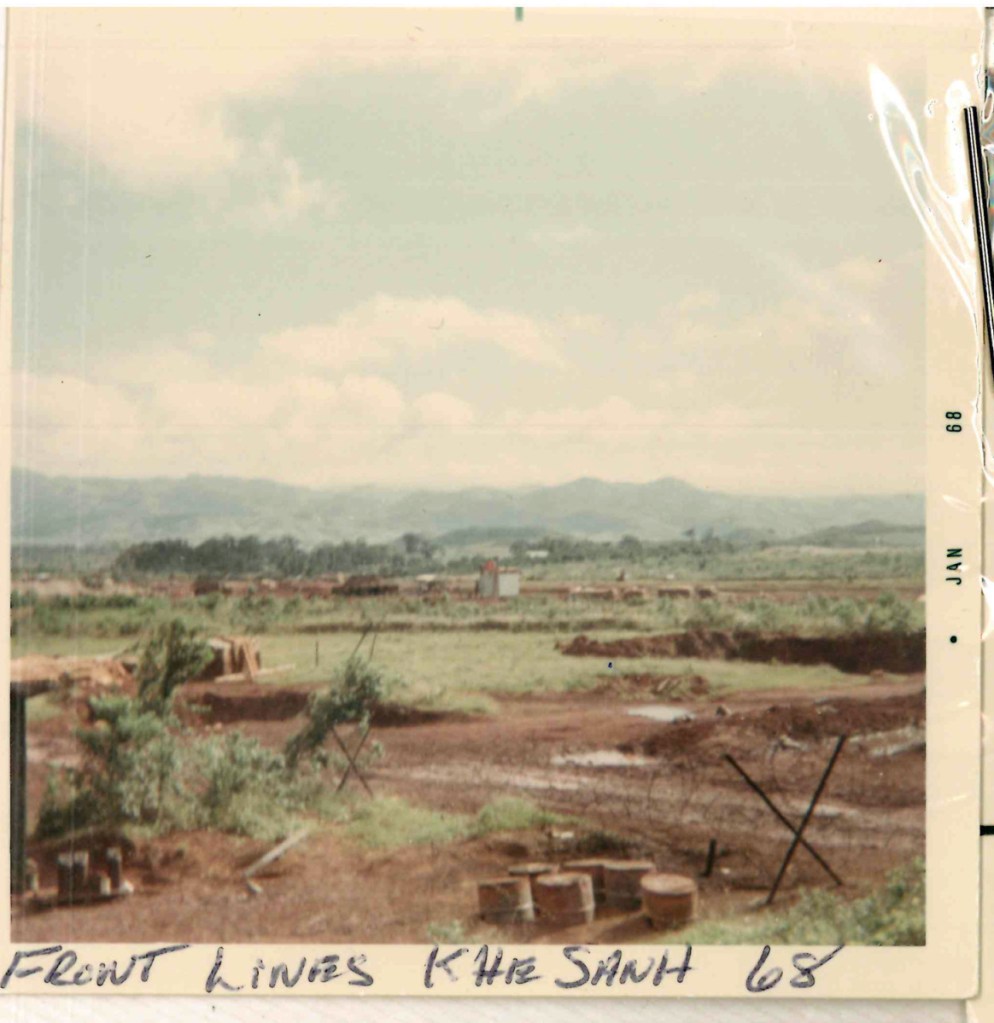

Ralph Sargent swears he felt the 152-millimeter artillery round fly by as he crouched in his foxhole dug into the red clay of Khe Sanh, South Vietnam, narrowly missing him and hitting a pallet about 10 feet away, peppering the Marine with splinters but leaving him otherwise uninjured.

It was one of numerous close calls in Vietnam for Sargent, now 82, of Augusta.

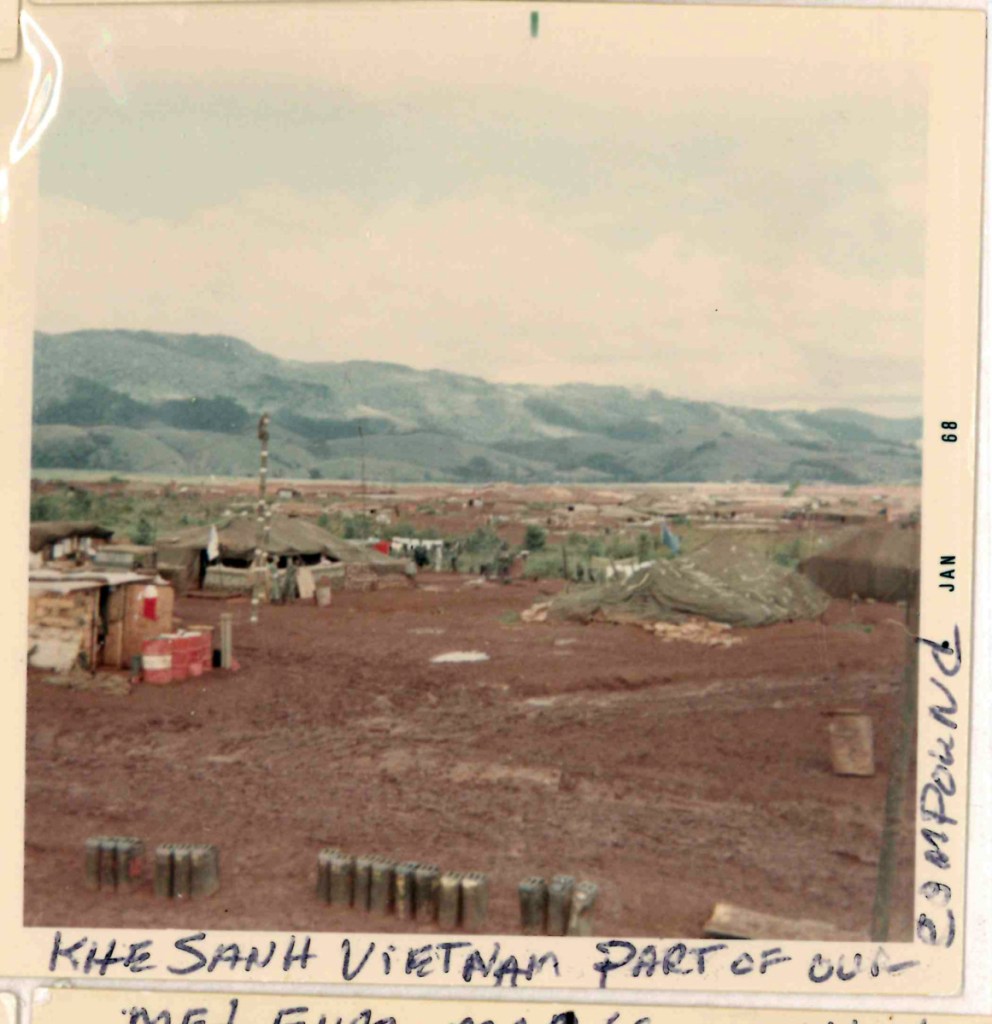

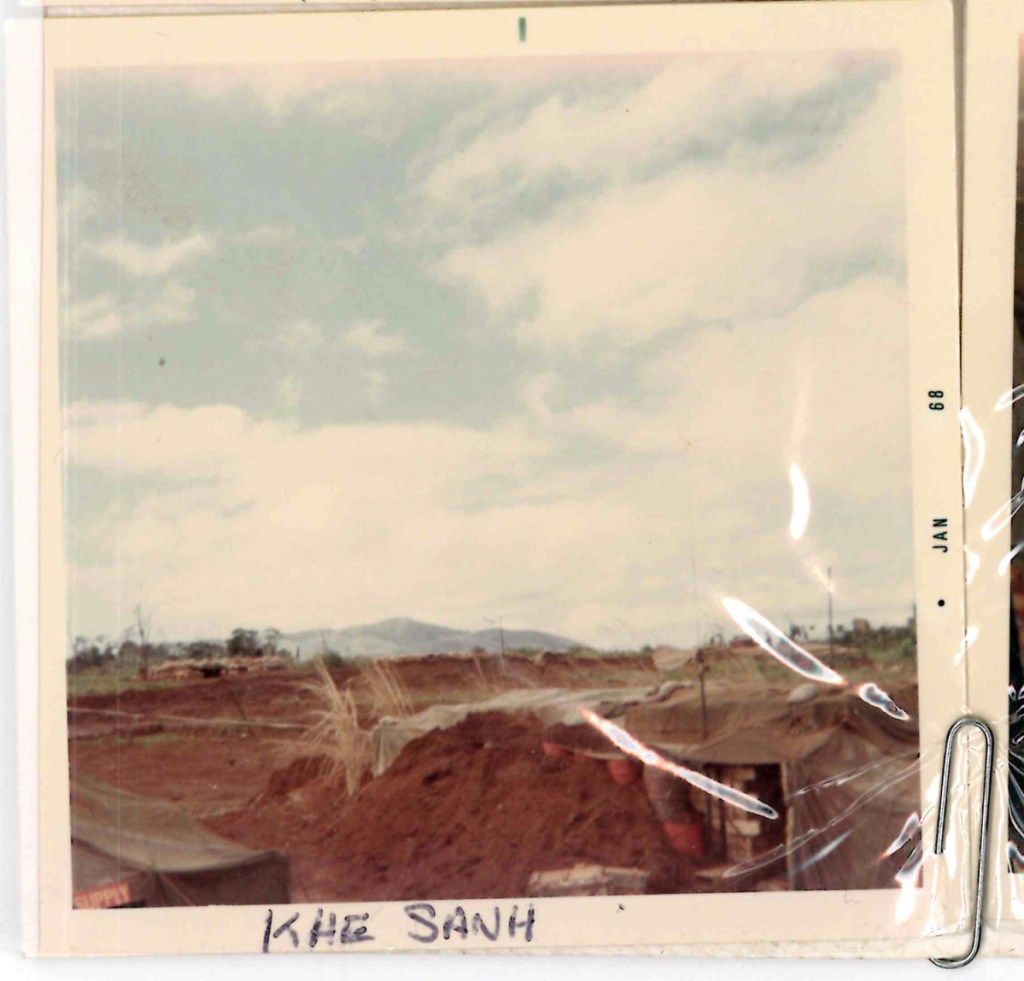

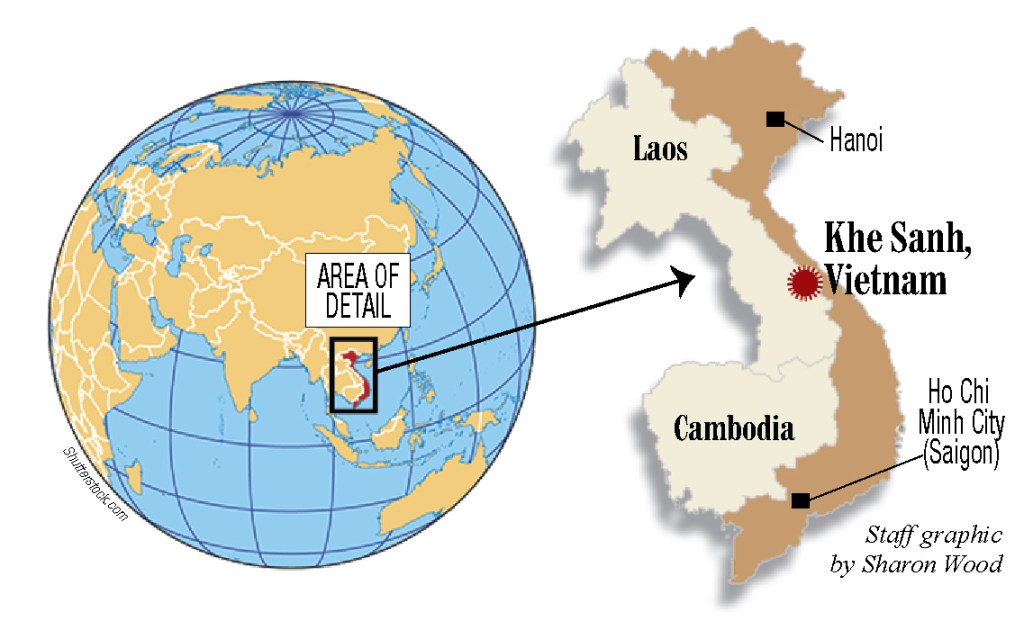

Sunday marks the 50th anniversary of the start of the siege of Khe Sanh, one of the bloodiest, longest and most controversial battles of the Vietnam War, where about 6,000 Marines and other U.S. troops were under siege for 77 days by about 30,000 of the North Vietnam Army’s most highly trained troops.

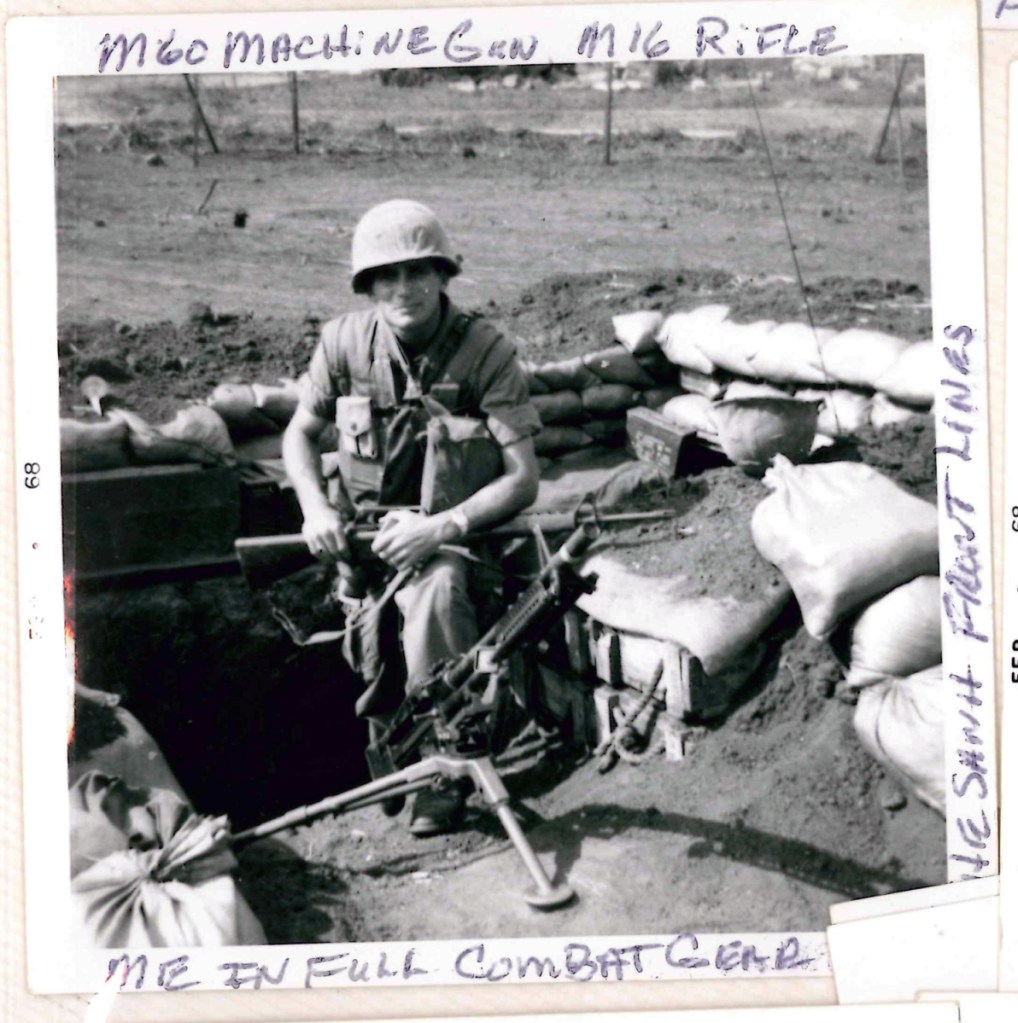

Two central Mainers who were there in the foxholes and tents of the half-mile-by-1-mile U.S. base — short on supplies and ammunition as it was hit regularly by a barrage of rocket, artillery and mortar fire — said they feel lucky to be alive. They are Sargent and Evan Plourde, 70, of West Gardiner, who was a Marine private first class, a machine gunner who carried an M60 machine gun during his time at Khe Sanh, from February 1968 until the end of the infamous siege on April 8, 1968.

“There was just somebody out there looking over me; I sure wish that happened for the guys we lost,” Plourde said in an interview this past week.

Some 8.7 million U.S. service members worldwide and an estimated 48,000 Mainers served in the Vietnam War during the period from 1964 to 1975, according to data from the Maine Bureau of Veterans’ Services. Of the total number of Mainers who served, 343 died.

Sargent recalled another incident, in which his pistol belt got stuck on the ramp on the tail of a C-130 cargo plane. He had jumped onto it to get out of Khe Sanh on emergency leave because of the death of his brother-in-law, Guy Robert Bean, who was killed in combat in Vietnam at the age of 21.

As the plane took off, Sargent was stuck on the tail, hanging there, unable to get into or off the plane until the plane’s crew chief saw him, came to his aid and helped him into the aircraft. In doing so the man, whom Sargent didn’t know, plummeted to the ground as the plane rose into the air.

Sargent said he doesn’t know if that man lived or died — something he still feels bad about.

The greatly outnumbered U.S. troops at Khe Sanh rarely engaged in direct firefights with the enemy, instead generally sticking to the base, because going out on patrol was too risky.

On Feb. 25, 1968, a patrol went outside the base with 32 men, Sargent said. Only nine came back.

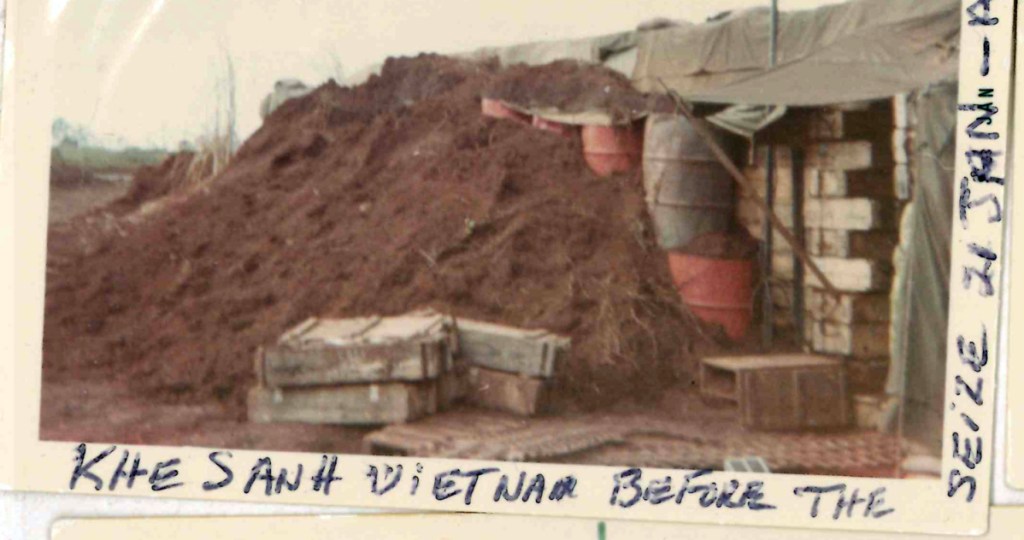

Two days earlier, the base had been blasted with 1,307 rounds of enemy mortar, rocket and artillery fire. In the month of February, Sargent said, the base was hit by 4,400 rounds of fire, which left the airstrip ripped apart and cratered, barely usable by planes, which resulted in the base being short on supplies, including, for 77 days, any food other than C-rations. Sargent said he lost 22 pounds while he was there.

Plourde said he, too, remembers the brutal shelling on Feb. 23.

“We were in our foxhole for hours,” he said. “When we came out and picked up the pieces, there were a lot of casualties.”

The plane taking Plourde into Khe Sanh had barely touched the ground when another plane, coming in after it, got hit by enemy fire.

Sargent, a gunnery sergeant in Khe Sanh, who remained in the military until he retired as sergeant major in 1976, was 33 when he was in Khe Sanh, the old man of the group made up mostly of young men in their 20s.

He recalls, painfully, the death of one of them, Wilbur Stoval, who was killed by a rocket that came into their battery command tent. That was March 9, 1968, just 13 days before he was scheduled to go home. The attack occurred when Sargent was still on emergency leave. He said if he hadn’t been on leave then, he’s sure he would have been killed in that rocket strike.

Both men said they’re worried the sacrifices their fellow troops made in Vietnam and elsewhere could be forgotten. Sargent said when he has gone to local schools, students seem to know little about the country’s military history.

He said he’s not looking for a parade. He just wants to make sure service members’ wartime sacrifices are remembered.

Plourde said students aren’t being taught enough of the country’s military history.

“It’s sad. Schools don’t really teach about it,” he said. “It’s the history of the United States, a free country. Hundreds of thousands of these guys lost their lives, over the years, protecting this country.”

The number of casualties suffered by both sides in Khe Sanh has long been disputed. The Khe Sanh Veterans Association estimates 730 Americans weere killed in action in Khe Sanh, and more than 2,500 wounded.

After the siege ended, the United States abandoned Khe Sanh in July 1968.

“We lost all those troops there, and then they just leveled it,” Sargent said, shaking his head.

Both Sargent and Plourde said they plan to attend a 50th reunion of those who served in Khe Sanh, later this year in Washington, D.C.

Keith Edwards — 621-5647

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.