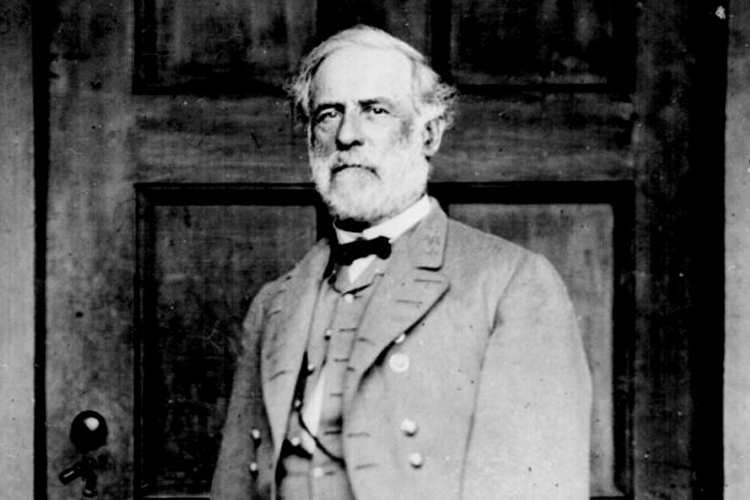

As our country lurches further into madness, one of the more depressing side effects is the denunciation of Robert E. Lee.

By the oversimplified, politically correct standards of today’s history, Lee fought for slavery and was a traitor to his country. Therefore his statues should come down, or be defaced, and his name dishonored. End of story. He did indeed fight for the side that sought to preserve slavery, and he broke the oath that he took when a cadet at West Point to defend the Constitution.

But the man and his life are far more complicated. No one can do them justice in so short a space as this, but I can give you at least some idea of what he was, and it’s better than keeping quiet.

Lee, like most Americans of his time, thought of himself as a citizen of a state first, and as an American second. He was a Virginian, and had he accepted command of the Federal Army, he would have been obliged to invade his home state and kill his neighbors and his family if they wore gray uniforms. This was more than he could do. It was more than most Union officers from the South could do.

Lee never complained, but how he felt about breaking his oath was probably expressed by another Confederate general named Lewis Armistead who, like Lee, had served in the Federal Army before the war. There, he was as close as a brother to an officer named Winfield Scott Hancock who commanded a corps for the Union at Gettysburg.

As luck would have it, Armistead led a charge against Hancock’s corps, and was fatally wounded. Dying, he asked that a message be taken to Hancock.

“Say to General Hancock for me that I have done him, and all of you, a grevious injury, for which I shall always regret.”

Maybe he said those exact words, or perhaps he simply gasped how sorry he was. My guess is that a great many Confederate officers who left the Union felt that way, and that Robert Edward Lee was among them.

Lee fought without hate. He called Union soldiers “those people,” and prayed for them every night. When one of his generals said he wished all Yankees dead, Lee said he wished they were all home, tending to their business, and leaving Southerners to tend to theirs.

At the end of the war, Lee had to choose between surrender and disbanding his ragged, starving, exhausted army to fight as guerrillas. He called a council of war and asked what he should do. One officer proposed surrender.

Horrified, Lee said, “But what would the country say?”

“My God,” said the officer, “there has been no country for a year and a half. You are their country.”

Lee chose surrender. He went to Appomattox Courthouse to meet Grant, and there the two generals acted as nobly as any American soldiers ever have.

Lee did not own a sword to present to General Grant as a token of surrender. He had to borrow one. Grant declined to accept it.

After the war, Lee was destitute. The Lee plantation, Arlington, had been seized by the Union Army and converted to the cemetery it remains today. His wife was an invalid. He himself was exhausted and sick with the heart disease that would kill him in 1870 at the age of 63.

He was offered $50,000 a year — a fortune at the time — by an insurance company for the use of his name. He declined, saying he could not accept money for work which was not rendered.

He did accept the presidency of Washington College. It was small and impoverished, but Lee, who had been superintendent of West Point and knew something of education, worked miracles. Today it is Washington and Lee University, and is one of the finest small colleges in the United States.

When one of his students, a Confederate veteran, denounced General Grant, Lee offered, very politely, to expel him if he ever heard another word of it.

Toward the end of his life, he said that “taking a military education” had been the greatest mistake he ever made.

He refused to write his memoirs, believing it would be making money from the blood of his soldiers.

No American general, and particularly no losing American general, has been so beloved by his men.

David E. Petzal of Cumberland is the rifles editor for Field and Stream magazine.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.