ORANGE, Texas – The storm once known as Hurricane Harvey made its second landfall Wednesday, dumping record rains and spurring additional flooding in small Texas cities east of now-devastated Houston.

Harvey, which had swung out into the Gulf of Mexico again, came ashore at dawn near the Texas-Louisiana border. Its rain bands preceded it, pounding Texas towns including Orange, Port Arthur and Beaumont with more than 2 feet.

City officials said much of Port Arthur – a city of 55,000 – was under water. A shelter for flood victims flooded. One official estimated that water had entered one-third of the city’s buildings.

“We need boats. We need large trucks, and we need generators,” said Tiffany Hamilton, a former city council member in Port Arthur who was helping to coordinate relief efforts in a city that also is without electricity. “The entire city has been flooded.”

About 80 miles to the west, the Houston area was just beginning to recover from the biggest rainstorm ever recorded in the continental United States.

Nearly 35,000 people were in shelters. Thousands of homes were still submerged. At least 37 people were dead, and that number was climbing as water receded, revealing the storm’s awful toll.

In Harris County, which includes Houston, authorities finally found a van, containing six members of a family, that had been washed off the road days earlier. All six people were dead.

A few miles away, authorities discovered the bodies of two friends who had gone out in a boat Monday, trying to rescue neighbors. They lost control in the current, and drifted toward the sparks of a downed power line. They jumped in, to avoid the current. The electricity was in the water, too.

Three other men, including two journalists from a British newspaper, suffered electrical burns but survived by clinging to a tree above the water.

On Wednesday afternoon, Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo said 20 people remained missing in the city. At one point, that figure was as high as 47, but Acevedo said 27 people had been found alive and removed from the list.

By Wednesday afternoon, the remnants of Harvey had moved into Louisiana, traveling at 8 mph to the northeast. Its peak winds decreased to about 40 mph and the storm was downgraded to a tropical depression Wednesday night.

Louisiana officials, who had worried that Harvey might devastate their state as well, said the threat of flooding appeared to be lessening.

“Somewhere between being complacent and being panicked is the right place” to be, said Gov. John Bel Edwards. “That’s where we’re going to ask the people of Louisiana to settle.”

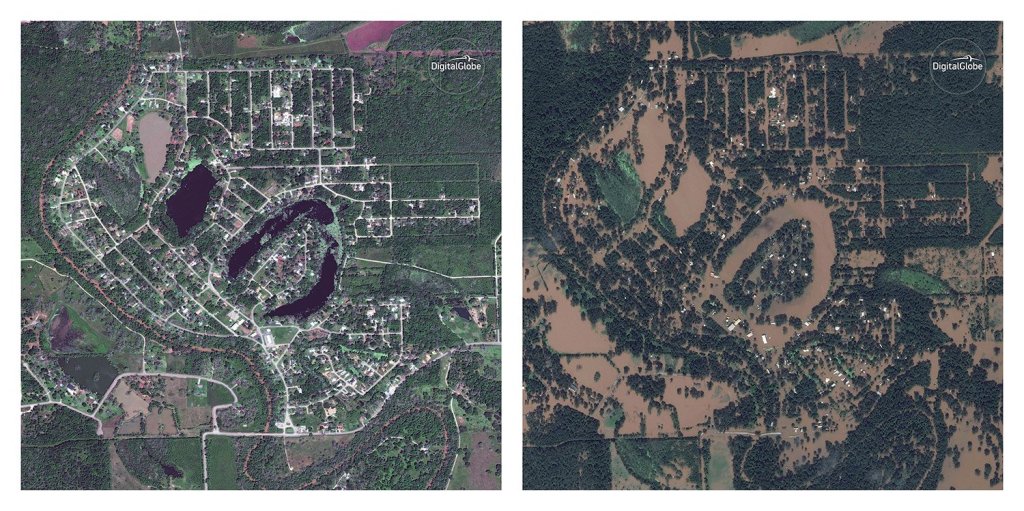

More than 50 inches of rain fell onto Houston over four days, turning the country’s fourth-largest city into a sea of muddy brown water, boats skimming along what had been neighborhood streets in search of survivors.

At the height of the flooding, between 25 and 30 percent of Harris County – home to 4.5 million people in Houston and its near suburbs – was flooded Tuesday afternoon, said Jeff Lindner, a meteorologist with the Harris County Flood Control District. That is an area as large as New York City and Chicago combined.

More than 210,000 people have registered for federal assistance, a number that is expected to increase, said Texas Gov. Greg Abbott. William B. “Brock” Long, administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, said it will take “many, many years” before the full scope of Harvey’s effect is clear.

Video: Stormwater floods nursing home in Port Arthur, Texas

Elaine Duke, the acting homeland security secretary, said at the same briefing Wednesday: “We expect a many-year recovery in Texas, and the federal government is in this for the long haul.”

President Trump has pledged swift federal aid in response to Harvey’s devastation. On Wednesday, Abbott said that given the sheer number of people and the geographic area affected, he expects the government’s aid package “should be far in excess” of the roughly $120 billion allotted for Gulf Coast recovery after Hurricane Katrina.

Trump could request emergency funding as soon as next week, a senior administration official said, reshuffling the political agenda as the White House scrambles to deal with the storm’s aftermath.

The funding package is expected to be only a partial down payment and serve in part to backstop depleted reserves that FEMA had to respond to disasters.

No final decision about the funding has been made, and the amount could fluctuate based on conversations with lawmakers. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, said the aid package request could be as much as $200 billion.

Tens of thousands of Houston-area residents were living in shelters as they waited out the storm. After the George R. Brown Convention Center took on nearly 10,000 evacuees, a county official asked to use the NRG Center south of downtown.

A map of Southeast Texas and Louisiana shows rainfall levels and locates Orange, Tex.

“They called up our CEO yesterday, and said: ‘Hey, we need you to do the shelter,’ ” said Frederick Goodall, director of marketing for the nonprofit Baker-Ripley Neighborhood Center.

That call was Tuesday morning. By the same time Wednesday, the NRG Center was lined with cots and thousands of volunteers. By the afternoon, 900 people had been bused in from other shelters, and nearly twice that many were expected to arrive by the end of the day. Six days after the storm first made landfall, residents were still unsure how long they would be out of their homes or what they would find when the waters receded.

Some of Houston’s bayous began to retreat inside their banks – although Buffalo Bayou, Houston’s main river, was still rising in some sections because of the release of water from upstream reservoirs.

“The watersheds are falling, and while most of them remain well over their levels, and some remain at record levels, the water levels are going down,” Lindner said. But he cautioned that some homes already under water may “degrade.”

Across Texas, the storm shut down 11 oil refineries and curtailed production at nine others, while causing damage that led to at least 45 releases of harmful chemicals. In Crosby, Texas, a chemical plant was in critical condition after flooding disabled its refrigeration system and two backup power generators, raising the likelihood that the volatile chemicals usually kept at cool temperatures on the site would warm up and catch fire or explode.

Arkema, a French-based maker of organic peroxides used in plastics, pharmaceuticals and construction materials, removed all employees from the plant. Harris County police were scrambling to keep people at a distance; local media outlets said the evacuation zone had a 1 1/2-mile radius.

“We have lost critical refrigeration of the materials on site that could now explode and cause a subsequent intense fire,” said Richard Rowe, the chief executive of Arkema’s North American division. “The high water and lack of power leave us with no way to prevent it.”

Elsewhere, it was the first day of the rest of Houston’s history, where millions of lives had been reshaped and burdened by the flood’s destruction.

Cleanup doesn’t begin to describe what’s next.

Electricity was out. Debris littered the city. When a house caught fire in West Houston, firefighters couldn’t get water pressure to fill their hoses. Instead, they turned to the water around them and used a jet boat engine. They pointed the back of the boat toward the house, fired up the engine, and sprayed a massive water stream toward the blaze.

On highways that allowed for some traffic, large pickup trucks – some outfitted with monster truck-style tires – hauling boats made up the majority of the traffic. Grocery stores, doughnut shops and Mexican-food restaurants reopened.

For those lucky enough not to be in a shelter, it was a day to take stock of what Harvey left behind.

“I feel like I’m dreaming,” said Julie Steptoe, who ventured Wednesday morning to an intersection in Kingwood, north of Houston. Never taking her eyes off the water that engulfed the area, she continued: “I don’t know what to think. I’m hoping it turns out OK for everyone.”

In Katy, people offered gifts to the “Cajun Navy” volunteers from Louisiana, who had been conducting rescues in the area west of the city. What gifts does one give after a flood? Chewing tobacco. Bottles of water. Packs of dry socks.

Neighbors then turned to start the enormous task of removing water and waterlogged debris.

At the Ehlert house, China chests filled with Christmas village ornaments, computers, sweaters and silverware were stacked in the center of the living room. A grandfather clock was flooded. Floral wallpaper was peeling. Neighbors were lugging out trash and soggy drywall and insulation.

“Our neighborhood army is here – pizza and tools,” said Don Ehlert, 69, who lives in the house with his wife, Cheri, and two grandchildren, who are 5 and 12. After a call for help on a social media app, 50 people had shown up. Ehlert had never met most of them.

“This is what America is all about,” Cheri said.

Farther east, in Port Arthur and Beaumont, the rain was so bad that it sounded like hail on windows. Hamilton, the former council member in Port Arthur, said that in the rain, emergency lines were overwhelmed, and friends called friends for help.

“There are some who might want to take advantage of this situation, so even before it gets a foothold in the city, we just need to hold things in check,” Turner said at a news conference.

Hamilton said one of her friends got a call about 2 a.m. from an elderly woman.

“She and her husband were both in the water and he was in a wheelchair, and she said she was struggling to hold his head above water,” said Hamilton, who was finally able to relay the information to emergency workers about 10 a.m. Hamilton does not know if anyone was able to reach the couple.

In nearby Orange, the water began rising at 3 a.m. Wednesday, covering first the streets, then the small residential lawns. And by morning, it was rising faster, pushing into homes and submerging to the rooflines of cars, trapping hundreds of people in their homes.

“It was unbelievable,” said Robin Clark, who was ferried, along with her mom – who uses a wheelchair – and three dogs, out of her home on a volunteer’s john boat.

Dozens of rescued residents stood in a pelting rain outside a Market Basket supermarket.

They were saved. But being saved was just the start.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen,” said Keeleigh Amodeo, 15, who was waiting with her sister and mother.

1 trillion gallons of rainfall has fallen in Harris County over 4 days which would run Niagra Falls for 15 days #houwx #houwx #txwx #harvey

— Jeff Lindner (@JeffLindner1) August 29, 2017

Speaking in Missouri on Wednesday, Trump praised the first responders and local officials for their handling of the storm. Trump also made a point of talking about victims of the storm and their suffering, something he did not do during his trip to Texas a day earlier.

Around Houston and beyond, schools and universities were closed, with some unable to say when they would reopen. The storm had pushed water to spill over in reservoirs west of downtown Houston, raising fears that the overflow would eventually make its way to the soaked downtown.

But officials said Wednesday that was unlikely. Lindner, the Harris County flood control meteorologist, said the reservoirs had stabilized and authorities were more optimistic that significant water would not make its way downtown. The Army Corps of Engineers and Houston flood-control officials said at a news conference Wednesday water-levels in city’s bayous and reservoirs were peaking and new flooding citywide should be less than initially feared.

About 250 miles to the north, Dallas was preparing to take at least 6,000 evacuees from the Houston area, according to Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins, the county’s top official. There were showers. Phone-charging stations. There was a dining hall manned by volunteers, including the Texas Baptist Men and local Israeli-American and Muslim-American groups.

The Dallas shelter was still mostly empty on Tuesday because the storm was too bad to get evacuees out of Houston.

“The planes are grounded, so we can’t get C-130s in” with evacuees, said Jenkins. “The roads are covered with water, so we can’t get buses in.”

Dallas housed 28,000 evacuees after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Jenkins said. He said he’s not sure if that many will come this time.

“We don’t know what we’ll get,” he said, “until the water recedes.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.