In the town of Clinton, bridging the language barrier takes patience and understanding on both sides.

The small department of six officers doesn’t have room in its budget — just over $240,000 in 2016 — to hire a full-time interpreter or to contract with LanguageLine Solutions, a translating service that is used widely throughout Maine and nearly 3,000 other public safety agencies in the United States and beyond.

Senior Officer Karl Roy estimates the police responded to about five calls that involved a language barrier last year. While not a high number, it reflects the number of migrants who are moving to the “dairy capital” of the state to work on the farms.

About 1 percent of the population in Clinton was Hispanic or Latino in 2000, according to U.S. Census data. By 2010, that rose slightly to 1.1 percent — an increase of about eight people in the town of 3,500.

While Maine is still the whitest state in the U.S., the diversity of its population is increasing slowly but steadily, as evidenced by its immigrant population. From 2000 to 2010, the number of immigrants moving to Maine increased by about 20 percent, according to Susan Roche, executive director of the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project in Portland.

“As the years go by, we’re becoming more of a melting pot,” Roy said, “and it is getting more difficult” for police.

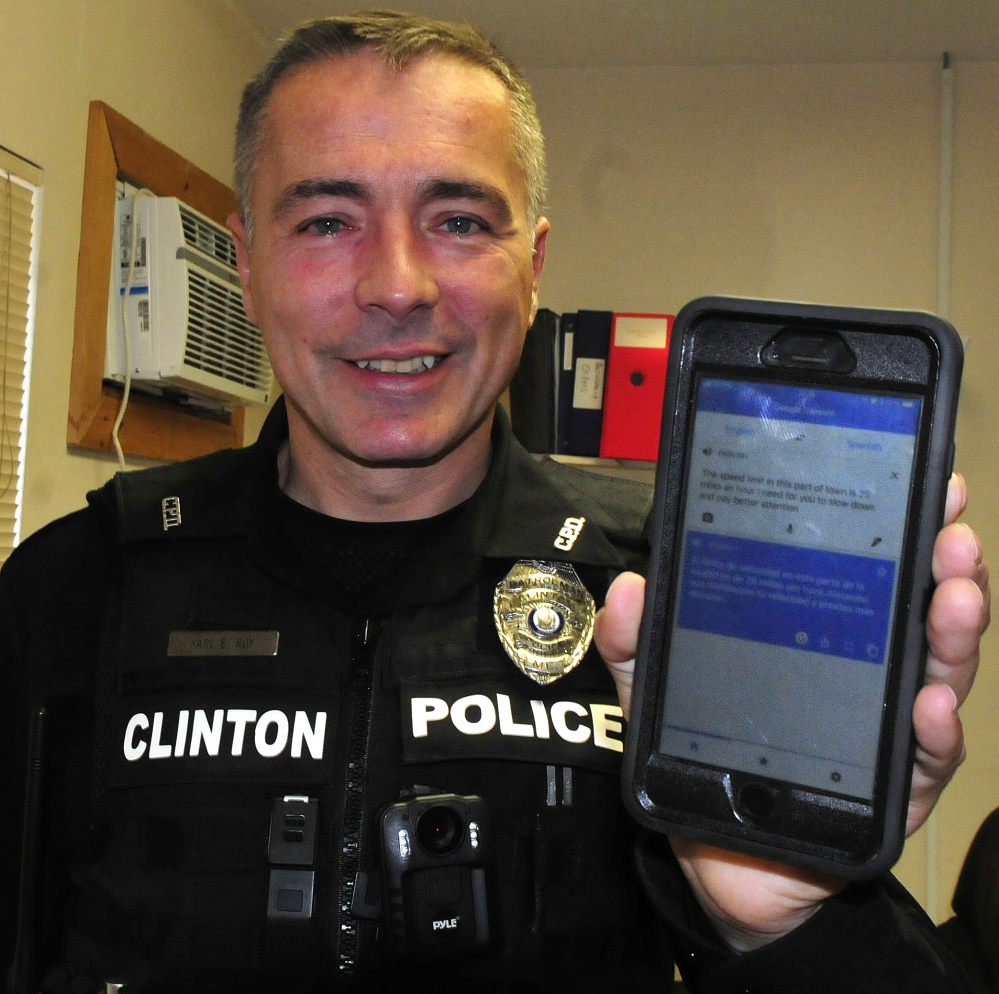

For a small-town department, raising extra money to assist with language translation can be a tough task. So Roy has found ways to communicate with non-English speakers for free. Sometimes, he uses Google Translate on his phone to speak with Spanish-speaking Clinton residents, although that can lead to miscommunication.

“Usually when there’s a misunderstanding, both of us end up laughing,” Roy said.

For that reason, Roche said, using Google Translate isn’t an effective way to communicate with someone. “It’s not perfect,” Roche said, and it often doesn’t catch the nuance of a foreign language.

While Roche said she understands smaller departments have limited resources, people who are talking with police have a right to due process.

“Even if it’s not a criminal matter, if it’s anything the police are dealing with, it’s important to have an interpreter,” she said.

The department also enlists the help of a volunteer based in Connecticut as much as possible, Roy said. A Spanish-speaking woman whom Roy knows as May had been used as a interpreter in a case, and she offered to help the police further when she is available.

The officer will hand the phone back and forth with the person he or she are talking to, speaking to the woman in Connecticut.

“It reduces efficiency,” Roy said, but added that it helps the officer and the resident understand each other.

Maine police officers aren’t required to learn another language, but they do take a class on cultural diversity and they are taught about language services in tandem with classes on search warrants and interrogation strategies.

The Maine Criminal Justice Academy also has officers work with people who are hearing-impaired.

“It can be something as simple as handing them a piece of paper and having them write a note,” said John Rogers, director of the academy.

The class on cultural diversity aims to teach officers about culture and how it relates to policing and the community, as well as what communication techniques are effective for different people in a community.

Roy said he wishes there was easier access to some of the tools used across the state, such as the LanguageLine, the go-to option for many mid-size and large departments and Maine State Police dispatchers.

While he doesn’t think the state necessarily should fund the service for smaller departments, it would be helpful to provide access for smaller departments to buy into the services.

SPEAKING OUT

LanguageLine Solutions uses method to communicate that is similar to that of Google Translate. The officer will identify what language is needed and call the LanguageLine, which then will connect the officer with the correct interpreter, who will interpret into both English and the foreign language. The service offers interpreters in 240 languages.

Often cities will contract with LanguageLine so that all departments can have the communication tool. Augusta, for example, has a citywide contract.

The company agrees on a per-minute rate with departments, which then pay as they use the service, according to Scott Brown, the content manager at LanguageLine Solutions. It does not require contracts of a certain size.

The Augusta Police Department uses the service for information, though police hire contract interpreters through Pine Tree Legal Assistance for criminal matters, Deputy Chief Jared Mills said.

Mills said he has been involved in situations that used three different ways of communication. For “minor situations” in which he just needs to explain something to a non-English speaker, he occasionally uses a family member to interpret.

Roche and other police chiefs also said that family members should be used for interpreting only if necessary.

“Sometimes there might be an emergency situation where you have to use whatever is there,” she said, but otherwise it’s best to use an impartial professional, rather than a family member who might be embroiled in the situation. Roche also said police never should use children, no matter what the situation is.

When Mills is dealing with a crime, he calls the LanguageLine, enters the department’s number code and finds the appropriate language. In some instances, the non-English speaker will call an interpreting service, which will call the police to begin the three-way conversation.

In recent years, the department’s expenditures for communication services have been increasing. In fiscal year 2016, it paid $13 for the LanguageLine. In fiscal year 2017, it paid $25 for the LanguageLine and $400 for contract interpreters through Pine Tree Legal. So far in fiscal year 2018, it has paid $7 for the LanguageLine and $562 for interpreters.

The number of incidents, however, has stayed relatively steady. The number went from one in fiscal year 2016, to three in fiscal year 2017, to two so far in fiscal year 2018, out of the approximately 50,000 calls the department handles annually. The number does not reflect times when a family member or resident was used to interpret for officers, however.

The department always has had a budget line for these kinds of services, Mills said, which also can include interpreters to speak with the hearing-impaired. But he understands how smaller towns might have trouble adjusting to a change in demographics.

“When the money’s not budgeted, … that can be a struggle,” he said.

WORKFORCE DIVERSITY

Still, Mills hopes to hire someone one day who is multilingual and reflects the changing demographics of Augusta, which has received an influx of Iraqi and some Syrian refugees who often speak Arabic as their first language.

His wife, Vivian Mills, is Arabic and works as a nurse at MaineGeneral Medical Center in Augusta. She often helps interpret for non-English speakers seeking medical help.

For now, though, police said it’s hard to reach those goals.

“It’s difficult to recruit now, period,” Michael Sauschuck, chief of the Portland Police Department, said. “The long-term goal is we want to mirror the community we serve, so I’m always looking to diversify the workforce.”

For now, less than 5 percent of the Portland Police Department staff are people of color, while more than 15 percent of Portland’s population are people of color, Sauschuck said. The department works to get to know residents through community policing, he said, so they can get a cultural understanding of who they are and what situation they are coming from.

“There’s a lot of cultures. There’s a lot of different angles,” he said. “We’re not going to be experts on everything, but we want to learn everything we can.”

Brian O’Malley, Lewiston’s police chief, said his department also tries to recruit some of the immigrants, mostly Somalis, in their city.

“We would like to have a more diverse police force to better represent our community,” O’Malley said. “My hope is that in a few more years, those kids will graduate school and go to college and get an associate’s or bachelor’s degree and come back and go to the police force.”

For more than 15 years, the city has had a contract with the LanguageLine, which has “been a benefit to us,” O’Malley said. When he first started at the department, the service was used with elderly people who were more comfortable speaking in French.

While there are communities with rising immigrant populations throughout the state, police don’t yet need full-time interpreters, they said. But Roche said she expects the need will increase as more immigrants come to Maine.

While some have English language skills, they might not yet be comfortable enough with the language to use it with police, “when somebody’s nervous and they’re discussing very important, very complex stuff,” she said.

“I think it’s important, and it can be a constitutional issue as well,” Roche said. “It’s really an important investment to ensure public safety.”

In Clinton, Roy hasn’t run into a situation so severe that where Google Translate or calling an out-of-state translator would be too slow, and Roy hopes his department never does.

For now, he said that half the battle is how you approach someone.

“If you approach them with a smile on your face, 50 percent of the difficulty in communicating is over.”

Madeline St. Amour — 861-9239

mstamour@centralmaine.com

Twitter: @madelinestamour

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story