Donald Trump doesn’t spare much time for reading. “I never have,” he explains. “I’m always busy doing a lot.”

But what he is now busy doing is managing a global crisis with nuclear dimensions and historical precedents. One adviser, Sebastian Gorka, has said, “This is analogous to the Cuban missile crisis.” Which demonstrates how a little bedside reading might come in handy.

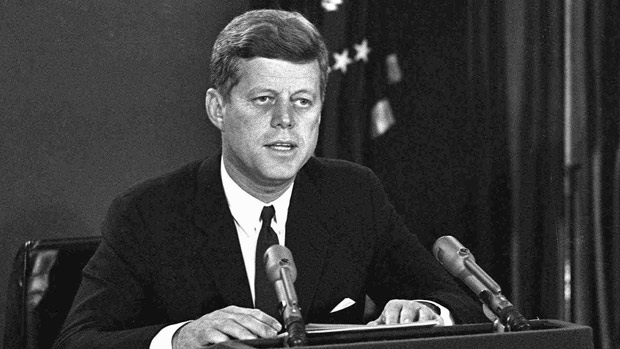

In his account of that 1962 nuclear standoff, “Thirteen Days,” Robert F. Kennedy describes a meeting with President John F. Kennedy early in the crisis. “A short time before,” recounts RFK, the president “had read Barbara Tuchman’s book ‘The Guns of August'” – a still-compelling account of the lead-up to World War I. “He talked,” RFK continues, “about the miscalculations of the Germans, the Russians, the Austrians, the French and the British. They somehow seemed to tumble into war, he said, through stupidity, individual idiosyncrasies, misunderstandings, and personal complexes of inferiority and grandeur.”

“I am not going to follow a course,” JFK later says, “which will allow anyone to write a comparable book about this time, ‘The Missiles of October.’ … If anyone is around to write after this, they are going to understand that we made every effort to find peace and every effort to give our adversary room to move.”

Is it possible to imagine our current president reading “The Guns of August” and applying its lessons to current events? By all indications, Trump lives in the eternal now of his own wants and compulsions. He combines a total ignorance of the past with a total confidence in his own instincts. Now, in the first crisis not of his own making, he must produce traits of leadership he has not exhibited before: judgment, prudence and wisdom. His default mindset is not only indifferent to these traits; it is antithetical to them.

Trump’s main virtue as president (and there are some) has been his choice of responsible, respected advisers on foreign and defense policy. The three generals — John Kelly as chief of staff, H.R. McMaster as national security adviser and James Mattis as defense secretary — are the real reasons Americans should sleep well at night, or at least sleep. And Secretary of State Rex Tillerson — though resented by his own demoralized department — is trying to be a calming influence.

But Trump has begun this chess game with a move taken from cage fighting – promising “fire and fury” if North Korea makes “any more threats to the United States.” This may be the flimsiest, most foolhardy red line in presidential history. The North Koreans – with a threat to Guam – crossed the line immediately, without consequence. Trump’s statement, made after days of briefings with advisers who surely urged pacific rhetoric, is perhaps best interpreted as a declaration of independence from those advisers themselves. It may have been Trump throwing off the resented constraints of sound counsel.

Ultimately, the most consequential event in the current crisis will take place between the president’s ears. He must decide if a North Korea with nuclear-tipped ICBMs is acceptable or not. Yes or no.

A case can be made for both sides. In one view, the North Korean regime is a criminal enterprise, not a suicidal death cult. The logic and practice of nuclear deterrence – which includes the right of a pre-emptive nuclear first strike – will hold. In another view, the North Korean regime is deeply unstable, prone to miscalculation and capable of unthinkable horrors. With the artificial confidence of nuclear capabilities, North Korea could blunder past real red lines and set off unpredictable escalation.

This is the decision we are trusting Trump to make – a choice that will determine policy at every stage of the standoff. And what will inform that decision? The instincts of an untested leader? The deal-making experience of the New York real estate market? The collective wisdom of military leadership?

During the 1962 crisis, President Kennedy determined that the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba was unacceptable. But he consistently pushed back against the advice of military action and probed its assumptions. In the end, he pursued a nonnegotiable objective with maximal diplomatic flexibility.

“Above all,” he later said, “while defending our own vital interests, nuclear powers must avert those confrontations which bring an adversary to the choice of either a humiliating defeat or a nuclear war.”

What Trump may need most at this moment is a geography lesson. The White House library is in the basement, right next to the main stairs.

Michael Gerson is a columnist for The Washington Post.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.