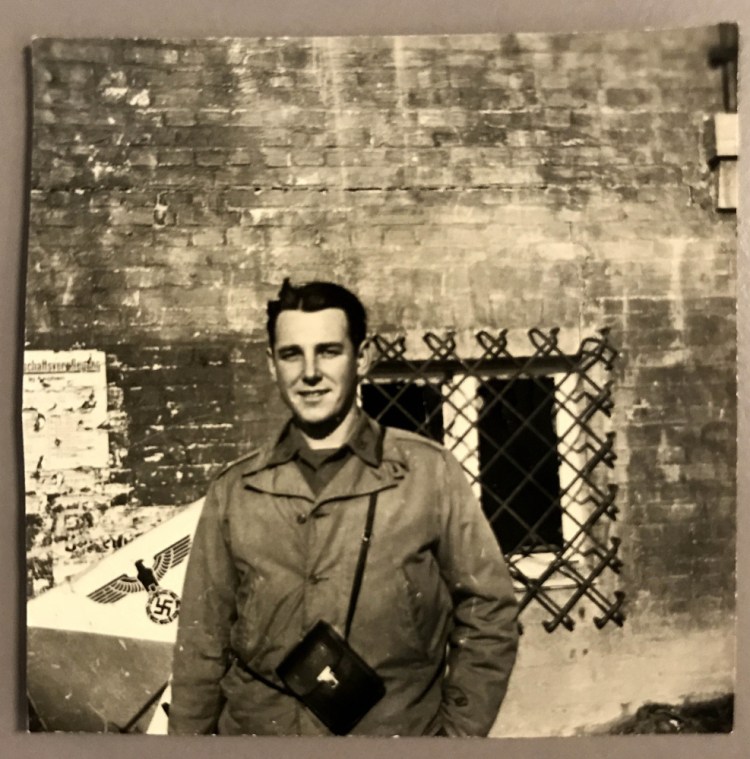

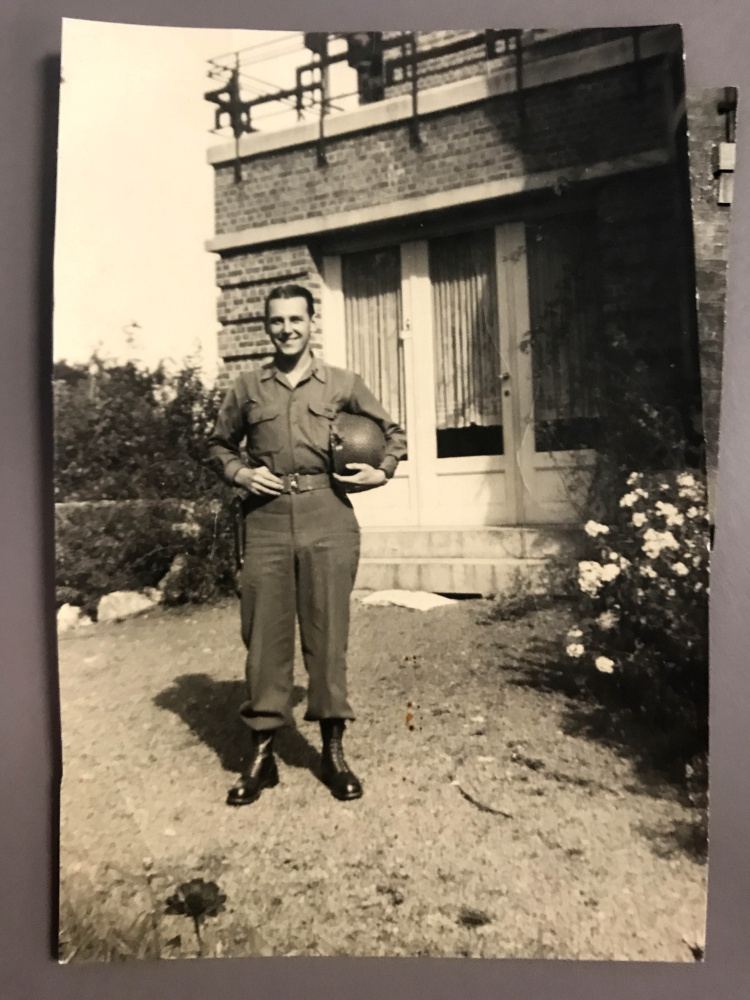

Franklin Norvish was an amazing man, really. From 1943 to 1945 during World War II, he served in the European Theater of Operations as a special agent in the Counter Intelligence Corps attached to the VII Corps. Commanded by Gen. “Lightning Joe” Collins, Frank’s unit stormed Utah Beach at Normandy June 6, 1944, with Frank driving a jeep. His friend, Mike, was in the passenger seat.

“I shoved it in low gear and shouted, ‘Here goes!'” Frank recounts in his audio narrative. “Mike shouted in my ear, ‘For God’s sake and the sake of sweet Jesus, don’t stall it.'”

Prior to crossing the English Channel to Normandy, Frank, Mike and the other men slept fitfully for three nights, huddled in sleeping bags on the hard stone streets near the Southampton docks.

“It was all a hideous, noisy nightmare,” Frank recalled.

The sky was filled with the droning planes of the Air Force, and the chaos and confusion were indescribable, he said. There were so many boats in the Channel, it was almost like a bridge one could walk across. Trying to get onto a landing craft was difficult, but they made it.

“The din and the turmoil and disorder was mind-boggling,” Frank said. “We were separated and herded aboard.”

The men were ordered below, packed like sardines.

“There was only one stairway up, and I could see the fear and panic in the eyes of all around me, and I knew if we were hit, there would be a stampede. We were bleary-eyed and tired and the rough waters and the noise didn’t help any. Soon we were passing U.S. Navy ships shelling targets on shore without let-up. The muzzle blast of cannons was ear-splitting. Four shots — bang-bang, bang-bang and then again, bang-bang, bang-bang. Incoming enemy artillery shells were exploding all around.”

After rolling down the ramp of the landing craft named Elihu Root and into the water, Frank was submerged up to his armpits. He forged onward through boxes, bags and bodies floating in the water. Once ashore, he and Mike opened the hood of the jeep and ripped away wax from the battery and carburetor as water poured out of the vehicle.

Several weeks later, Frank entered Paris with Gen. Charles de Gaulle’s entourage to liberate the city, which German troops had occupied since the fall of France in June 1940. Frank had been ordered earlier to memorize 75 names of collaborators, saboteurs, defectors and infiltrators. Later, Frank was instrumental in arresting those collaborators and was most proud of helping to locate and ship off to London six German nuclear scientists and their notes.

Fluent in several languages, Frank had graduated in 1934 from Colby College in Waterville and later Yale University. He taught English at Northeastern University before and after his military service for a total of 40 years. While serving in the military, he was awarded a Bronze Star.

He regaled us with stories of his life way into his 90s. He was a joy to be around.

After D-Day, his war experiences continued. In his tapes, he recalls being on the front lines on a hillside in Normandy where the men slept in pup tents 10 feet apart. Visiting Brigadier Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr., 57, the son of President Theodore Roosevelt, occupied the tent next to Frank.

“He said, ‘I hope it gets a little more quiet — I’d like to get some sleep,'” Frank recalled.

They bade each other good night, and around 5 a.m. the next day, Frank woke to a commotion outside. He looked out and men were carrying Roosevelt’s body away. He had died of a massive heart attack during the night. It was July 12, 1944.

Frank met generals George S. Patton and Dwight D. Eisenhower in his travels throughout Europe. In Germany, Frank became very ill with a fever and stopped at the cottage of an old German couple whose son-in-law had been killed in the war. They moved a cot next to the stove for Frank, gave him a glass of whiskey with a raw egg in it, and Frank fell off to sleep. He slept 12 hours and woke feeling refreshed and well.

“It’s hard to believe, isn’t it?” he says in the tape. “You’d think that war in general would mean everyone was at each other’s throats. Not so.”

Frank was one of the first to enter the grounds of the Nordhausen crematorium, where corpses were piled high like cord wood, he said. Men he described as walking skeletons approached him, weeping and begging for food. He gave them soda crackers he kept in his pockets, and they ate them but could not keep them down. Frank later was named commandant of the Leipzig jail.

He visited a small German hospital where a 17-year-old, displaced Lithuanian boy had lost both legs at the knee in a railroad accident. Frank gave him a gold watch and made telephone calls to a U.S. doctor who ordered prostheses for the boy. Years later, the now older amputee searched for Frank in the U.S. and found him at his home in Needham, Massachusetts. He walked stiffly up Frank’s driveway, tears in his eyes, and embraced him.

“He said he owed his life to me,” Frank recalled.

On July 1, 1945, after the war in Europe ended, Frank sailed back home to the U.S., landing in Newport, New Jersey, to live bands and flowers. Later, he went to California and then New York City, where he met Jimmy Durante. Durante bought him a soda.

“He patted me on the back and said, ‘We owe you.'”

At the end of his narrative, Frank says he made the tapes as a promise to his son, Phil, my husband.

We feel lucky to have them and to hear his voice — so clear and familiar — it seems as if he is sitting right next to us. His final words are heartfelt and apropos, as we approach the anniversary of D-Day:

“I never asked what my country could do for me; I did what I could for my country, and would do it again.”

Amy Calder has been a Morning Sentinel reporter for 29 years. Her column appears here Mondays. She may be reached at acalder@centralmaine.com. For previous Reporting Aside columns, go to centralmaine.com.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.