AUGUSTA — More than two decades after Tracey Stevens-Wheeler had been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes, the 45-year-old thought her health care providers had made a breakthrough.

Over the years, they’ve upped her insulin, and downed it. They’ve given her pills. They’ve recommended a carbohydrate-free diet. Through it all, the Pittston woman has suffered four heart attacks related to her seesawing blood sugar levels, she said, as well as many episodes of dry mouth, disorientation and other symptoms.

Finally, about two months ago, providers at a center run by MaineGeneral Health prescribed a new drug, Tresiba, which Stevens-Wheeler injects every morning. She visits the Augusta center every couple weeks so her providers can adjust her doses.

“It really works, and I love it,” she said of the new medicine. “Since they put me on this, my sugars have gone down drastically.”

But Stevens-Wheeler’s relief was short-lived. In early February, she learned that MaineGeneral, one of the largest health care organizations in the state, was downsizing its Diabetes and Nutrition Center after losing about $500,000 per year on the program.

That change has forced Stevens-Wheeler and many other patients to look elsewhere for specialized diabetes care. She now worries about the interruption in her care and the time it could take her to travel to another hospital.

“When they told me they were getting done there, when I got that notice, I was infuriated,” Stevens-Wheeler said.

While MaineGeneral will continue to offer educational programs and some diabetes care, it is cutting several positions, including an endocrinologist and a nurse practitioner, that allowed the center to provide specialty care to patients such as Stevens-Wheeler. Diabetes is a chronic condition that, like obesity, generally has been growing across Maine and the U.S., and is one of the country’s leading causes of death.

Hospital officials say the cuts are related to declining reimbursements from Medicare and MaineCare, which have eaten into organization’s overall bottom line. Those declines, officials say, have made it hard to keep offering a service that costs $1.4 million annually, yet is losing money despite the large number of Mainers who have or could be at risk for diabetes.

“The reductions in reimbursements, at the federal and state level, it doesn’t allow us to cover the cost of this program, which loses about a half-million dollars a year,” said Chuck Hays, president and CEO of MaineGeneral. “Unfortunately, it’s a need in our community, but it’s not something we can continue to offer.”

Dora Ann Mills, the vice president for clinical affairs at the University of New England and former director of the Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention, said the challenges aren’t unique to MaineGeneral and point to a larger flaw in U.S. health care.

While health insurance and federal programs may cover adequately the costs of late-stage complications from diabetes, such as an amputation, Mills said, they provide far less support for the screening, prevention and early treatment of a chronic disease.

“It’s very problematic,” she said. “What MaineGeneral is facing is, tragically, not uncommon across country. We need to make sure diabetes and other similar diseases are addressed upstream.”

Upward of 4,000 patients receive care in the Diabetes and Nutrition Center — located in the Ballard Center on East Chestnut Street in Augusta — and could be affected by the change. Hospital officials said they didn’t know how many of those patients would be referred to other health care organizations.

In a letter to the affected patients, the hospital advised them to consult with their primary care providers about whether to stick with the reduced services or try to meet their needs at another hospital.

In a sign of how many relied on the Augusta center, hospitals in Waterville and Lewiston already have seen a rush of new patients. Maine Medical Partners in Portland also might see a bump in new patients, according to an official from that system.

On just one day last week, Inland Hospital in Waterville received more than 40 referrals from patients seeking diabetes and nutrition services, according to Dan Booth, Inland’s vice president of operations.

“Those are MaineGeneral patients only,” Booth said. “That’s been the pattern since this was announced. Those are huge (numbers).”

Jeff Hansen, of Sidney, holds instruments on Saturday he uses to monitor his blood sugar levels to control his Type I diabetes.

CARE IN FOCUS

Diabetes takes two forms. Type 1 diabetes most often develops in children and has been associated with problems in the immune system.

Far more prevalent is Type 2 diabetes, which mainly affects adults. It hinders their ability to metabolize sugar, leading to increased thirst, hunger, weight loss, fatigue and other symptoms. Risk factors include being overweight or inactive, and a having a family history of the condition. If not treated properly, it can lead to complications such as heart disease and foot damage.

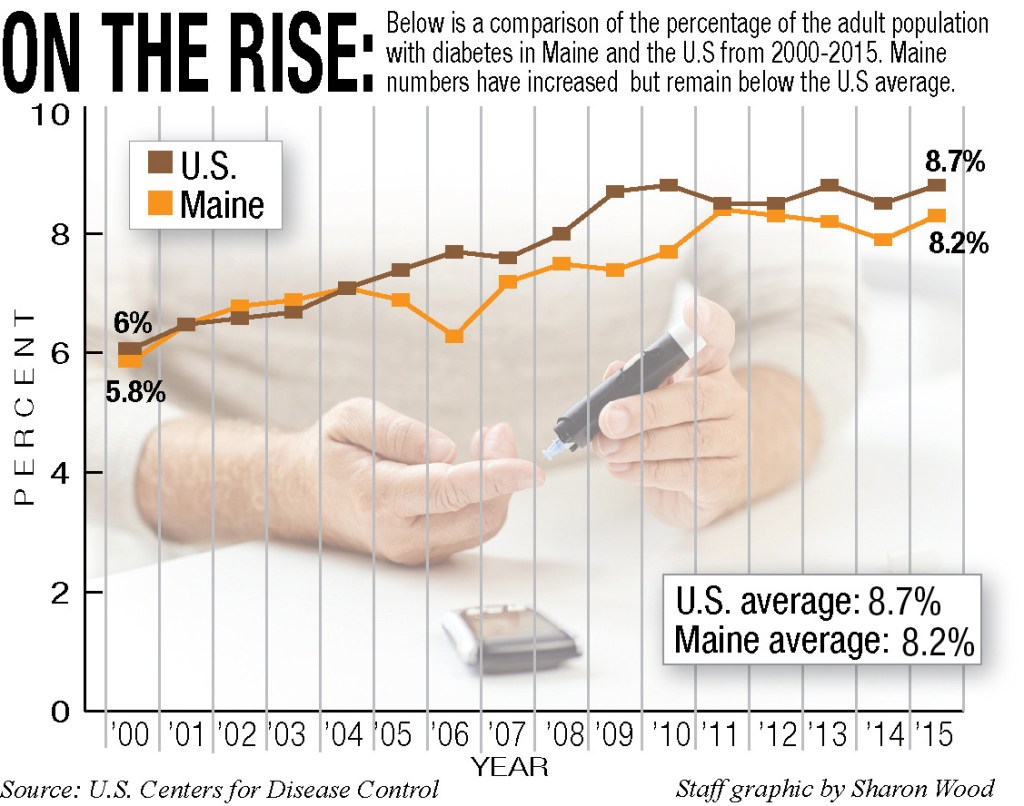

The age-adjusted rate of Maine adults with a diabetes diagnosis has remained around 8 percent over the last few years, just below the national average. That’s up considerably from the 5.8 percent who had a diagnosis in 2000, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

While simple cases of Type 2 diabetes can be managed in a primary care setting, specialists generally must treat patients with Type 1 diabetes or more complicated cases of Type 2, according to providers interviewed for this article.

Without an endocrinologist practicing at MaineGeneral anymore, Stevens-Wheeler is one of the patients seeking care at Inland Hospital in Waterville.

She’s been visiting MaineGeneral every couple weeks since starting on her new medication, and expressed frustration at the Augusta hospital’s administrators.

“The way things came about, it’s like we don’t matter to them,” she said. “I go there for help with my insulin, and they’ve helped with nutritionists too. What made me mad was the thought of them not thinking about me as a human being, as just a moneymaker. I thought MaineGeneral was a nonprofit organization.”

Another patient, Jeff Hansen, of Sidney, expressed similar concerns. After he graduated from college, Hansen received an unusual diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes after experiencing severe dehydration.

Now 54, he works as a hydrogeologist for a company in Augusta and has been going to MaineGeneral to adjust his insulin doses. Now he plans to seek care for his diabetes in Lewiston.

“I work in Augusta, so obviously driving an hour to the nearest place that will now be able to offer commensurate care is going to be an issue from a quality-of-life standpoint,” he said. “I’ve got to take time off every time to go down there, so pretty much time waiting to see doctors kills a half day.”

Like Stevens-Wheeler, Hansen questioned MaineGeneral’s decision to discontinue “a necessary service” and wondered whether the organization is thinking about trimming other programs.

A spokeswoman for MaineGeneral said in an email that “as of now we are not looking at reducing additional services,” and that “we’ve done a lot of hard work to find efficiencies across our system.”

EXTENSIVE DEMAND

In an interview, Hays, the CEO, said that even though MaineGeneral has nonprofit status, it still needs to watch its operating margins. In the last year, two credit monitoring agencies have lowered their ratings for MaineGeneral Medical Center, in part because of a $22.9 million operating loss last fiscal year.

Hays has pointed to the declining Medicare and MaineCare reimbursements as a significant challenge to the organization.

Last week he referred to a report from the Maine Hospital Association that showed half the state’s hospitals have operated at a loss in recent years and identified several external challenges to their viability, including an average reimbursement rate from MaineCare — the state’s version Medicaid — of 72 cents on the dollar.

Those rates have contributed to the losses at MaineGeneral’s Diabetes and Nutrition Center, Hays said.

Other Maine hospital officials and health care experts agreed about the challenges and expenses of offering care in a specialty such as endocrinology.

“The demand here is extensive,” said Stephen Kasabian, chief administrative officer for Maine Medical Partners, a group of practices in the Portland area that includes a larger endocrinology and diabetes center. “There are many, many, many new diagnoses of diabetes that occur in this state and across the country every single day.”

But, Kasabian continued, endocrinology is “a challenging service to deliver. There are a lot of people with the disease who are not compliant, or people who make appointments (and don’t show up). … Basically, medicine as it’s reimbursed today, it’s challenging all around. It’s the same for many specialties. It’s challenging to deliver economically. We deliver it because it’s our mission to do so.”

Other health care organizations are stepping into the vacuum generated by MaineGeneral’s decision. Kasabian emphasized that Maine Medical Partners intends to keep offering endocrinology services at its existing level, and he said the organization may receive referrals about MaineGeneral patients.

Both Central Maine Medical Center in Lewiston and Inland Hospital in Waterville already have received referrals about those patients.

After the Augusta hospital decided to cut endocrinology services, the wait for patients to see Inland’s part-time endocrinologist has grown from about two months to seven, according to Booth.

While the hospital previously had been considering hiring a full time endocrinologist, it now has accelerated those considerations. By adding another endocrinologist, it could see more patients with diabetes and other disorders, such as thyroid disease, Booth said.

But Inland, which is part of the statewide network of hospitals in Eastern Maine Healthcare Systems, has been caught off-guard.

“We’re getting a lot of calls from patients who don’t quite know where to go for their care,” Booth said. “Inland was not prepared for that change at MaineGeneral. Now we are reacting to that and trying to do it in a prudent way. We’re having an influx of patients that we’re not prepared to care for in the way we want to.”

Charles Eichacker — 621-5642

Twitter: @ceichacker

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.